Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Tech Cities of the Bible

-

Give Me a Place

-

Send Us Your Surplus

-

Masters of Our Tools

-

ChatGPT Goes to Church

-

Poem: “Blackberry Hush in Memory Lane”

-

Poem: “A Lindisfarne Cross”

-

Poem “Fingered Forgiveness”

-

God’s Grandeur: A Poetry Comic

-

Birding Can Change You

-

Disability in The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store

-

In Praise of Excess

-

A Church in Ukraine Spreads Hope in Wartime

-

Toward a Gift Economy

-

Readers Respond

-

Loving the University

-

Locals Know Best

-

A Word of Appreciation

-

Gerhard Lohfink: Champion of Community

-

When a Bruderhof Is Born

-

Peter Waldo, the First Protestant?

-

Humans Are Magnificent

-

Who Needs a Car?

-

Covering the Cover: The Good of Tech

-

Jacques Ellul, Prophet of the Tech Age

-

It’s Getting Harder to Die

-

In Defense of Human Doctors

-

The Artificial Pancreas

-

From Scrolls to Scrolling in Synagogue

-

Computers Can’t Do Math

-

The Tech of Prison Parenting

-

Will There Be an AI Apocalypse?

Taming Tech in Community

How the Bruderhof community tries to be intentional about personal technology.

By Andrew Zimmerman

June 26, 2024

Available languages: Deutsch

The basket quickly became known as the “handy garage.” (Handy is German for cellphone.) In reality it wasn’t particularly handy when none of us could turn to Google or Wikipedia to settle arguments at the dinner table. For a few days, I noticed everyone’s discomfort when a notification sounded from across the room, and we each strained our ears to discern if it had been ours. Some days at first, one of us would notice that the basket looked strangely empty and would pass it around the table again to retrieve a few forgotten phones. But soon enough, we all habitually parked them in the garage upon entering, and it did seem that conversations lasted longer and had more substance.

Here at the Gutshof, one of about twenty-five Bruderhof communities inspired by the first gathering of believers described in the Acts of the Apostles, we have no private property but share a common purse and common life. Some Bruderhofs are home to several hundred people, while others are smaller households like ours, but in all cases, we share work, meals, and worship. Members cook food, or grow the food, or wash the laundry, or mow the lawns, or work in the furniture factory – and draw no salary for doing so. At the larger communities, we operate elementary schools, middle schools, and high schools for children of members as well as neighbors. Onsite clinics provide free medical and dental primary care. Elderly members are offered ways to meaningfully participate in the work until they’re no longer able and are then cared for within the community.

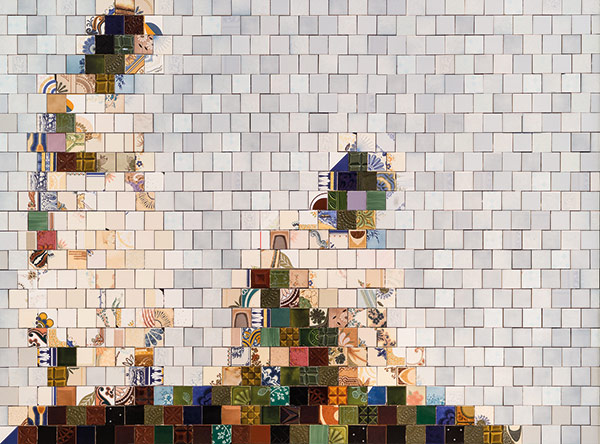

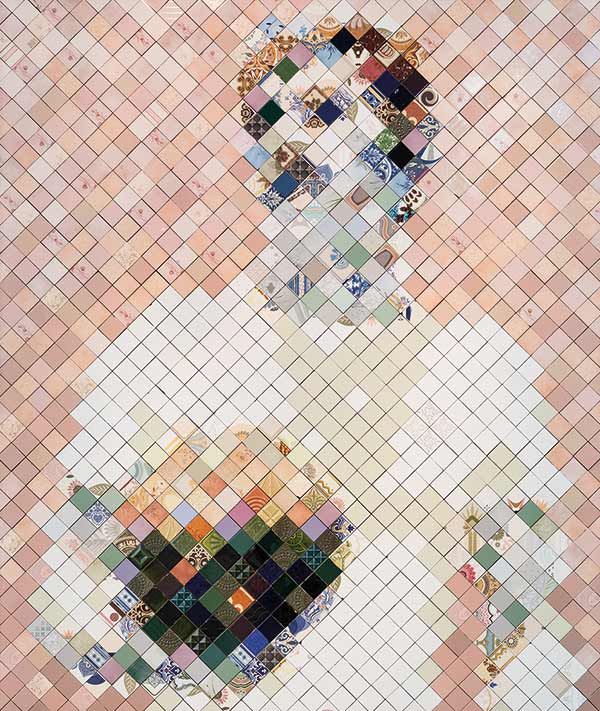

Pedrita, Untitled, reclaimed tile trims, 2018. All artwork by Pedrita Studios (Rita João and Pedro Ferreira). Used by permission.

Jesus said his disciples would be in the world, but not “of the world” (John 17). As part of our collective effort to discern what obedience to this teaching might mean today, we adopt an attitude of caution toward new technologies, just as we take a countercultural stance toward other norms of contemporary society, for instance money (we hold no private bank accounts or credit cards), career (we work where we’re asked to, not where we want), fashion (simpler is better), and sex (chastity and faithfulness in marriage).

Such caution, when directed at newer technology such as smartphones, does not necessarily mean hostility. And it’s not a blanket ban. We consider that tools, whether simple or high tech, are used to build up the community, advance our mission as a church, and help individuals and families to flourish: we have long used electricity, cars, robotic welders, automated logistics systems, and medical technology such as diabetes monitors.

Despite this openness to positive uses of technology, we’ve also drawn a number of boundaries around technology we choose not to use; these can strike newcomers as fairly strict. These guidelines aren’t moral judgments – we won’t tell you you’re a bad person if you do these things – but arise out of a communal sense that certain technologies prevent flourishing more than they help. When television came along, we chose not to have TVs in our family apartments. Members typically don’t use social media, except for business or outreach purposes (for example, to promote this publication). Our kids don’t get smartphones until they graduate high school. Having chosen a life of voluntary poverty – in the sense of having no personal spending money and wanting to live simply – most community members are little affected by the technological consumerism that looms large in society, from online advertising to gambling sites. It’s hard to make impulsive Amazon purchases when you don’t have your own money. For similar reasons, we also generally aren’t early adopters of personal tech, since we don’t choose our own devices (so no chance of picking up that latest Apple gadget unless you can make a case to your fellow members that you actually need it).

The Siren in our pockets was adversely affecting many forms of creative contribution to community and society.

Even where we welcome technology for its efficiency, we’ve learned to appreciate that it can be healthy to give it a rest now and then. We may use automatic dishwashers after a communal meal for two to three hundred people, but we’ll also fill up a large sink, surround it with four or five men, and tackle the pitchers and serving bowls. (There are memorable conversations to be had while scrubbing out pans.) Other times we’ll get out shovels and wheelbarrows for landscaping rather than using a tractor, for no other reason than that it’s good to get your hands dirty and your muscles tired while working together with others.

We thought we had a pretty grounded and effective approach – until the pandemic struck. Like many churches, we rolled out infrastructure and devices during the various lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 so church services and members’ meetings could be held online, and so that many of us could work from home. The Bruderhof’s high schools issued tablets to accommodate virtual learning. Prior to that, few residential apartments had Wi-Fi, and less than a quarter of adults had smartphones. Of course, the technology had upsides – it enabled us to keep connected, united in prayer and mutual support, through some difficult months.

But as the pandemic receded and in-person meals, meetings, and work resumed, the phones, tablets, laptops, and Wi-Fi stayed.

How much the ground shifted during those trying months only became clear a couple of years later. Within our close-knit communities, we began to notice that it seemed to be more difficult to hold conversations without interruption. Communal meals and meetings were interrupted by unsilenced phones. Work-life balance seemed out of whack in many families, with more parents working from home at odder hours. More personal technology was available to children, and families found themselves watching more movies and sports and playing fewer board games and less pitch-and-catch. Although the beginning of the pandemic had brought a renewed interest in crafts, hobbies, baking, and music, those heady DIY vibes seemed to have faded, a worrying trend in a church community that has always held practical creativity in high regard.

Pedrita, Untitled, reclaimed tile trims, 2018.

We realized that we were at risk of losing a valuable portion of the face-to-face interactions that are essential to the Bruderhof’s way of life. We were reminded that tech is not in fact neutral: It can be a passive hindrance to community by stealing our time. And it can also be an actively destructive force – not just among teenagers, but among people of any age.

This, of course, is not a problem unique to the Bruderhof. Over the past decade, research featured by writers including Jean Twenge, Nicholas Carr, Cal Newport, and most recently Jonathan Haidt has shown the grave costs of the introduction of smartphones and social media, and these costs appear to be highest for children and adolescents. Haidt’s book The Anxious Generation (March 2024) lays out starkly troubling trends: drastic increases in anxiety, depression, and suicide. “By a variety of measures and in a variety of countries, the members of Generation Z (born in and after 1996) are suffering from anxiety, depression, self-harm, and related disorders at levels higher than any other generation for which we have data,” he notes. We were simply seeing the evidence of what such authors have long argued: phones are bad for our mental and physical health. The Siren in our pockets was adversely affecting many forms of creative contribution to community and society. In addition, more members found themselves struggling with temptations to pornography and excessive gaming, which are more accessible through personal tech.

Many of us sensed that as late adopters we were actually worse than some others at setting boundaries for tech use and realized that we needed to put the brakes on.

There was broad (though not universal) consensus in our communities that the growth of personal tech had become a serious problem. According to the rule of our common life, it was up to the body of members to find a solution. One such possible solution, which some were eager for, would have been to develop strict new rules to apply to each of our communities to combat perceived misuses of technology. Since we make decisions unanimously, this would have meant members agreeing on limitations that everyone would be expected to accept and uphold.

We chose not to take this path, which would inevitably involve a degree of legalism and rigidity. It would not be in keeping with our identity as a community founded on trusting and honest relationships rather than enforced conformity. Instead, a team of pastors (including myself) and IT professionals assembled to address issues and bring forward solutions. We went in knowing we could not roll back the clock, but we were willing to see how we could become more disciplined and intentional about our use of personal technology.

We realize better today than we did two years ago that we should be too busy caring for our neighbors to spend excessive time online.

In turn, we reported to our congregations about the problems we saw and asked them too to have discussions and help come up with practical suggestions. In these meetings, rather than focusing on the “evils” of smartphones and social media, we looked for specific, achievable solutions to problems like a dearth of connection or a rise in loneliness. Members came up with guidelines for appropriate phone use in various communal settings, to reestablish some basic social norms. Our emphasis was not on controlling each other but on mutual accountability, on nurturing the positive vision of what community is for, and letting personal tech find its place within that.

The proposed guidelines, which have been adopted with varying degrees of enthusiasm, included suggestions around how and when earbuds should be worn in communal workplaces such as workshops, kitchens, or gardens so that real conversations could flourish instead of everyone listening to their podcast of choice, and the expectation that we wouldn’t check our phones during communal gatherings. And while it need not be strict, we realized we would all benefit from some form of Sabbath observance, where it’s expected you won’t answer calls, texts, or emails on Sunday.

Some things, however, were stricter: we reaffirmed our stance on not providing smartphones for kids before high school graduation, and on avoiding personal social media use. In cases where a social media app might be necessary, the users have to make their case: for example, some of our college students might need a certain app to receive their homework assignments. A sports team may arrange practice on a social media page; artists, photographers, and potters may use Instagram to showcase their work. Several community schools decided that teachers being on their phones was an issue of child safety, so they now have staff turn off their phones while teaching. By no means are we the only ones to do this. I recently visited a church in Spain where the kids’ room had a prominent sign on the door saying: “Absolutely no use of your mobile device when caring for our children!”

Pedrita, Promenade, reclaimed tile trims, 2018.

Our team also educated ourselves more fully on dangerous aspects of technology, such as the effect of social media on teens’ mental well-being, and made ourselves available as a resource to parents who might wish to have these discussions with their high-school or university-age children but feel unequipped. And for young adults, we renewed our emphasis on coaching them to learn to use tech well, since it’s inevitable that they’ll be using it. As with much of life, our attitude to personal technology requires a balancing act; like so many people these days, we are trying to find the right place for it. Our conversations and adjustments to tech use are ongoing.

We continue to ask ourselves what it means to be countercultural. From the early church on, followers of Christ have been out of step with the world; in fact, the gospel demands it. Yes, it can be hard, but maybe that’s the point. “We live amid a carnival of distractions, and we have to daily wage war on the sin in our hearts that wants to yank us away from the kingdom purposes we find in our faith,” writes Chris Martin in his excellent book The Wolf in Their Pockets. “This is why we need the community of brothers and sisters in Christ, to help us walk the narrow path when we’d rather just go our own way.”

As often as we stumble off the narrow path, we try to stumble back on again. To return to the “handy garage” experiment that emerged in my small community: as far as I know it has not been adopted by any other Bruderhof, but because it arose as a result of our discussions here, it was meaningful to us. It changed our habits enough that we were able to put the literal parking of the phones on pause, for now.

As new developments in tech continue to present new challenges, we’re committed to finding a healthy approach together. Most of us realize better today than we did two years ago that we should be too busy caring for our neighbors to spend excessive time online.

“Do not be conformed to this world,” Paul tells the Romans – and us – “but be transformed by the renewal of your mind.” The distractions of viral trends, news alerts, and targeted advertising tend to conform us to what the rest of society wants. Transforming our minds is a lot harder. And even legitimate work-related tech use can pull our focus away from our brothers and sisters, and from God. But together we can overcome this pull, and I believe we will.

About the artwork: Inspired by a set of lost (and found) photographs, Lost and Found, an art series by Pedrita, is a contemplation on the loss and recovery of our individual memories, our collective referents, and our cultural heritage.

Spanning the analog and the digital world, the past and the present, the artworks were created from discontinued industrial tiles arranged to reflect their original composition of pixels or photographic grain.

Pedrita is a Lisbon-based design studio founded in 2005 by Pedro Ferreira (b. 1978) and Rita João (b. 1978), drawing inspiration from traditional Portuguese forms and techniques.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.