Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Editors’ Picks: Issue 26

-

Little Women, Rebel Angels

-

Sojourner Truth

-

Covering the Cover: What Are Families For?

-

Another View: Sunday Supper

-

Proteus Unbound

-

The First Society

-

The Corporate Parent

-

Family Matters

-

Letters from Readers

-

Family and Friends: Issue 26

-

The Case for One More Child

-

The Best of Times, the Worst of Times

-

Return to Vienna

-

You Can’t Go Home Again

-

Two Poems

-

Why Inheritance Matters

-

Not Just Nuclear

-

Dependence

-

The Praying Feminist

-

Letters from Death Row

-

The Beautiful Institution

-

Putting Marriage Second

-

Singles in the Pew

-

New Prince, New Pompe

Manly Virtues

Can Masculinity Be Good?

By Noah Van Niel

January 22, 2021

Available languages: Español

“Sing about that, bitch!” he spat, pushing my helmet into the turf. I made sure I’d cleared the first-down marker, tossed the ball to the referee, and jogged back toward the huddle, chuckling. Their linebacker had done his homework – news had recently broken that Harvard’s starting fullback was also an aspiring opera singer, and my resulting fifteen minutes of fame were easily discoverable by our opponents.

But as press coverage spread, it became clear that when people asked, “How can you do both those things?” they didn’t mean “How do you find the time?” or “How did you develop such diverse interests?” They wanted to know how I, a man, could do two seemingly antithetical things. Football players are tough and aggressive, manly; opera singers soft and effeminate. You can’t be both.

This is, of course, untrue. A number of football players have turned to careers in opera, many much more accomplished than I ever was. But the question wasn’t really about football or opera. It was about what it means to be a man. Over the years this sort of debate about masculinity has had many iterations, but recently it has become a full-blown crisis of identity.

In 2019, the American Psychological Association (APA) designated “traditional” masculinity as harmful. The APA described “a particular constellation of standards that have held sway over large segments of the population, including anti-femininity, achievement, eschewal of the appearance of weakness, and adventure, risk, and violence” that have led to increased rates of suicide, substance abuse, violent behavior, unwillingness to seek medical or psychological help, and premature death for men. “Traditional” masculinity – or “toxic masculinity,” in the now-common phrase – was killing us.

The author as starting fullback for Harvard Photographs courtesy of the author

In establishing these guidelines, the APA was coming out strongly on one side of a contentious debate. That men were in crisis was not news. In her 2010 Atlantic cover story “The End of Men,” Hanna Rosin explored ways men were falling behind women in education and career achievement. Others have since written articles and books exploring cultural and biological factors that might explain men’s dysfunction – for example, their brain development and learning styles, or their testosterone levels and natural aggressive tendencies. Perhaps it has to do with overbearing mothers and absent fathers, or with Hollywood movies and violent video games. Maybe it’s ease of access to online pornography, or the militant feminism that makes men feel like criminals before they do anything wrong.

This debate occurred in the midst of new conversations around gender identity and sexual orientation that added nuance to those topics but also left some men confused about how they fit into this new spectrum of gender fluidity. Meanwhile, through the #MeToo movement, women courageously exposed patterns of sexual harassment and abuse by men in many corners of society. The movement was long overdue, but swift in its coming, leaving many men unsure how to navigate a rapidly shifting cultural landscape.

John Wayne Masculinity

But was “traditional” masculinity as diagnosed by the APA really to blame? Or was it actually the overthrow of masculinity that robbed men of their self-confidence and left them confused about what it meant to be a man? In recent years, many have reverted to the “traditional” model as an ideal to be recovered, not a distortion to be rejected. It is perhaps emblematic of our divided times that John Wayne – the steel-jawed tough guy of mid-century war movies and westerns – has reentered the conversation as an ideological Rorschach test. For some he represents everything right and good about how to be male. For others he is everything that is wrong, toxic, and detrimental.

John Wayne in the film Hondo, 1953 Image from Alamy. Used with permission.

Defenders of John Wayne masculinity have been having something of a moment. The election of Donald Trump seemed to legitimize the resurgence of the tough-guy machismo so familiar from US history since its inception. In 2016, as #MeToo hit the headlines and women’s marches the streets, many men retreated online to nurse their wounds and try to sort out a way forward. Over the past four years, the internet has made major celebrities of a new generation of psychospiritual gurus trying to reiterate and recover traditional masculinity. No one exemplifies this trend more than Jordan Peterson, a Canadian polymath who promises men a treasure map to meaning.

What makes Peterson alluring to many men? From outside his fan club looking in, what’s striking is that he does more than just reject identity politics and political correctness: he promises to bring order to the chaos men find themselves in. Confusion seeks out clarity; crisis begs for commandments. So Peterson came up with clear steps for people to follow; his book 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos has sold over three million copies. You don’t need to endorse all of Peterson’s prescriptions, grounded as they are in his gender-essentialist views and in Jungian psychology, to recognize the power of what he offers to so many confused young men.

Christianity has joined – and sometimes led – the movement back toward John Wayne–style masculinity.

Peterson’s rise in popularity helped expose the reality that it’s far easier to deconstruct John Wayne–style manliness than it is to replace it. Those who classify “traditional” masculinity as “toxic” seem reluctant to put forth a constructive alternative, and not without reason. In their view, articulating any definition of non-toxic masculinity would be inherently reductive: to speak to men as men and not as individuals, they would say, is unavoidably to shore up a gender binary that should be dismantled.

Yet in the absence of positive alternative visions of masculinity, the vacuum has been filled by those who speak with force and clarity – for better or (more often) for worse. There is a growing audience not just for people like Peterson, but also for more troubling voices like that of Gavin McInnes, whose Proud Boys organization has traveled the slippery road from encouraging male empowerment to backing white male supremacy.

Men in Church

One hard-to-ignore development of recent decades is how Christianity has joined – and sometimes led – the movement toward an impoverished and brittle understanding of masculinity. One place this can be found is in the “men’s ministries” or the “men’s movement” in American Christianity, specifically in its Evangelical arm. More generally, Evangelicals’ theological understanding of patriarchal authority, complementary gender roles, and heterosexuality allows them to speak strongly on issues of gender in a way that gives them outsize influence. And indeed, for over a century, Evangelicals have been fighting to make their men spiritual warriors in the traditional, patriarchal mode of militant masculinity.

This is the argument the historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez makes in her new book Jesus and John Wayne. According to Du Mez, one should understand the masculinity promoted by Evangelical Christianity as motivated culturally just as much as it is theologically and biblically. Evangelicals concluded early on that the postmodern world, with its shift from the industrial to the intellectual economy, was stripping men of their God-given roles as providers and protectors. But in seeking to counteract this, Evangelical Christianity ended up promoting an ideal of the Christian man that had much more in common with the macho ideals of popular culture than it had with Jesus Christ. Influential Evangelical leaders such as James Dobson, Pat Robertson, and Jerry Falwell unabashedly glorified culturally defined masculine attributes, seeking to make Christian men rugged, aggressive GI Joes for Jesus. Through TV, radio, books, pamphlets, and conferences, this view of masculinity spread. To be sure, there were groups that offered a different vision – Promisekeepers, which had its heyday in the 1990s, perhaps most notably – but it appears they were effectively drowned out.

The Jesus of the Gospels proves an inconvenient stumbling block to those promoting ideals of patriarchal, aggressive, militant, dominant masculinity.

Whether or not one agrees with Du Mez’s wider argument, she is right to point out that the Jesus of the Gospels proves an inconvenient stumbling block to those promoting ideals of patriarchal, aggressive, militant, dominant masculinity. So those drawn to the idea of Christ-as-badass are forced to look elsewhere. They tend to emphasize not Jesus the man but the cosmic Christ, the eternal judge to whom all powers submit and obey: a figure more in the mold of John’s Revelation than his Gospel. And, of course, they are keen to pick up on the warrior heroes of the Old Testament.

Accordingly, these Christians rail against the “sissified Sunday School Jesus” of mainline Protestantism – what megachurch pastor Mark Driscoll called the “Richard Simmons, hippie, queer Christ.” For Driscoll, Jesus was “an Ultimate Fighter warrior king with a tattoo down his leg who rides into battle against Satan, sin, and death on a trusty horse.” According to Du Mez, it’s no coincidence that in 2016, 81 percent of white Evangelicals voted for Donald Trump, who claims to embody many aspects of this militant masculinity, nor that Trump was endorsed by John Wayne’s daughter.

To the extent that Du Mez is right, Christian masculinity has been defined more by culture than by scripture – and so it has little to offer men beyond the toxicities of the “traditional” model.

Behold the Man

But Christianity does have more to offer. It has at its core the person of Jesus Christ, God made man. Turning away from his personhood leaves Christian men without a compelling alternative; turning toward it offers growth through a masculinity emphasizing compassion, humility, and purpose.

Compassion: Compassion is Jesus’ driving force. Repeatedly the Gospels tell us that he is motivated by compassion: for the sick, the suffering, and the sinful. He never refuses someone who comes to him in need – Jew, Samaritan, or Roman; man, woman, or child. Emulating Christlike compassion requires care for others: friends, strangers, enemies. It requires showing mercy and granting forgiveness; to Jesus no one is beyond redemption. Compassion leads men to be healers and helpers rather than dominators or destroyers.

It also requires cultivating an emotional openness that allows one to feel the sorrow and pain of others. Emotional detachment, stoicism, the repression of feelings – some of those “traditional” male qualities the APA warned against – are the antithesis of compassion. Jesus wept at the death of his friend Lazarus. He admitted when he was afraid: “I am deeply grieved, even unto death,” he tells his friends (Matt. 26:38). By learning from Jesus’ emotional intelligence and using it to connect deeply with others, a Jesus-based masculinity encourages availability in personal and professional relationships and openness to the richness at the heart of Christian life.

The last three decades have brought a spate of books on Christian manhood.

Humility: Humility was another cornerstone of Jesus’ life. “All who exalt themselves will be humbled and those who humble themselves will be exalted” (Luke 14:11). The value he accorded humility increased his anger at the scribes and Pharisees he thought were greedy and self-indulgent, seeking places of honor at the table and making public shows of their piety. Instead, he says, “the greatest among you will be your servant” (Matt. 23:11). That is what he models for his disciples by washing their feet the night before his death, and it is how he understands his mission: “The Son of Man came not to be served, but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many” (Matt. 20:28).

Jesus doesn’t use his power to show off or control others; he rejects Satan’s offer of the splendors of the world. His power is for the powerless, made great by being given away. To the poor, the oppressed, and the persecuted he proclaims, “Yours is the kingdom of heaven.” So much trouble in the modern world comes from the misuse of power, out of confusion and ignorance as well as greed and lust. Jesus offers a clear way out: if we do as he does, we will renounce the drive for supremacy and dominance, stop glorifying our own strength and authority, and pursue humility and service, lifting up others, not ourselves.

Purpose: One shouldn’t make the mistake of thinking humility means passivity and weakness. Jesus worked hard, traveling the countryside so people could hear and follow him: “My mother and my brothers are those who hear the word of God and do it” (Luke 8:21). He wants people to bear good fruit; to multiply the gifts they have been given, not bury them in the ground. He wasn’t afraid to offer a harsh word or to point out hypocrisy and injustice. But he was also patient. He invited people to follow him; he didn’t force them. He was willing to listen to those he disagreed with and to engage in debate with them. He refused to fight them physically because he knew that “all who take the sword will perish by the sword” (Matt. 26:52). To call such a man weak is to mistake peacefulness for passivity, sacrifice for surrender. There is nothing weak about the cross.

The world does not reward men for being like Jesus – it certainly didn’t reward Jesus for being like Jesus.

Some men have responded to today’s confusion with loss of purpose or malaise – they’ve been called the “omega” males, the “failsons.” They give up on school, give up on jobs, fall into slothful routines, and don’t seem to care much about anything or anyone. Jesus offers men a purpose that calls them out of themselves to serve others – without letting that purpose become another instrument for control.

A Higher Challenge

Compassion, humility, and purpose are only a few of the qualities Jesus asks us to embrace. His honesty and integrity would discourage the lying, cheating, and stealing that infect many men’s hearts and poison their relationships. His pacifism would be a powerful response to the glorification of violence and aggression. His faithfulness to God might help men who are drifting from organized religion. His lack of attachment to worldly goods could help them resist connecting their self-worth to paychecks or possessions. And his commitment to combating injustice could inspire more men to use their privilege to fight for those with less.

Looking closely at the man Jesus shows us how far we have strayed. But it also makes clear his offer of a new way – in fact a very old way – of conceiving what a man should be.

Following Jesus will always be harder than following a Jordan Peterson. He calls men not only to swim against the cultural tide but to overcome what they have been told are irresistible drives for domination and sex. The world does not reward men for being like Jesus – it certainly didn’t reward Jesus for being like Jesus. You won’t get paid much, you won’t get famous, you won’t get the riches of this life by walking the way of Christ.

But you will become free. Jesus, God made man, shows us a way to transcend our baser selves and find a fuller, happier, healthier life. For Christian men who are desperate for guidance to chart a way in the modern world, the key is rooting their masculinity where the lives of all Christians should be based: in the timeless truth of Jesus Christ.

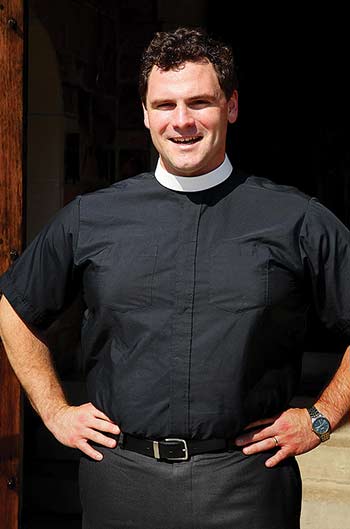

The author as Episcopal priest

My football and singing days are long over. The path of my life has led to new, even more fulfilling roles as husband, father, and priest. They may not be as newsworthy, but they repeatedly call me to consider the kind of man I want to be, and the kind of men I want to encourage others to be. I have two sons. It will be a challenge to teach them how to be men in this world, particularly men of faith. I want to tell them how to be while still giving them enough space to figure out who they are. How do I allow them to love knocking over piled-up blocks but make clear that real violence and destruction are things they should avoid? How do I keep alive the fun of wrestling and competing and yet make sure domination and winning don’t become too large a focus? How do I respect their emotions but encourage them to stop crying when someone takes a toy?

And this is all happening before they are affected by the wider culture, long before their testosterone kicks in. I want them to love being boys and men; I want them to be loving boys and men. I want them to thrive in this world and contribute to it. But most of that lies beyond my control. So instead of fretting about what kind of men they turn out to be, perhaps the best thing I can do for them is to introduce them to Jesus Christ and let them hear for themselves his ageless call, “Follow me.”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Betty Estes

Beautifully written and easily understood. The last sentence is perfect.

Don Neufeld

This article offers some important insights into the critical topic for men, and thus for all who love and live with boys and men. We as a Christian church need to look at our own contributions to some of the worst of men's behaviour, and the teachings that fortify the toxic images that plague men's experiences of themselves. Most importantly, we need to envision and promote healthy images for boys and men to aspire to. Definitely we have work to do on questions of gender essentialism (are men and women fixed entities that are mutually exclusive in character and role?), of men's mental health, addictions and violence, and the deep crises that lead so many to end their own lives. We need to challenge the assumptions of the dominant conversation on gender that leaves men marginalized, only making the appearance as potential perpetrators. As a social worker with over 30 years experience, with a passion for the church and theology, I offer this resource to the conversation: Peaceful at Heart: Anabaptist Reflections on Healthy Masculinity.

MICHAEL NACRELLI

I highly recommend the book "Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood" for a thorough treatment of this subject.

Michael Pennanen

The essay Manly Virtues: Can Masculinity Be Good? by Noah Van Neil provides an illuminating overview of current cultural debates and misguided Christian perspectives on masculinity. In that respect, Van Neil’s analysis is on target. However, he leaves us with an unsettled question: What outlook and behaviors, if any, are specifically “masculine”? Van Neil proposes that to express Christian manliness, a man must stay true to Jesus’ compassion, humility and purpose. This is a welcome corrective to faulty cultural assumptions about manliness. Still, does Van Neil mean to imply that women cannot manifest these same virtues? Given the tone of his essay, I don’t imagine so. Is it possible to be Christlike in ways that are distinctively masculine? The notion has its appeal. Certain traditional expectations (e.g., a man will be decisive) are satisfying to many people of either gender. Can we affirm such qualities in men without treating them as if they’re more naturally a male characteristic? Undoubtedly, more sorting-out of these matters lies ahead. Ultimately, though, I believe we’ll have to acknowledge that there’s no ideal combination of “Christian” and “masculine.” In God’s design, there’s too much variety among us to allow for such neat categories. For each of us, gender—along with our other traits and gifts—will have its role in shaping our unique Christian witness. As these various influences join together, may we each discover how to be Christlike in ways that express our own makeup and complement the gifts of others.

Fr William Bauer PhD

God created men and women. You wanna argue about His abilties?

Jessamine Hyatt

I think that Van Niel sets up the problem well, but at the end, I'm left with a big question: What distinguishes his view of positive masculinity from a positive femininity? If Jesus is the role model for men, who is the role model for women? Are not all Christians meant to emulate Jesus, whatever their gender? Compassion, humility, and purpose: I have no argument with encouraging men to aspire to these virtues, but I see nothing essentially masculine in them. As commenter Grace May puts it, it seems to me that he is writing about "how to be truly human." I remain interested in the question of what does, or should, define a positive masculinity, and remain uncertain as to whether it is distinguishable from a positive femininity in the final analysis. Thank you for this thoughtful piece, and please continue the conversation.

Grace May

Noah Van Niel’s piece on how to be truly human is life-giving. By sharing from his own life and offering an alternative to toxic “manliness,” the author points us to the heart and actions of Jesus’ compassion, courage, and cross. What a grand vision of following Jesus that infuses our everyday lives and decisions with holy value so that our pursuits and aspirations bear the mark of a true disciple.

Larry A. Smith

Well done and thank you. I am sending it to my son who already exemplifies much of what you have written.

Bonnie P Biocchi

This is a refreshing article which underscores the need for the church universal to support positive role models of masculinity. Well-written, thought-provoking article which gives concrete advice for today's husbands and fathers.

Fr. Daniel Robayo

Outstanding analysis of the crucible in which we men navigate life and an insightful as well as inspiring call to follow Jesus. Thank you.

Edward Lee

A beautifully and thoughtful piece. Thank you for your words Noah.

Joe at Plough

Van Niel sets out his challenge to us dads: How do we raise our sons to model the manliness that Jesus exemplified? Anyone have real-life examples?