Subtotal: $

Checkout-

City of Bones, City of Graces

-

Small Acts of Grace

-

In the Valley of Lemons

-

City of Clubs

-

Save Your Sympathy

-

From “In the Holy Nativity of Our Lord”

-

Digging Deeper: Issue 23

-

Beneath the Tree of Life

-

Sidewalk Ballet

-

The Eternal People

-

Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays”

-

The Pilgrim City

-

Not Just Personal

-

Editors’ Picks Issue 23

-

Madeleine Delbrêl

-

Covering the Cover: In Search of a City

-

Urban Series (Neighborhood)

-

In Search of a City

-

Readers Respond: Issue 23

-

Family and Friends: Issue 23

-

One Inch off the Ground

-

Re-Mapping Belfast

-

Serving Kings

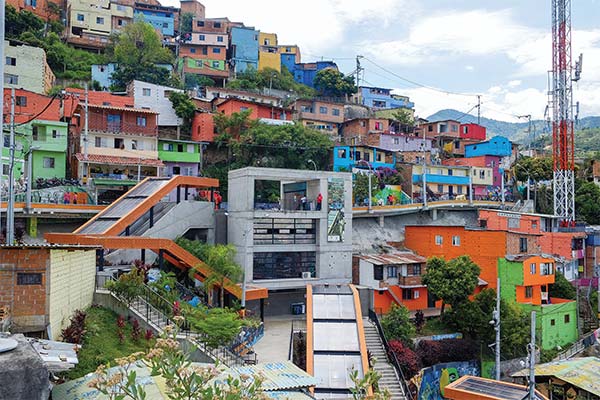

Up Hill

Through their art and stories, the residents of one Medellín neighborhood have transformed the pain of their history into a sense of place.

By Adriano Cirino

November 17, 2023

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

This article was originally published in the Winter 2020 issue of Plough Quarterly: In Search of a City.

Once it was controlled by armed groups on the fringes of the law. Then it was besieged by the army in the largest urban military operation in the history of Colombia. Today, Las Independencias, a neighborhood of fourteen thousand inhabitants in Comuna 13, the “thirteenth commune” of the city of Medellín, is a kind of open-air graffiti art gallery, accessed via a system of outdoor escalators – the only ones ever built in a slum.

Photograph used by permission from Jean-Christophe Huet

Graffiti artists are respected figures in the neighborhood. John Alexander Serna, known as “Chota,” is a local celebrity. On a February morning, he emerges from inside Graffilandia, the café-gallery constructed underneath his house, between the third and fourth flights of the escalator system. He’s immediately accosted in front of his mural Operación Orión by one of the local guides accompanying a group of tourists on a “graffitour” through the neighborhood.

“We’re lucky today!” the guide announces. “Chota is one of the most influential artists of Comuna 13.”

The gringos ask him for selfies. He obliges for a few moments, then hurries through the crowd toward the escalators, heading down the steep slope. At the bottom, another group of tourists is waiting to watch him do a live painting.

“My work used to go unnoticed,” he says. “Now, with the escalators, we’re starting to be recognized. They guarantee access to the neighborhood and allow people from around here to display their work to the foreign visitors.”

The first thing you see in Chota’s mural is a woman’s face. She is shedding a tear; green shoots grow from it. By her side, a hand throws a pair of dice onto a bunch of houses typical of the neighborhood. The first die reads “Com. 13”; the second, “16.10.2002.”

Operación Orión was painted by Comuna 13’s most prolific artist, John Alexander Serna, also know as Chota.

Photograph by Andrea

On October 16, 2002, the then-president of Colombia, Álvaro Uribe, ordered the national army to seize Comuna 13 at the request of Medellín’s mayor: a violent intervention decades in the making.

The geographically unpromising area, a very steep hill cut off from the rest of the city, saw a growing number of informal settlements constructed at the end of the 1970s. The area had no utilities and, without official status, the police left it alone. Over the next forty years, the population grew to more than one hundred and thirty thousand people. Throughout the 80s and early 90s, Comuna 13 was contested territory, primarily controlled by Pablo Escobar’s cocaine cartel, and by far-right paramilitary groups such as Death to Kidnappers (MAS). The history of the district is a bewildering tangle of alliances and antagonisms; MAS was established to protect members of the cartel and local landowners from the Marxist insurgent groups that kidnapped landowners for ransom and redistributed their land to peasants.

After Escobar’s death, the balance of power tipped in favor of the insurgents – the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the People’s Armed Command (CAP). By the turn of the millennium, it had been a generation since the state meaningfully governed the area.

The guerrillas and gangs fought continuously – over the people, over the land, and over San Juan Avenue. Running through Comuna 13, the road is the city’s access to the Caribbean coast and the smuggling that a port makes possible. Control of the Comuna is crucial to control of the drug trade.

During this period, the community lived (and died) with shootouts and stray bullets, assassinations and bombings, disappearances and extortion, and the recruitment of minors to serve as foot soldiers in these ongoing wars. During the 1990s, Medellín was known as the murder capital of the world. The violence came to a head in 2000, when right-wing paramilitary groups from the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC) also entered the dispute. The levels of crossfire were unprecedented. The killing was most concentrated in Comuna 13, with 357 homicides per 100,000 people by 2002.

And then the state launched Operation Orion. The effort involved nearly fifteen hundred uniformed men: members of the National Army’s Fourth Brigade, the Metropolitan Police, and the Special Antiterrorist Forces, as well as other bodies. Their objective: to wipe the ELN, FARC, and CAP militias off the map. The huge public force surrounded the hill and, in a coordinated action with the AUC paramilitaries, attacked at dawn. The battle lasted forty hours and ranged over six neighborhoods, including Las Independencias. Official statistics count just a few deaths, but the National Center for Historical Memory, a public body established by law in 2011, estimates that more than seventy people were killed and three hundred disappeared. There is no doubt that the government forces carried out a number of human rights violations during Operation Orion: torture, illegal detention, kidnapping.

Victims of the conflict are still looking for truth and justice for the abuses committed by the state. Operation Orion still divides opinion: the militias were eliminated and Comuna 13 was recovered, but at what cost? Some believe that the ends did not justify the means. Others see the operation as a bitter but necessary pill, a last resort that ultimately liberated the community. What is not in dispute is the pivotal nature of those two days. In Comuna 13, there is a time before Operation Orion, and a time after Operation Orion.

Afternoon popsicles with the guys

Photograph used by permission from Jeffrey Kaphan

While Chota does his painting for the tourists at the base of the hill, up at the top, where the final escalator flight connects with the Media Ladera Viaduct (a walkway) and Balcón de la 13 (a viewing point), another group applauds a performance by a group of young breakdancers. Farther along, a vendor is hawking souvenirs: “I’ve got T-shirts, caps, different styles, come take a look!”

It’s Víctor Mosquera, a businessman, rapper, and graffiti artist born and raised, like Chota, in Las Independencias. Two years ago he set up a stall on the viaduct, selling tropical fruit to the ever-increasing number of tourists. His stock has changed since then: “All of the T-shirts are personalized,” he boasts. “I design them.” He’s one of Operation Orion’s victims, hit by a stray bullet when he was fifteen. He recalls hours of torment, hidden under a bed with his family, waiting for the shooting to stop, the bullet lodged in his arm, until he was able to leave the house and get to a hospital.

“That war pushed us to write, paint, and sing our story,” he says. “And that bullet made me grip on to life much harder.”

The guerrillas were driven out – but for two more years, the right-wing paramilitaries that had helped the government carry out Operation Orion were the effective government in Comuna 13, judging and executing or “disappearing” those they deemed their enemies. In 2003, these groups surrendered, negotiating amnesty agreements; since then, the state has been in charge.

That’s the official version, though there is evidence that a paramilitary-criminal hybrid group run by Escobar’s successor, Don Berna, had a lockdown on the city for years afterward. The gangs are still a very significant presence, and in 2011 and 2012, in a bid to maintain power, gangs murdered a dozen Comuna 13 rappers who had spoken out against them. Still, the level of violence has dropped drastically: homicide levels in Medellín as a whole fell 80 percent between 1991 and 2014. The city finally started investing in the area, to repay what Sergio Fajardo, mayor from 2004 to 2007, called the city’s “historical debt” to the poor of Comuna 13, owed after years of abandonment. Fajardo’s term saw the implementation of a series of new urban development projects.

The pilot projects were based in Comunas 1 and 2. Their purpose was to build infrastructure, guided by the principles of “social urbanism,” the idea that city investment in the most cut-off and chaotic neighborhoods should seek to integrate them with the rest of the city, providing access to the city center along with better lighting and other benefits.

Completed in 2007, the projects for Comunas 1 and 2 included widening and improving roads, constructing public schools and parks, and installing a cable car. In 2006 César Augusto Hernández, a civil engineer who was then managing director of the projects, took charge of the Comuna 13 initiative and made his first visits to the community.

Many he spoke to agreed on the immediate problem: the trash. Lacking a reliable system of garbage disposal, it had piled up everywhere. Hernández had an elaborate plan involving pulleys, toboggans, and ducts to transport it to the bottom. “Once a system for trash had been designed,” one of the company’s documents states, “we also had the idea of designing something so that people could go up and down” the side of the hill.

Many of Comuna 13’s inhabitants were limited to local streets, unable to tackle the area’s steep slopes. Particularly affected were pregnant women, elderly people, and anyone else with compromised mobility, but even the fit and young were hard-pressed to make the scramble up through the tumble of houses on the hillside a part of their daily routine. Residents were also segregated from the rest of the city, cut off from its job opportunities and public services. Those who lived at the top of the hill with jobs in the city center had to hike the equivalent of twenty-eight stories up poorly maintained stairs at the end of each day.

Facing this scenario, Hernández came up with a seemingly ridiculous idea: Why not install escalators on the hillside?

In 2008, the incoming mayor, Alonso Salazar, allowed himself to be persuaded by the engineer’s arguments. “I showed him a map of the city,” Hernández recalled in an interview, “and the outlines of the escalators that would liberate the ghettos. I told him any mayor could build schools, hospitals, or parks, but that he could do something completely new: reconstruct the social fabric … give the community a project that would make them feel something they might never have felt before: pride.”

The steep hillside on which Comuna 13 sits is now accessible by a system of escalators.

Photograph by Tom Klein / Flickr

The mayor opened bids for the escalators’ installation in 2010. Accompanied by community leaders, teams of topographers, civil engineers, and architects ventured into the area on trips to assess the situation, and they came up with a plan: the system would be installed in Las Independencias, and would connect to other infrastructure – the Carrera 109 Urban Walkway, the Reversadero, Balcón de la 13, and the Media Ladera Viaduct. Together, these would form a circuit of access for the inhabitants.

“More than anything, the project was about mobility,” the architect Juan Carlos Ayure explains. “No one ever thought it would become a tourism thing.” He had worked for a private construction company contracted to help remodel the landscape and install the escalators. But before construction began, there was the question of community buy-in. More than thirty houses would have to be purchased and demolished to clear the way.

The city carried out an educational campaign: a series of huge meetings and local assemblies, designed to make residents aware of the benefits and potential risks of the new technology. Many of the neighborhood’s inhabitants were so cut off they did not even know what an escalator was.

“How could we explain to these people – people who have few resources, no luxuries, people from a very low social stratum – that there are such things as electric staircases; how do we convince them to let us install them?” asks Ayure. “We took them to places like shopping centers, to show them that there was no need to be scared, that the escalators would not eat them, or swallow them up, that they wouldn’t fall.” These campaigns were rooted in the ethos of the city’s social urbanism, which encourages citizen participation at every stage of the work.

The four-million-dollar project began in February 2011. Nearly three hundred workers were hired, the vast majority of them local. The main qualification was having no criminal background. “We went up there to begin hiring, and it was complete madness,” Ayure recalls. “The local hoodlums fought, and there were shootouts during the day” – the slang is “piñata.” “People would call me – ‘Boss, we’ve got a piñata!’ We had to get a siren. We told the workers: ‘Listen guys, when you hear the siren, throw everything onto the floor and run home.’”

Amid these interruptions, the crew widened and paved walkways, repositioned aqueducts and sewage systems, shifted electrical networks, constructed two new public buildings, created green areas, and raised containment walls. Then, at last, came the installation of the escalators.

Three artists collaborated to create this Comuna 13 mural.

Photograph by Andrea

One of the more Herculean challenges involved transporting the system up the hill: six double flights of escalators, each between eight and fourteen tons. And then there were more subtle difficulties: “We came here with a preliminary final design,” says Ayure, “but in a slum like this, a new shack or a new alleyway pops up every week. So my work consisted in finding solutions, once the work was already underway, for all these questions that look so pretty on paper but which in real life are something else entirely.”

On December 25, 2011, ten months after the work began, the citizens of Las Independencias inaugurated their escalators. Simultaneously, the city invited neighborhood artists to do graffiti on the façades of nearby houses. The atmosphere was celebratory, and not only because it was Christmas. In a real way, these escalators set the citizens free.

Medellín was named “the most innovative city in the world” in 2013, in a contest promoted by Citigroup, the Wall Street Journal, and the Urban Land Institute. Since then, tourism has exploded. Visitors come from all over the world, now drawn to something beyond the narco-tourism and sex tourism that still persist. The new attraction is Comuna 13, and the transformative possibilities of social urbanism. According to government data, the Comuna 13 escalators received approximately one hundred and seventy thousand tourists in 2018, 70 percent of them foreigners. And the trend is upward: January 2019 saw close to forty thousand visitors.

This has, of course, changed the neighborhood. The universal problem of gentrification exists here too: while some residents are celebrating the increased value of their homes, others complain about the hike in prices and the cost of living.

Today Las Independencias is a community in which the local and the cosmopolitan cut across each other, collide, and fuse. Consider the foreign lingo that lends names to local attractions, artistic groups, and establishments: Graffitour, Black & White, Coffee Shop Com. 13. In this neighborhood, walls once studded with bullets are transformed by artists’ hands into illuminated manuscripts: the pages of their own recent history, aglow with beauty and memory. The houses, in their turn, shelter a greater and greater variety of businesses – barber shops, grocery stores, clothing and souvenir shops, bars, and galleries.

The escalator system runs for sixteen hours daily, and is operated by a public company. On a February morning, between the second and third flights, Juan Carlos Zapata Holguín, clad in a yellow jumpsuit and black wellingtons, is clasping a pressure cleaner. “Today we’re cleaning the escalators and the communal zones,” he says. He’s one of the fifteen “educational managers,” the operators of the escalators who keep them clean and running. He works carefully, occasionally interrupting the stream of water to let people past as they go up and down in a ceaseless flow.

At one point, he darts to the end of the second flight and keeps a woman from tripping. “They look harmless, but these stairs are dangerous,” he says. His primary job is to ensure the safety of the users, and to assist those who need it.

The tourists, too, are themselves a kind of hazard. The lack of privacy can be annoying: “Tourists come up to take photos; the view’s blocked by the residents’ clothes hanging to dry!” Holguín observes. “Or locals go out in the morning wearing pajamas to buy bread for breakfast, and it’s embarrassing … because suddenly there’s a tourist taking photos. … They complain, but they like it: business is good.”

A breakdancer performs on the sidewalk.

Photograph used by permission from Wesley Tomaselli

His colleague, David Andres Zapata, grew up when the neighborhood was under the rule of the guerrillas and the paramilitaries, and witnessed Operation Orion as a child. Before getting the job looking out for the maintenance and safety of the escalators, he helped to install them. For him, the changes that the escalators have brought have been positive. He does not feel invaded, despite the large numbers of tourists: “For many communities, this would be stressful: ‘Why can’t I walk through my neighborhood?’ they would think. But,” he claims, “not in Las Independencias. Not here.”

Through their art, through the stories they tell each other and those who visit, the pain of their history is transformed into a sense of place. The citizens of Comuna 13 know what they have suffered, they know what they have survived, and they know who they are.

Translated by Rahul Bery

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

G Scott Mikalauskis

'(Victor Mosquera) recalls hours of torment, hidden under a bed with his family, waiting for the shooting to stop, the bullet lodged in his arm, until he was able to leave the house and get to a hospital. “That war pushed us to write, paint, and sing our story,” he says. “And that bullet made me grip on to life much harder.” ' Can we get more about this guy? Imagine an article that tells the story of Medellin through the life story of this graffiti artist. That would be an amazing article-- or an amazing novel. Somebody please go write it, so that I can pay money to read it. Please. Thank you.