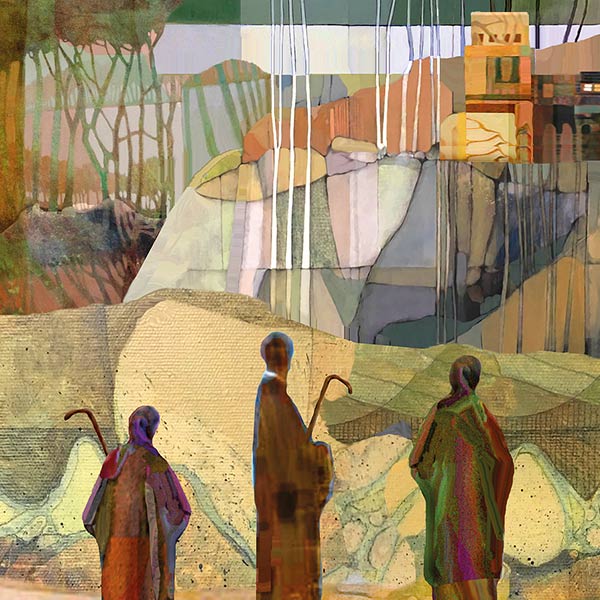

I live next to a church in Bethlehem, just a ten-minute walk from where Jesus was born. Our church is built of Bethlehem stone – a pale pink that catches light in the morning and in the evening. It stands on the side of a hill, with a great, vast view onto the hills looking in the direction of Jerusalem. In the morning, when I wake up to get the children off to school, we look out the window to see the sun rising. There in the distance is the place where they say Ruth gleaned from the fields. There is the place where the shepherds saw angels, singing. If I walk up, straight behind the house, I arrive at the street called Star, where they say the three kings followed the light to arrive at the manger.

I live next to the church because my husband is the parish priest of the St. Joseph’s Syriac Catholic Church, a small community of local Christians. We are only around twenty-five families in Bethlehem, and the Mass is said in Arabic and Aramaic. On a good Sunday, fifteen people might fill the pews. On a surprising Sunday, twenty-five might make their way there. There are so many deacons and subdeacons and children dressed up in white gowns to serve that there are often more people around the altar than in the pews. The smallness has taught me that it doesn’t really matter if two people or twenty-five show up to Mass, because the bread is broken and shared all the same. There is a logic to the gospels that is not ours, one of mustard seeds and yeast, that it takes time to enter into and understand.

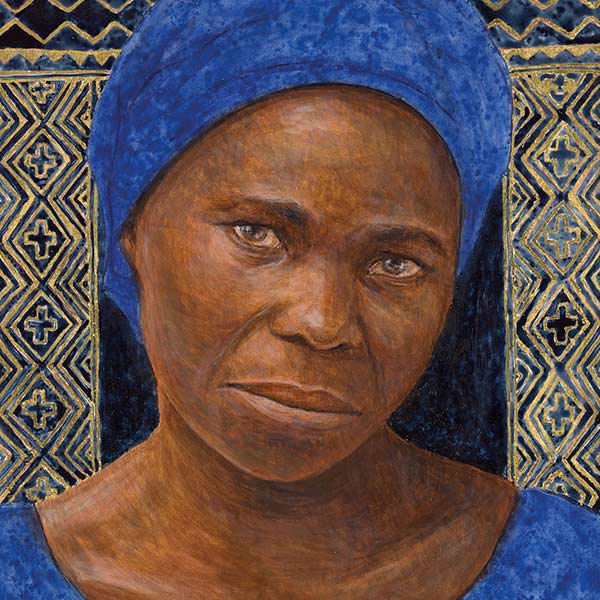

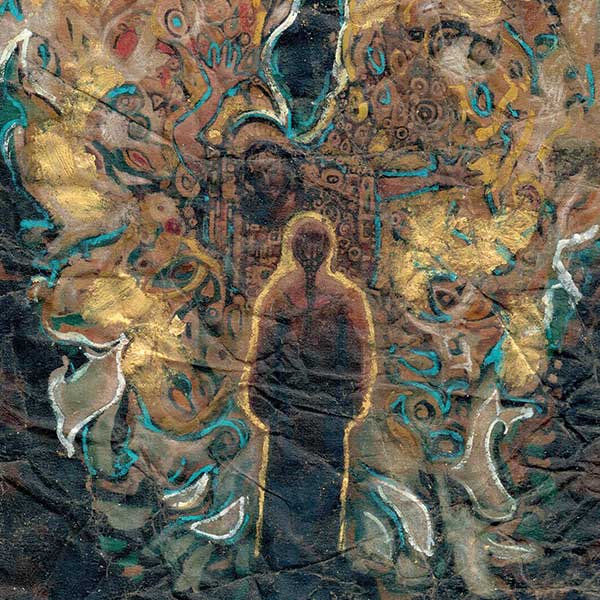

The church of Deir Maryam Al-Adrah in Iraq became a home, school, and laundromat for

displaced families. All photographs by Cécile Massie. Used by permission.

I was raised in the Roman Catholic Church, and the Syriac Church is new to me, something I am growing into. So is being the wife of a Catholic priest. It is both a privilege and simply the stuff of life – cups of coffee and cookies after Mass, my daughter’s first communion, the smell of incense on our clothes after Sunday morning. During my husband’s ordination, my daughter sat on my lap and tugged at my collar.

“Mommy, Mommy!” she whispered. “I have a tooth that’s wiggling!”

“Sweetie, your father is becoming a priest right now,” I whispered back.

She grabbed my collar more tightly and slightly raised her voice. “But this is more important!” she insisted.

There was something honest in her answer. Ordinations and teeth wiggling; God in all of it.

After my husband was ordained, the first thing we did was teach the children how to say the Our Father in Aramaic, so they might know that they belong in that moment of moments – when the faithful of the church still pray together in the language of Jesus during the Mass. My eight-year-old daughter can sing that loudly, and in our voices we feel ourselves participating in a chain of history. I have become used to being called khouriye not only by the parishioners but by everyone of all faiths in Bethlehem – khouriye being the Arabic title for the wife of a priest, in fact simply the feminine of khoury, meaning priest. I am always touched by the kindness and affection with which people say it. I was never expecting that – the way in which it touches me to be called by that name.

On Christmas Eve, when the great Mass in Manger Square is held in the Church of the Nativity, attended by hundreds and televised all over the world, we hold our small Mass at St. Joseph’s Syriac Catholic Church. We light a bonfire in the courtyard, and all of us circle around it, welcoming the light of the world coming into the darkness.

On Good Friday, when throngs walk through the streets of Jerusalem on the Way of the Cross, many in our congregation do not have permits to cross the checkpoint. We hold a tiny procession in the courtyard in Bethlehem, and Jesus is removed from the cross, placed in a casket, and processed around the courtyard. He is buried beneath the altar, and we line up and place flowers on the tomb. I now feel the importance of feeling the stone against my hands.

Three days later, on Easter Sunday, Christ is risen.

When visitors first attend our Mass in Bethlehem and hear the prayers in Syriac, they often assume that the community has always been there. Yet the members of our church are descendants of Syriac Catholics from what is present-day Turkey, from the areas around Mardin and Tur Abdin, who were forced to flee during the genocide of 1915 that they call the Seyfo, and that also devastated the Armenian community and other Christians of that region. Thousands of Syriac-speaking Christians escaped, forming diaspora communities in Aleppo and Beirut, Jerusalem and Bethlehem. By the 1920s in Bethlehem, after praying together in the caves beneath the Church of the Nativity, it was clear that all of these people needed their own place to pray. And so they built a church, with its pale Bethlehem stone and Arabic inscription in calligraphy over the entrance, the image of Saint Thérèse running toward Jesus carved into the altar. The Syrian Orthodox Christians, who had escaped a genocide with them, worshipped ten minutes away in their own church, near the steps of the fruit and vegetable market. Tied by history and tragedy, by liturgy and understanding, by the language of the past, the two communities remain close. Though if I’m honest, it’s not only these two communities. Bethlehem really is a little town, and everyone is close.

The monastery was divided with curtains to accommodate five families.

Over one hundred years have passed since those families arrived. Long ago, the members of our church stopped speaking Syriac as their daily language, and when they read it now, it is in prayers transliterated into Arabic letters. Many others from the church left or were forced to leave Bethlehem and Jerusalem in the wake of the wars of 1948 and 1967, until a few families remained to pray in the large stone church. Yet they still come to that church on the hill, a church that binds them to their parents and grandparents and great-grandparents, a church that deeply matters, in ways I do not pretend to try to name or understand, but that I have come to trust.

A few months ago, I attended Mass on a Sunday morning in Sydney, Australia. If I don’t remember the name of the church where we prayed, it is because it is of no consequence – the church was simply rented for a Sunday afternoon. There, I gathered with my friend Hana and her family, among hundreds of Syriac Catholics who had escaped Qaraqosh in Iraq in 2014 when ISIS invaded, forcing nearly the entire town to flee. As most of the town’s residents scattered across the globe, thousands found their way to Jordan, and from there applied for visas to be resettled in Australia, waiting and worshipping in borrowed churches. They still spoke a dialect of Aramaic, or Syriac, as their native language, as the language of groceries and gardening and falling in love, and they had carried that language with them when they arrived in Australia. Some eight hundred families resettled in Sydney, and a similar number in Melbourne.

I have written about Qaraqosh before, about how shocking it was to see an entire world uprooted. I watched musicians and teachers, mothers and fathers and grandparents leave, part of a story in which some 80 percent of the Christians of Iraq have escaped the country since 2003. I, like others, wrote that the Christians are disappearing from the Middle East.

Yet that Sunday morning in Sydney, so many Christians were crowded into that Syriac Catholic Mass that people were left standing in the back. It was so much larger than the twenty-five families of our little church in Bethlehem.

The priest was from Qaraqosh. The congregants were from Qaraqosh. Young boys went up to recite the prayers of the faithful, speaking English with perfect Australian accents.

The Christians of the Middle East weren’t disappearing. They were moving, starting over, still linked to the past. I realized the violence of a vocabulary that suggested that the moment they left, they no longer existed. The Syriac Catholic community of Qaraqosh had no physical church yet in Sydney, and so they rented a church from the Roman Catholics, and they drove from all corners of their new city to be there, coming together, as they always had, to pray – speaking Aramaic with one another and drinking coffee.

The church was the deepest home. The church was the home that you carry with you – the home that can’t be taken, the body, merged together again.

That same day, as I prayed with the Syriac Catholics in a rented church in Sydney, another ceremony was taking place on the other side of the world. In Mosul, Iraq, the Mar Touma Church, vandalized by ISIS during their occupation of the city, was being inaugurated after years of restoration. I studied the photographs in the newspaper, of the stone walls, the chandeliers, the illuminated icons. I knew that it meant something to have that church still standing in Mosul, even if very few Christians remained in the city.

Still, I couldn’t help but wonder what it meant – that eight hundred families were without a church in Sydney, and that a church in Mosul should be restored though almost no Christians remained to pray in it. In the end, I knew that it was wrong to measure one against the other, that both were true, both were intimately tied, both were the same church, and both were essential. They need one another. I was the one separating them. No, the church in Bethlehem with its fifteen people and the church in Mosul with very few people left and the rented church in Sydney full of hundreds of people are the same church, none more or less important, or more or less alive, than the others. It is taking me time to understand.

When I was asked to write on the theme of rebuilding churches, I immediately thought of the story of Saint Francis of Assisi, who famously heard Jesus speaking to him from the cross in San Damiano, saying: “Rebuild my church.” He set about making repairs to the physical structure of the church, until in time he understood that this is not what “church” means.

A church is exiled, and finds its way to Bethlehem. A church is exiled, and finds its way to Australia.

A church, in its deepest form, can never truly be exiled. It is always.

Somehow, in losing the physical structure of the church, we discover what church really is. We remember.

Every morning I awaken to church bells. Sometimes, after I get the children off to school, I climb the stairs and sit in the church, just to be in the quiet, all alone, and I can feel myself centered and rooted in those who prayed there before me. That feeling, of being bound in prayer across time – that, too, is church. It is connection. It is memory. It is wholeness in the face of everything.

When I remember, I try to root myself in all of the members of the Syriac Church, scattered around the world, remembering that we are one community. I could never have imagined that I would one day belong in a church in which so many of the faithful would become refugees. I did not expect that members of my community would be kidnapped during war. I did not expect that some of the priests of my church might disappear in the violence, never to be found again. I did not expect to be placed daily in the proximity of such suffering: to be thinking of those who remain in Iraq, those who remain in Syria, those suffering through economic crisis in Lebanon, those praying with me in Bethlehem despite the occupation, those waiting for visas in Jordan, those struggling to start new lives after being resettled all over the world.

Three years into their stay, Qaraqosh Christians light candles in the monastery.

We are one body, and the challenges we live with are in many ways not special but shared by people of different faiths in the Middle East in a collective tragedy in which few have been spared, in which many have lost their lives and many millions more have become refugees. I have learned that we must find a way to acknowledge the particular suffering in our communities while never letting it set us apart from the wider communities in which we live. The church should always be the door into a larger belonging – that of humanity, in which all of us suffer and struggle together, and all of us seek to witness and alleviate one another’s wounds. The church should not set us apart. The church should help us, always, to enter in. That is what my neighbors, in their goodness, have taught me.

“Write about how difficult it is for the older generation to learn English in Australia,” an older Syriac Catholic man there said to me.

“Write about how we owned a house in Qaraqosh, and how we will never be able to afford a home in Australia,” he added.

“Or about how I was a teacher back home, how I had a job that brought me dignity and respect,” a woman added. “And now I have only a simple job.”

“Write about how we did this for our children.”

“About how we are now separated from our parents and siblings, spread all over the world.”

I said I would write some of that.

After I finished writing this piece, horror caused me to return to it again. On September 26, I woke up to find my phone filled with messages. A fire had broken out in a wedding hall in Qaraqosh, killing more than one hundred people, wounding hundreds more. For such a small town, it was a tragedy beyond imagining. Everyone knew someone in that fire. For our Syriac Catholic church in Bethlehem, it was a devastating loss in the family.

A bride and groom, dancing, cheek against cheek. A ceiling catching fire. The groom looking up, as though dreaming. A world collapsing.

Just about everyone who attended that wedding had escaped from ISIS in 2014, lived in exile for two years, and then returned to try to start over, even in the face of great political instability and uncertainty.

For days, my phone filled up with more and more photos of the dead. Women and children. The bride’s family. Funeral processions with so many people it looked like the sea.

The groom, who survived with his bride, said in an interview with Sky News: “That’s it, we can’t live here anymore. We can’t live here anymore. Every time we try to have some happiness, something tragic happens to us and destroys the happiness.”

I write this from Bethlehem, where, three weeks after the fire in Qaraqosh, we are now in a war. Thousands are already dead, on both sides.

Yesterday we gathered in the stone church to pray. We said the Our Father in Aramaic. We sang a prayer to Mary carried out of the Seyfo. We lit candles.

I packed our bags, just in case.

The church has already been restored and the church is still breaking, and both of these things are true. I do not know how we will live with so much grief. Only God knows that. But we will live with so much grief. We will live with so much joy. We will live – in Mosul and Baghdad and Qaraqosh and Sydney, in Beirut and Bethlehem and Montreal and Aleppo, wherever two or three are gathered, and regathered, we will live. This church which is resurrected, which keeps starting over, still speaking the same prayer that has bound us since the beginning.

About the photography: On August 7, 2014, more than thirty families from Qaraqosh, fleeing the advance of ISIS, were welcomed by the monastery of Maryam Al-Adrah, in the town of Sulaymaniyah, Iraq. At the time, the monastery had six rooms. The families were installed in the library and the church. Several neighboring houses were also rented to accommodate them. Over the months, life became organized, Kurdish and English classes were set up, and the monastery became the living space for these approximately 150 people. Read the full story here.