Who could guess that one of life’s most piercing discoveries would be a kind of edgeless entropy, this feeling – or is it a lack of feeling? – slowly creeping into all the crannies of your consciousness, a kind of claustrophobic panic that neither the events of your life, nor the people therein, nor the whole “million-petaled flower of being here” have added up to anything at all? What is the final revelation that life grants you? That there will be no final revelation.

There is no steady unretracing progress in this life; we do not advance through fixed gradations, and at the last one pause: – through infancy’s unconscious spell, boyhood’s thoughtless faith, adolescence’s doubt (the common doom), then scepticism, then disbelief, resting at last in manhood’s pondering repose of If. But once gone through, we trace the round again; and are infants, boys, and men, and Ifs eternally.

—Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

Fair enough. A clear-eyed acknowledgment of this seems to me both bracing and necessary. And insufficient. The revelation we want – or at any rate the revelation we need – is not ultimate, but intimate. There is no culmination that a life is heading toward, no blaze of radiance of which all our itchy intuitions and perishable epiphanies have been but sparks. Revelations there are, though. Those intuitions and epiphanies are real, and our reactions to them can be, in the moment, so total and unselfconscious that they warrant the name of – if they need a name at all – faith. But they fade, those moments, and we relapse into the vertiginous Ifs we are. What one wants as one grows older is some assurance that between the endless errands that crush the soul and the sudden warbler that ignites it, between the bills and births and meals and funerals, all the graces and losses of any life attended to no matter how erratically or imperfectly – under it all there must exist some intact tissue of meaning. Not meaning such as one might fully articulate or grasp, but a deep instinctive sense, an assurance, that in the “incorrigibly plural” swirl of life there abides some singularity of being, however fleeting its presence:

SNOW

The room was suddenly rich and the great bay-window was

Spawning snow and pink roses against it

Soundlessly collateral and incompatible:

World is suddener than we fancy it.

World is crazier and more of it than we think,

Incorrigibly plural. I peel and portion

A tangerine and spit the pips and feel

The drunkenness of things being various.

And the fire flames with a bubbling sound for world

Is more spiteful and gay than one supposes—

On the tongue on the eyes on the ears in the palms of one’s hands—

There is more than glass between the snow and the huge roses.

—Louis MacNeice

This poem is balanced between reception and perception, between the sensory epiphanies out of which any sense of existential unity emerges and the formulations of reality made by the mind. These latter perceptions are not detached from reality – the poet is, like any responsible philosopher or theologian, in it up to his eyeballs – but they are secondary. I take the “more than” of the last line to be a reference to consciousness, which both connects us to, and separates us from, reality. To say that there is more than glass between the snow (chaos) and the huge roses (artificially created and sustained, an image of human beauty) is both to celebrate and lament an instant when this seemed not to be the case.

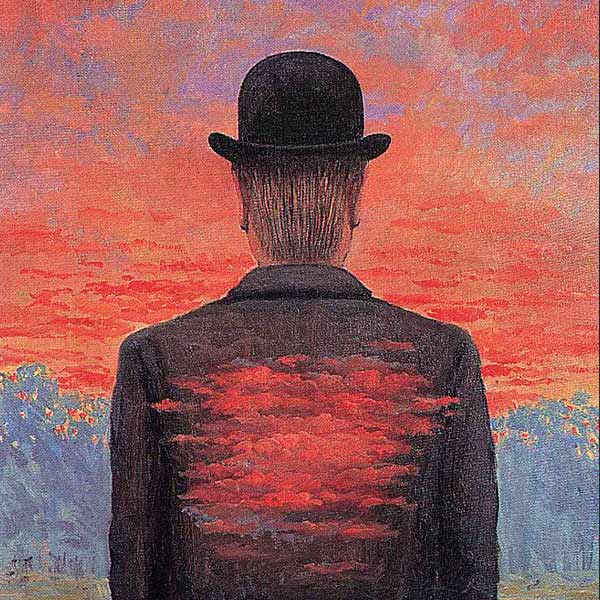

Jonah Calinawan, Dark Night, cyanotype on paper, 2020. All artwork used by permission of Dale Needham.

It’s the form of art that enables perception here. The perception is of chaos, at least from any singular human perspective, an existence so various that the human mind will never master it (there is more than glass or consciousness between the snow and the huge roses). And yet that incorrigible plural has been, if not mastered, at least entered; if not understood, at least undergone. And one’s vision has changed: the poem becomes a lens through which we see all that we are unable to see. An acknowledgment of this revelation and this limitation is the basis of – the ground for – faith. I wouldn’t necessarily say that a denial of this vision and its implications is a denial of God. (The word “God,” too, can be both accomplishment and failure, but is only sometimes, the rarest times, what it really ought to be, a beautiful fusion of both.) What I would say, though, is that a denial of this transcendent vision is a denial of reality itself. And since any individual life is part of that reality, as chaotically atomic as snow and roses, why should it be a surprise that we are Ifs eternally? A single tangerine (“I spit the pips”) is enough to inspire – and then to defeat – a philosophy of life.

Let me not have a life to look at, the way we look

at a life we build to look at, in the world belief

gives us to understand, a snowman life.

—William Bronk, “On Credo Ut Intelligam”

The thing about Christians, says the philosopher Alain, is that looking them in the eyes one senses that they don’t believe it. This is, in my experience and apart from the obviously insane, often accurate. But so is the reverse: look deep in the eyes of the avid atheist and you sense a quiver in the iron cage of conviction, a tiny – but ineradicable – If.

Terrence Malick’s film The Tree of Life attempts to give a picture of wholeness that counters the modern sense of absolute atomization and – because of that sense – anomie. Thus the movement in that film from scenes of ordinary domestic life to cosmic creation, from a howling baby to a hungry dinosaur, from the startling, stabbing particularity of childhood to the soft gauze of a not-quite-credible heaven. This effort toward cumulative vision is conspicuous in the film, perhaps too much so at times, but what is most memorable about Tree of Life in the end is not its unified vision, but the intuition it enables (and it must remain an intuition) that all of life and creation might inhere, and cohere, within an instant – and that the instant is, so to speak, imperishable; it remains not simply accessible to memory but viscerally available. Memory, trauma experts tell us, is a matter of nerves. Trauma can, some studies suggest, leave its mark on our DNA, and its effects can survive not only our accidental unconsciousness and willful oblivion, but even our physical deaths. The sins of the fathers, it turns out, are quite literally visited upon the children, whose cells retain traces of traumas that never happened to them. (The studies that address this transmission all seem to focus on negative experience, but must we assume that our moments of extreme joy do not echo in the gleeful shrieks of our children’s children?) It’s not the wholeness of scale or scope one feels in the wake of Malick’s movie, but the wholeness of these minute and immense, these joyful and terrifying, these discrete and seamless scraps of reality. In the long middle sections of the film set in central Texas, it’s as if time were tangible, as if childhood were a substance you could touch and taste and – herein lies the film’s greatness – never lose.

Never lose? Most people believe that one of the reliefs (facile distortions, the atheist would say) that religion promises is just the kind of panoptic vision I’ve been talking about. Religion is the very thing that puts all of our experiences in context; it makes life mean. But in fact this is just what faith ought to free a person from: the need for this kind of seeing, the compulsion to believe that truth is reductive. This is in fact the stale hell of modern scientific materialism, which is by no means confined to science.

In all the thoughts, feelings, and ideas which I form about anything, there is wanting the something universal which could bind all these together in one whole. Each feeling and each thought lives detached in me, and in all my opinions about science, the theater, literature, and my pupils, and in all the little pictures which my imagination paints, not even the most cunning analyst will discover what is called the general idea, or the god of the living man. And if this is not there, then nothing is there. In poverty such as this, a serious infirmity, fear of death, influence of circumstances and people would have been enough to overthrow and shatter all that I formerly considered as my conception of the world, and all wherein I saw the meaning and joy of my life.

—Anton Chekhov, “A Boring Story,” trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

What Chekhov is saying (through his character Nikolai Stepanovich, though the identification seems pretty seamless) is that, for the person who believes we are completely reducible to physiological firings in the brain, and that we are essentially pinnacle insects, impressive, yes, prone to deviations both endearing and alarming, most definitely, but in the end as rote and reactionary as the immense machine through which we move and live and have our algebraic being – for such a person, any setback to the steady pleasure of a prosperous and emotionally gratifying existence, much less any real tragedy such as the prospect of our own deaths or the death of someone we “love” (for a scientific materialist, the word must always be in quotes) blows open the doors of deliberate ignorance behind which we were hiding: the real meaning of our lives comes flooding in, which, for the materialist, is that there is no real meaning to our lives whatsoever.

Jonah Calinawan, Shouldering Sky, cyanotype print with digital drawing, 2011.

The contemporary reaction to this state of affairs is mostly either willful obliviousness, frenetic activity, or despair. (And of course these may be inseparable from each other.) Chekhov’s reaction, according to Lev Shestov, was the only possible honorable reaction available to an artist who has committed himself to “creation out of the void”:

But how shall a man struggle with materialism? And can it be overcome? Perhaps Chekhov’s method may seem strange to my reader, nevertheless it is clear that he came to the conclusion that there was only one way to struggle, to which the prophets of old turned themselves: to beat one’s head against the wall.

—Penultimate Words and Other Essays

This frustrated energy is what I feel in every single Chekhov story or play (Alice Munro is a modern inheritor), the implacability of a force that is both stronger and weaker than fate: stronger, because it doesn’t offer any kind of coherent act or agency either to align oneself with or to resist; weaker, because for anyone who actually lives out the consequences of one’s belief, it elicits not awe but entropy, not rage but resignation.

Shestov’s comparison with the prophets is misguided, I think, though it’s accidentally illuminating. The wall Chekhov beat his head against was existential – essentially the Void. The wall the prophets beat their heads against was humanity. God was a given, his existence so woven into their own that they could speak with his voice. “It is not a world devoid of meaning that evokes the prophet’s consternation,” writes Abraham Joshua Heschel, “but a world deaf to meaning.” What Chekhov sought, in the passage above and elsewhere, was respite, some solid ground on which to stand and survey the whole of life. It is, essentially, a desire to step outside of time, which, as Heschel says, is “devoid of poise.”1 For the prophetic imagination, though, there is no “outside,” and the meaning of time will never be realized by denying or evading its nature. To understand this dynamic, and one’s place in it, is not to “understand” God, but it can enable (Heschel again) “moments in which the mind peels off, as it were, its not-knowing. Thought is like touch, comprehending by being comprehended.” It doesn’t matter that you believe in such connections; what matters is that you apprehend them. And live up to them. Such moments, and the subsequent allegiance to them that sometimes goes by the name of faith, can free one from the circular despair articulated by Melville and Chekhov.

Why am I making so much of this one comparison? Because I feel that I – and many others – might be indicted by it. My instinct is to hold up something like that Louis MacNeice poem above as one of these moments when the mind peels off its not-knowing. Yet there is a sense in which the poem, for all its attestations of multiplicity and chaos, operates from within a position of (factitious) poise, or a position in which poise is at least a possibility. The lyric instant, the form that makes the perception possible, implicitly asserts an order that the poem explicitly denies. “Snow” is a deeply spiritual poem (whatever MacNeice “believed”). One feels currents of reality usually imperceptible to us rippling through the wrought iron of its lines. But the poem is not prophetic in Heschel’s sense. It takes the relationship between spirit and matter as a good, but not as a given.

Perhaps the very need to perceive some overarching meaning to one’s life is simply one more compulsion for control, not a sign of spiritual health but of pathology, the same need to control that has decimated nature, volatilized every racial and gender relation, and locked God into holy books and human institutions. I suspect the very way I have framed this entire issue – the moment versus the flux, the sensation versus the formulation, the bright particular versus the incorrigibly plural – is itself too mired in a literary and intellectual history to admit of – much less enable – other options.

I do not want a poem

that depends on madness alone

for its vision, nor on madness

alone for its madness.

Having made my meaning,

I make my meaning

clear. It is unreal

like the wings of ants.

—Ralph Dickey, “The Arcanum Poems”

Teasing out the difference between madness and vision can be a difficult enterprise for poets. And for prophets. And for anyone who has experienced – and lived to doubt – the presence of God.

Dickey’s poem is a statement about the moment of madness or vision rather than the thing itself. It’s the equivalent of criticism, or theology, or any ex post facto attempt at understanding revelation. And yet there it sits, looking for all the world like a poem, and with a glinting gem of obliquity at its heart which itself cries out for critical explanation. If you’ve made your meaning, why the need to make it clear? Oh, and: unreal / like the wings of ants?

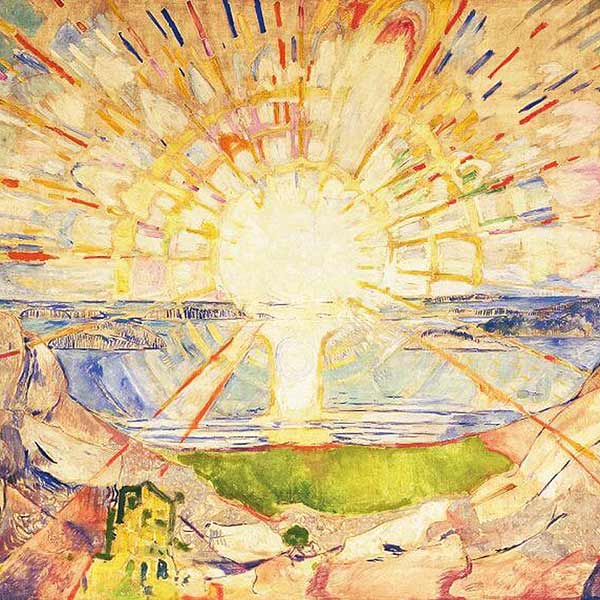

Jonah Calinawan, Three Suns, toned cyanotype print, 2011.

In fact, some species of ants do have wings, though they appear only during the reproductive stage when an ant is seeking a mate. I feel sure Dickey was in possession of this knowledge. Might his poem be saying, then (and I do think it’s the poem speaking, not the poet’s idea encoded within it), that meaning is real only when it is reproduced – only, that is, when it makes its way from one mind to another? “How little and how impotent a piece of the world is any man alone?” asks John Donne. When I think of the consciousness that generates the circular sorrow of “Ifs eternally,” or the one trying to find the one thing that will unify all the disparate experiences of one life, I think of a man – almost always a man, though there are notable exceptions – sitting alone in a room and doggedly trying to figure it all out. I read Dickey’s poem as a way out of that. It is two minds that make meaning, which is an action, not a fact, or is at least catalyzed by relation, however rooted it may be in one brain. “For where two or three are gathered together in my name,” Jesus promised, “there am I in the midst of them.” A poem is a place where two or three can gather, and a place where revelation and explanation are not separate from each other.

Ralph Dickey died of suicide at the age of twenty-eight. A poem may be a locus for spiritual connection and comfort, but it’s not sufficient. Let us not pretend time is not howling outside, even now, nor that the walls we make, even these, will long withstand it.

Can there ever be reconcilement between the confusion of self and the vision of truth? Between the chaos of our days and the glimpses of order and love upon which we stake our faith? Between the If and the Is?

LOVE SONG

First came cancer of the liver, then came the man

leaping from bed to floor and crawling around

on all fours, shouting: “Leave me alone, all of you,

just leave me be,” such was his pain without remission.

Then came death and, in that zero hour, the shirt missing

a button.

I’ll sew it on, I promise,

but wait, let me cry first.

“Ah,” said Martha and Mary, “if You had been here,

our brother would not have died.” “Wait,” said Jesus,

“let me cry first.”

So it’s okay to cry? I can cry too?

If they asked me now about life’s joy,

I would only have the memory of a tiny flower.

Or maybe more, I’m very sad today:

what I say, I unsay. But God’s Word

is the truth. That’s why this song has the name it has.

—Adélia Prado

“Let me cry first” is not in fact what Jesus said at the death of Lazarus. He didn’t say anything at all in the moment of that particular verse, which is famous for being the shortest verse in the Bible: “Jesus wept.” The least words for the largest sorrow. It’s hardly a paradox.

What is a paradox, though, is that Jesus weeps even though he knows what is going to happen: he will raise Lazarus from the dead. His knowledge spares him nothing. It’s almost as if “what is going to happen” is contingent upon human grief, as if fact had to pass through feeling in order to be fact. That the fact here is a miracle only intensifies the strangeness.

We know how, in psychological terms, time can get stuck in the mind and life of someone who has not learned to properly grieve. The scene with Jesus suggests that time itself becomes sclerotic without proper sorrow. What is “proper sorrow”? “I’ll sew it on, I promise, / but wait, let me cry first.” Or: “If they asked me now about life’s joy / I would have only the memory of a tiny flower.” The loose button on the shirt of a dying man, the memory of a tiny flower in the face of annihilating pain – the details scald with irony and irrelevance. And then they burn with love. The poem is not saying that the button and the flower and grief and God’s love are “related” to each other. It’s saying they are each other. In the terms of this essay, the if is the resurrection this poem implies (“God’s Word is the truth”). The is is the button. The if is what any honest faith looks like in this life. The is is the memory of a tiny flower. And they are all, for anyone fortunate enough to feel it, inseparable.

There is something both accidental and necessary, both salvaged and given, about these details and the vision of life that emerges from the poem. A whole new relation to reality seems possible. The Biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann says that what true prophetic witness enables is just such genuine newness. (This is what distinguishes such witness from the head-beating-on-the-wall method of Chekhov.) We don’t want newness, though, not really. “It puts us next to the ‘therefore’ of God,” as Brueggemann says, which might cost us our comforts and achievements, our treasured despairs. It might cost us, us. “Nothing but grief could permit newness. Only a poem could bring the grief to notice.” Both true. Both ambiguous gifts of God. And that’s why Prado’s poem – and this essay – have the names they have.

Excerpted from Christian Wiman, Zero at the Bone (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, December 2023). Copyright © 2023 by Christian Wiman. All rights reserved.

Footnotes

- Heschel actually says that “history is devoid of poise,” but he clearly means to include the current moment and thus all of time.