Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Sojourner Truth

-

Covering the Cover: What Are Families For?

-

Another View: Sunday Supper

-

Proteus Unbound

-

The First Society

-

The Corporate Parent

-

Family Matters

-

Letters from Readers

-

Family and Friends: Issue 26

-

The Case for One More Child

-

The Best of Times, the Worst of Times

-

Return to Vienna

-

You Can’t Go Home Again

-

Two Poems

-

Why Inheritance Matters

-

Not Just Nuclear

-

Dependence

-

The Praying Feminist

-

Letters from Death Row

-

The Beautiful Institution

-

Putting Marriage Second

-

Singles in the Pew

-

New Prince, New Pompe

-

Manly Virtues

-

God in a Cave

-

Editors’ Picks: Issue 26

Little Women, Rebel Angels

Louisa May Alcott and Simone de Beauvoir

By Mary Townsend

November 30, 2020

Simone de Beauvoir was not born an atheist; rather, she became one. In an inversion of Pascal’s Wager, the idea of any bargain with God seemed to her to be petty and beside the point. In her 1958 autobiography, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, she writes: “I could not admit any kind of compromise argument with heaven. However little you withheld from him, it would be too much if God existed; and however little you gave him, it would be too much again if he did not exist.” The logic of all or nothing was the only logic that satisfied.

Simone de Beauvoir Photograph public domain

Born in 1908, Beauvoir grew up in the thick emotive haze of leftover nineteenth-century French Catholicism, carried into pre-war France. She was educated in the same sort of immersive religiosity that provided plenty of opportunities for spiritual heroism from very young girls in particular, the same sort of upbringing that produced Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, the Little Flower, who aspired to sainthood from her very early youth and in her death in 1897. Beauvoir, who for several years aspired to be a nun, writes of the exquisite transports of confessional tears, imagining herself swooning in the arms of angels; she prided herself on inventing mortifications in her very few moments alone. But unlike Thérèse, Beauvoir found no lasting comfort within or even distantly alongside Christianity.

It was not by cutting herself off from transports of emotion or by abandoning the metaphysical all-or-nothing that she eventually found an image of adulthood she could live with; nor could the attractions of philosophy, which she first came across through the Thomism of her girls’ school, or the Catholic social justice group she volunteered for, do the trick. It was rather literature, as a kind of Art, and herself as Author, that managed to hold the strongest and most sustainable appeal as vocation. If you can believe it, the first non-saintly individual Beauvoir found really attractive was the fictional American Protestant, Jo March, one of the heroines of Louisa May Alcott’s wildly popular 1868 novel, Little Women. Beauvoir couldn’t quite escape the nineteenth century after all.

Like so many readers, the young Simone was passionately invested in the persona of Jo as a writer, taking up the genre of the short story to imitate her. Inevitably, she also had extremely strong opinions on the Laurie question, the wealthy neighbor who proposes to one and then another of the March sisters. Opening the second volume Good Wives by accident, she came upon Laurie and Amy’s engagement (without the help of Jo’s refusal for context), and her response was immediate and absolute: “I hated Louisa M. Alcott for it.” But the similarities between the Marches’ style of family life (fictionalized from Alcott’s own experience) and her own gave her pleasure: “they were taught, as I was, that a cultivated mind and moral righteousness was better than money.” This was something to hold on to, the more so because like the Marches, and like Alcott herself, Beauvoir’s family dealt with straitened means, the memory of better times, and the all-too-visible wealth and comfort of neighbors and relations. The reward of their virtue was to be found in the causes they took up: for Alcott, abolitionism and suffrage, and for Beauvoir, existentialism, Marxism, and her own variety of existentialist Marxist feminism. The necessity for strict social circumspection in the behavior of daughters was lost on Simone, Louisa, and Jo alike.

Louisa May Alcott

This funny crisscross between Alcott and Beauvoir’s lives continues to tease at my sense of the significant, with the added coincidence of the Greta Gerwig film and a new biography of Beauvoir from Kate Kirkpatrick, both coming out in the last year. The film is lovely, although I’m somewhat distant from it as a fan; I, too, read Little Women with pleasure in my youth, but it never seemed the reflection or the idealization of my childhood. In fact, it was only when I read Beauvoir’s Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter that I had a reading experience analogous to what many report about Alcott, where the author’s descriptions seem to correspond to or call forth some memory of my own. I grew up in the former French colony of Louisiana, in the post-Vatican II Roman church; like Beauvoir, I had one younger sister, one devout parent and one more skeptical, a large extended family to visit, a white dress at first communion, and the confessional ready to absolve even the smallest of the week’s sins. Alcott’s landscape, by contrast, was foreign to me. That the Marches pay such close attention to regretting faults in their behavior, that they give up wine (give up wine for life, not even at a wedding),that they worry over whether they’ve allowed their passions too much sway – all of these are fundamentally un-French attitudes taken by no adult I knew well. To me, the Protestant world of Little Women read as fantasy.

Simone also finds the Marches’ Protestantism somewhat puzzling, the one wrinkle in their otherwise close correspondence. She read Little Women in English; the French translation converts Mr. March into a doctor, the better not to scandalize its readers with married clergy. The Marches had their Pilgrim’s Progress, but Beauvoir’s mother gave her Thomas à Kempis’s The Imitation of Christ. Beauvoir makes her first communion in tulle and a veil of Irish lace (not the ensemble in vogue in 1980s Louisiana, alas for the age). But Meg’s and Amy’s continual mortification at the plainness of their teen clothes, so like Simone’s at their age, was a truth of life and of religion that Beauvoir could not forgive. One day a new girl arrives at her school who is rather better dressed than others: “her bobbed hair, her well-cut jumper and box-pleated skirt, her sporty manner, and her uninhibited voice were obvious signs that she had not been brought up under the influence of Saint Thomas Aquinas.” Despite Simone’s preference for Jo, it’s obvious she is a bit of an Amy; she retains a relatable desire to be beautiful and admired that is charming, a reason why you love her, a forgivable but real flaw in her character. In Beauvoir’s novels, each stand-in for herself wanders around Paris and the globe, still wanting new ways to be adored.

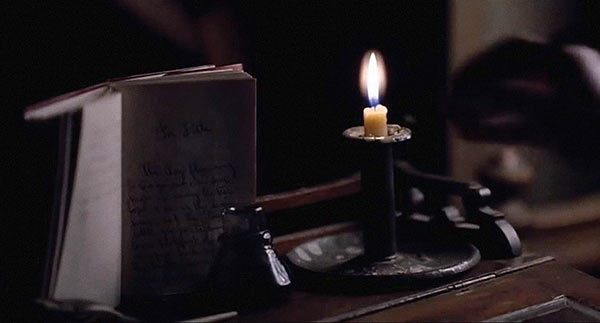

Still from the 2019 film adaptation of Little Women by Greta Gerwig. Photograph from imdb.com.

The object of Simone’s own youthful adoration was her best friend, Zaza, written into her memoirs as narrative foil to her own dreams of rebellion. Together they navigated teen life at their school nicknamed Le Cours Désir, where Catholicism was the justification provided for various odd expectations. Zaza’s mother, who had eight other children as well, “would have thought it immoral to buy in a shop products that could be made at home: cakes, jams, underwear, dresses, and coats.” This was not so much for the sake of thrift – thrift being a virtuous but unnecessary ideal for the young women expected to marry men who owned the means of production – as it was a source of desperately needed occupation: the life of wearing beautiful clothes and sitting up straight at correct social gatherings can only take up so many hours of the day. And so Zaza is sent out to compare the prices of cloth or set to work canning great quantities of jam so that she’ll have hardly any time to talk to Simone. (In The Second Sex Beauvoir is particularly virulent about the destructive tendencies of making jam.) “Zaza,” Beauvoir writes with a certain jealousy, “was too much of a Christian to dream of disobeying her mother.” But while Zaza obeyed, she also felt the oddity of what religion was asking, on behalf of religion, all the same: “she couldn’t bring herself to believe that by trotting off to shops and tea-parties she was observing faithfully the precepts of the Gospel.”

The minor privations of Beauvoir’s Paris youth pale beside Alcott’s, whose family was not only poor but often poor via the pursuit of otherworldly ideals; during their days as fruitarians, the gossip was that Alcott’s father forbade them to grow potatoes, on account of their earthly nature. But there are elements to Alcott’s life that could well have struck Beauvoir with envy. Beauvoir’s higher education came about because her family could not afford to marry her off with the customary dowry, and so she was sent to school to become a teacher. Her father considered her learning a shameful manifestation of his failure, and told her she read too much. For Alcott, on the other hand, while it was no joke to have as one’s father a failed Utopianist, wage-refuser, and sometime philosophe who somehow never was able to get his best thoughts onto paper, still her family situation came with certain benefits. Bronson Alcott did take Louisa’s education seriously, and her family’s connections to the transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson, the abolitionist William Garrison, and the Unitarian minister Theodore Parker meant that radical philosophy, radical politics, and radical religion were a natural part of family life – not something desperately held at bay by frantic parents.

To me, the Protestant world of Little Women read as fantasy.

Beauvoir, with her budding social conscience, was vaguely assured by authority figures that the condition of the workers was much better these days. Later, she would insist on seeing for herself, traveling far to witness different social conditions at work; her visits to America involved her in a study of the effects of segregation, which proved to be a major impetus for writing The Second Sex. Philosophy, including the political sort, became the medium of revolt by which reality, in all its suffering, could finally be truthfully seen.

For Alcott, by contrast, radical care for the poor – not just helping them out on occasion, but trying to think about what social conditions would end poverty – was the Christianity she knew from early youth. The freedom to experience faith in this way is part of the charm of the March girls’ lives, even though you can hardly tell from any single word they drop that abolition is on their minds; Beauvoir’s freedom to let her politics form an overt part of her published works might well be envied by Alcott in turn. It’s fascinating to see how their very similar youthful religious experiences were taken in completely different ways by the people who surrounded them. Alcott writes: “A very strange and solemn feeling came over me as I stood there, with no sound but the rustle of the pines, no one near me, and the sun so glorious, as for me alone. It seemed as if I felt God as I never did before, and I prayed in my heart that I might keep that happy sense of nearness all my life.” For a Unitarian, this was a perfectly reasonable expression of Christianity. But for Beauvoir, it was trying to communicate something like this and failing to have it taken seriously that finally put an end to her interest in religion.

The main problem with the way religion was taught to her, Beauvoir writes, however, was that it formed the truth of one sphere of observable life but not of another: “Sanctity and intelligence belonged to two quite different spheres; and human things – culture, politics, business, manners, and customs – had nothing to do with religion.” At first this split was merely puzzling; then Simone smelled a rat. When Pope Leo XIII called for a living wage for workers in Rerum Novarum (a moderate position that disavowed anything so threatening as socialism or the abolition of private property), her parents still complained that he “had betrayed his saintly mission,” which forced their daughter “to swallow the paradox that the man chosen by God to be His representative on earth had not to concern himself with earthly things.”

At university, however, Beauvoir engaged with these ideas via the work of her professor Robert Garric, a “social Catholic” who spoke of providing cultural and intellectual opportunities to the working classes. In him she could admire the co-incidence of idea and life that was missing elsewhere: “At last I had met a man who instead of submitting to fate had chosen for himself a way of life; his existence, which had an aim and a meaning, was the incarnation of an idea, and was governed by its overriding necessity.” But she never left behind the taste for the all-or-nothing, her “nostalgia for the Absolute”; as she later famously declared, even socialism was not enough, in her opinion, to bring about women’s liberation; the Revolution was needed.

Beauvoir was critical of this aspect of herself, even willing to joke: “a socialist couldn’t possibly be a tormented soul; he was pursuing ends that were both secular and limited: such moderation irritated me from the outset. The Communists’ extremism attracted me much more; but I suspected them of being just as dogmatic and stereotyped as the Jesuits.” Beauvoir’s 1954 novel The Mandarins is a master-class on the fragmentation and foibles of the passionately self-critical left, as its members scrabble to unite themselves after the atrocities of World War II. And her life, devoted to activism not less than to writing, exemplified the co-incidence between word and deed she sought. Crossing the globe to meet with feminist and Marxist activists, writing endless letters in response to readers of The Second Sex, she also made her mark at home: Beauvoir’s journalism helped tip the balance of French public opinion towards ending the colonial occupation of Algiers.

The main problem with the way religion was taught to Beauvoir was that it formed the truth of one sphere of life but not of the rest.

The roman church of Louisiana in the 1980s was and was not the church of Simone’s youth. No one asked for mortifications, Rome was far away, and so was France; the last nun at Immaculate Conception Cathedral School, Sister Hélène, died the year before I would have had her as my teacher. Perhaps enabled by this distance, in 1984 Louisiana was the site of the first successful public prosecution of a priest who sexually abused hundreds of children, in the diocese only a few miles away from mine – a fact that not a single adult mentioned to me, not once, although they did tell me continually to watch out for pedophiles. There was a statue of Saint Vincent de Paul, patron saint of service to the poor, in a little garden outside our church; it was never clear to me just what he was supposed to be famous for.

Still from the 2019 film adaptation of Little Women by Greta Gerwig. Photograph from imdb.com.

For our family, Catholicism was a matter of genetics; it certainly wasn’t about morality. Certain rules, slightly more complex than those of the other, déclassé denominations, gave a shape to what was allowed and what was not. Everyone lived within and without these rules simply as it happened; if someone needed an annulment, it would be granted eventually, it would just take a while. In Catholic school we learned arguments to defend this complexity from charges of arbitrariness; this somehow formed the totality of theology. It was lacking something, though we knew not what. As Beauvoir puts it, “I had subtle arguments to refute any objection that might be brought against revealed truths; but I didn’t know one that proved them.”

For me, the problem wasn’t so much the proof; epistemology is my least favorite branch of philosophy; it’s much more interesting to learn all about things than waste time on how it’s possible I know them in the first place. What was missing was more essential. In college I read Martin Luther’s On the Freedom of a Christian (1520) for the first time. When revelers from the annual campus party interrupted our seminar after a few minutes, I threw my copy against the wall with abandon. I’d never read a text like it; to me at first it seemed like pure absence of thought. But I returned the next morning to the classroom to fish it out of the corner; it wasn’t apologetics, but something simpler. The truth, whatever it is, will set you free. I could live with that.

Beauvoir’s satisfaction in simple negation of everything religious makes visceral sense to me; I know exactly how it felt because I had to experience it too. To sweep everything away, the artificial constructions, the apparent contempt for the female body and its redemption by self-inflicted wounds, the insistence that human (male) authority was holy of itself, that it could always ultimately be trusted: the truth was a prefabricated goal without drama to its completion.

Still from the 2019 film adaptation of Little Women by Greta Gerwig. Photograph from imdb.com.

More than this, it wasn’t satisfying to be told that there is one season for examining your conscience, as helpful as it is to have a season, with the rest of the year as good as carnival; the power of the confessional takes on a levity in the hands of the youth, a game to play as you get in and out of sin, that’s uncomfortable to behold. When I first read Plato I was immediately entranced: here is someone who shows that philosophy is not something to pick up and put down but the only way to really live; someone who hated the love of ignorance as much as I did. Plato, however, notoriously points back up out of the world to a good that permeates it but can’t be of it – quite.

After one negates the given, any good Hegelian can tell you, there must come a synthesis which contains both the given and its negation in subtler form. Beauvoir, who was otherwise a good Hegelian and knew this well enough, never got there with her negated faith because she didn’t want to. She tried to satisfy herself with earthly loves; we love her novels because in them she admits it never worked. In her youth, Beauvoir would go into churches to sit with a quiet moment; I still do the same. But what a relief it is not to be sorry that I can let myself in good faith want the thing the building is supposed to house – the thing that the atheist says, with impossible absolutism, cannot exist, and the thing Aquinas says, too blithely, that all men speak of as God. To be the heir not of the nineteenth century but of Beauvoir’s rebellion is unmerited gift; I’ll take it.

Finally, one night, failing to summon God directly then and there, Beauvoir called it quits.

Beauvoir was happy in college, though she didn’t quite find any author from the history of philosophy she felt she could trust; the interpretation of Plato that she was offered seems particularly uninspired, and no one taught Hegel or Marx at all. She thought literature was a better medium than the “abstract voice” of philosophy, but she struggled with the idea of writing as vanity. In this phase, she grew thoughtful about the possibility of mysticism – she picked up Plotinus and tried to think herself into some direct revelation of the absolute. “In moments of perfect detachment when the universe seems to be reduced to a set of illusions and in which my own ego was abolished, something took their place: something indestructible, eternal; it seemed to me that my indifference was a negative manifestation of a presence which it was perhaps not impossible to get in touch with.” She asked her Catholic peers and a teacher if she was on to something. They said no. Her confessor had long ago made it clear he had nothing to say to her doubts.

Finally, one night, failing to summon God directly then and there, she called it quits, concluding, “I should have hated it if what was going on here below had had to end up in eternity.” And so her atheism remained on the books. But this remark is at odds with her sense of the importance of art and its promise of longevity, and so at odds with the work of her life.

Her truer feelings are perhaps expressed by this: “If I were describing in words an episode of my life, I felt that it was being rescued from oblivion, that it would interest others, and so be saved from extinction.” This sentiment is uncannily echoed in the dialogue of Jo and Amy (as Gerwig renders it in the movie), when they discuss why the writing of a family life of women might have any importance. In the end, Beauvoir as artist and philosopher holds on to this kind of eternity, at least, and with a brilliance that makes me not only full of love but of pride – proud of her and each of the beautiful things she managed to write despite their imperfections, as proud as I am of Alcott for her work and her life, and as proud as we all are of Jo. Not nostalgia but pride, I realized, was my primary feeling when watching Gerwig’s film: not in Alcott’s perfection, or Gerwig-Jo’s aesthetically embalmed autonomy, but that Alcott wrote, and that we read. Beauvoir was not wrong about art.

Still from the 2019 film adaptation of Little Women by Greta Gerwig. Photograph from imdb.com.

She did not learn Jo’s lesson, though, or perhaps she learned it too well: she chose a Laurie for a partner after all, or rather a Professor Bhaer (the man Jo did marry) who in her story retains several aspects suspiciously reminiscent of Laurie’s worst qualities. That is to say, Beauvoir found Jean-Paul Sartre, and retained the need to praise him, even when he didn’t deserve it. And though, as Kirkpatrick’s biography helpfully reminds us, Beauvoir was an existentialist and a philosopher long before Sartre failed his first attempt at the Sorbonne’s exam – and then needed her help understanding Leibniz, Husserl, Hegel, and so on – we still see her commitment to what she insists is his philosophy, even when describing what was her idea in the first place. When Beauvoir’s writing stumbles it’s often because it suddenly has a tinge of the apologetics she otherwise despises, that is, when she feels it necessary to apologize for Sartre. That her writing so often successfully breaks free of this, as she in her private life soon broke free of Sartre as partner or idol in truth (after a few months together she declared him a friend of her heart, rather than a subject of lasting adoration), is a testament to the reality of her commitment to freedom as the highest good.

Sartre, in his philosophy, could never quite let go of the willful misreading of Hegel that his youthful self persisted in. It comes down to the dialectical relation between Hegel’s master and slave: Sartre took this passage to mean that the human being could never outrun its desire to dominate the Other, of whatever variety: the foreigner, the worker, your lover, the person you pass in the street. Beauvoir wrote The Ethics of Ambiguity (1947) in order to defend existentialism against the charge that it lacked a coherent ethics; but her ethical philosophy reached coherence through the understanding that only by willing the freedom of the Other can one reach an authentic understanding and practice of the freedom each individual longs for. This is closer to what Hegel really said. Why was Beauvoir able to listen? She writes: “My Catholic upbringing had taught me never to look on the individual, however lowly, as of no account: everyone had the right to bring to fulfillment what I called their eternal essence.” Beauvoir kept what faith she could.

I think Beauvoir settled on atheism because she was unable to imagine an intellectual Christianity. This was not because intellectualism was lacking from the Thomism or Catholic existentialism that she had come across, but because what she wanted was the freedom of a Christian, the freedom to understand God, truth, the Absolute on her own terms, and she was told that there was no way to do this. There’s an irony in her captivation with Sartre’s vision, which she found novel, of the freedom to will one’s own future – all too strangely reminiscent of the argument Luther made in 1520. For Beauvoir, the blind nationalism of the French Catholic church, its triumphal support of colonization, its unwillingness to call private property into question, failed to answer her desire for understanding a world in thrall to capitalism. One must think of Beauvoir as a rebel angel.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.