Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Two Poems

-

Why Inheritance Matters

-

Not Just Nuclear

-

Dependence

-

The Praying Feminist

-

Letters from Death Row

-

The Beautiful Institution

-

Putting Marriage Second

-

Singles in the Pew

-

New Prince, New Pompe

-

Manly Virtues

-

God in a Cave

-

Editors’ Picks: Issue 26

-

Little Women, Rebel Angels

-

Sojourner Truth

-

Covering the Cover: What Are Families For?

-

Another View: Sunday Supper

-

Proteus Unbound

-

The First Society

-

The Corporate Parent

-

Family Matters

-

Letters from Readers

-

Family and Friends: Issue 26

-

The Case for One More Child

-

The Best of Times, the Worst of Times

-

Return to Vienna

You Can’t Go Home Again

For an immigrant family, storytelling saves those you love from oblivion.

By Zito Madu

November 24, 2020

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

My father loves to tell the story of the time my older brother and I got lost coming home from a festival in a neighboring village. We grew up in a remote Nigerian village in Imo State, and though the gathering was within walking distance, it’s very dark at night out in the countryside.

My brother and I stayed at the festival much longer than we should have. By the time we began walking home, it had become difficult to see, and it was pouring rain. Maybe out of fear, or frustration, or simply because I was a difficult child, I eventually quit walking and sat down in the rain to cry.

My father, sensing that something was wrong, got on his motorcycle and set out to search for us. He rode around both villages, asking people if they had seen us. Eventually he found us on the side of the road. We rode back in the rain, my brother in the back and me clinging to my father’s neck.

The author and his older brother in Nigeria

When my father tells the story, he does it in such detail that it seems as if he has just lived that day. He remembers the festival we went to, how long we were gone, what time it was when he started being worried, the people he spoke to, the road he found us on. It’s as if he took detailed notes, yet there’s no notebook or recording of the event. He can simply recall it whenever he wants.

It’s not just his personal history and experiences that he recalls in such detail: our culture is passed along orally, and my father is a great storyteller. He has an almost encyclopedic knowledge of our village and our people. He knows the branches of families, their beginnings and entanglements. He knows the true histories of many of the villagers and the myths that have determined the village’s collective identity. Much of the information was passed down to him, but the rest he acquired on his own, listening and watching.

I envy my father’s memory, as I can barely remember anything. I have a theory that the difference between us is that he is a person of community, and I am not.

I envy his memory, as I can barely remember anything. I have a theory that the difference between us is that he is a person of community, and I am not. He thrives when surrounded by people and is uncomfortable in isolation. I choose to spend most of my time alone; it suits my nature. Solitude seems as if it should be suited to better memory, but it’s had the exact opposite effect. With no one to remember with, my memories tend to wither, leaving only broad outlines, and my brain constructs false memories to fill in the gaps.

I often ask my father to document the things that he remembers about our village and our family. He tends to agree, but never follows through. He has no need to write his memories down, because he has no fear of forgetting them. The request is secretly for me, both because I want to learn more about who we are, and because I know that I’m already forgetting so much.

Recently I bought some film to take pictures of the first house my family lived in when we moved to the United States in 1998; all eight of us lived in a single room on the second floor.

Encountering our landlord, Mr. Collins, was a saving grace. We had moved to Detroit for the Nigerian community, but as my mother tends to put it, “we were utterly abandoned” after we arrived. Mr. Collins allowed us to live in that room rent-free for the first few months, and when he found out that we all used to huddle around the sole space heater at night, he brought us cold-weather clothes that had belonged to his family.

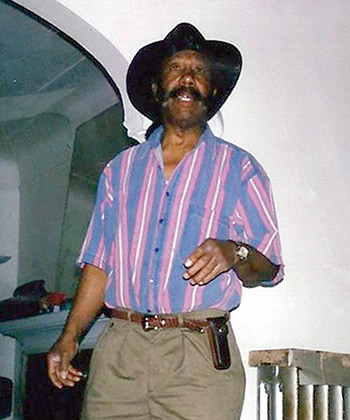

Mr. Collins in his younger days on a visit to the author’s family

Mr. Collins had a wife named Cookie and a son and daughter. The son lived on the first floor of the same house we were in for some time, but he struggled with drug addiction. Once, he fought my father after my father refused to give him money under Mr. Collins’s orders. Eventually the son moved out, first to another house nearby, and then he disappeared from the street and regular conversation. The daughter was better off. We saw her infrequently, but she was usually doing well.

Mr. Collins and his family provided us with small joys and relief in those harsh early years. They couldn’t erase the pressures of poverty and acclimating to a new world, but he and his wife tried to alleviate them as much as they could. Sometimes it was allowing us to skip rent, other times it was taking the children for ice cream or to ride horses.

Mr. Collins and Cookie took me and my siblings to our first circus. They bought us toy lightsabers. When my father went from Rite Aid stock boy to a different schedule as a wineseller, Mr. Collins began to pick us up from school. He would take us to Belle Isle, the island park in Detroit. I still have a picture from that time of me standing on the top of its iconic big slide. I know without seeing him in the photo that Mr. Collins was waiting at the bottom. He and Cookie helped us have a childhood when we could have been crushed by the struggles of the new world.

After we moved out and into our own house, we barely saw Mr. Collins anymore. Even though he was just a few miles away, the days seemed to press relentlessly against each other and there was so much chaos with everyone growing up and dealing with school and young adulthood. He came over periodically at first, but soon his own problems got too big as well. Somehow, though, my father seemed to stay in touch.

I was with my father when I last saw Mr. Collins and Cookie, who had dementia. The disease set on her and took over quickly. She didn’t recognize us, and she barely recognized her husband. Watching his wife wither, taking care of her as she grew even more distant from him, had a visceral effect on Mr. Collins. Stress stripped his body down to a skeleton, and he swam in the same clothes that had been tight on him before.

The author in front of his family’s first house in Detroit (collage)

Cookie died soon after our visit. About a year later, my father asked me if I wanted to go see Mr. Collins with him. I declined. I never got to see him again; soon Mr. Collins died as well.

I refused that final chance to visit because I wanted to avoid seeing him reduced by his troubles. I ran away from that encounter, but when I went to take pictures of the old house, connected so much to him and Cookie and the life they gave to it and us, I realized I was trying to capture what that first American home meant to me, to use photography as a tool of preservation. The house existed in a particular way in my imagination and I wanted to import it into memory, to translate it into something lasting. But all I saw was sadness and vanishing.

Time had done to the house what time does to everything. The essence of it had been washed away. I didn’t want to take pictures of it, or even to stand and look at it. After all the house had meant, it felt unjust to document its ruin. The same went for the man who owned the house.

Sometimes I feel as if I write as a form of excavation, an act of finding. But it’s inadequate for preserving the existence of the people and places I love – no number of words, however beautifully arranged, could ever revive their fullness. The irony is that the more I try, the more hollow and inadequate the result. In the face of this injustice, it almost seems that to be forgotten is better.

At the end of Julio Cortázar’s 1949 play The Kings, the dying Minotaur insists that he does not want to be remembered. “A lifetime of forgetting awaits you,” he tells his uncomprehending audience. “I don’t want tears; I don’t want statues. I only want oblivion. Only then will I be more myself.” I imagine this recrimination coming from the people and places I try and fail to recover.

About the time Mr. Collins died, my father told me that one of my cousins in Nigeria had died as well. “Cousin” might not be the technically correct term for how Chuks and his family are connected to me; village families are linked in so many ways that it’s difficult to untangle the details. Such an exercise is also unnecessary. He was my family.

Chuks was the youngest of six. His family had lived in a house in front of ours for generations and within that greater family, we also had generational friendships. Our own particular group of friends was my older brother and me, Chuks, and his two older brothers.

All we used to do in those days was play around. I barely remember school, but I remember playing soccer, playing by the school and church across the road from our homes, running through the fields at night to catch crickets, chasing bats from old buildings, and going to festivals together. My mother likes to remind me that whenever we all played, Chuks came home last – he lagged behind carrying the clothes and shoes that the rest of us had abandoned.

Cookie holding the author’s younger sibling

Years after we left, Chuks joined the church. He wanted to become a priest. He was walking home from Mass one night when he was killed; thieves hit him over the head with a blunt object. His body was found on the side of the road the next morning.

Chuks’s death gave me a double shock. The first was at the sudden finality of death. No matter how common that great catastrophe is, it still remains absurd to me. That someone can be present in the world and then not, especially through a ridiculous chance – that he was in the wrong place at the wrong time – seems so cruel and unacceptable. Now, with so many vanishing due to the pandemic, the grief is repeated and unfathomable; that so many people in the world can disappear so quickly and irretrievably is overwhelming.

The second shock came when I realized that I couldn’t remember his face. I had always taken joy in the fact that even though I hadn’t seen him in a while, he existed somewhere, struggling and striving, being and becoming, that he and his goodness were present in the world. When he died, not only did I feel the grief of losing that joy, it became apparent that my memory of him was vanishing. I couldn’t fully construct him anymore.

Almost ten years after leaving my old village, I went back to visit for the first time. When I arrived, it became evident that it wasn’t just Chuks I was forgetting. There was a natural sense of familiarity, but so much of the place where I grew up felt alien, as if things were slightly askew. I saw people I should have known but couldn’t remember, and I walked down roads I was sure I had been on before but couldn’t place. It felt as if my full memories of the place and its people were just slightly out of view, that all I needed to do was to focus hard enough and turn toward them. But as much as I tried, the full picture never returned. Naturally, my father had none of those problems and fit back in as if he had never left.

Mr. Collins with the author’s younger sibling

I spent most of my time sitting and talking with Chuks’s older sister, Chigozie, the last of his siblings who was still there. I told her stories of America, and she filled me in on what had happened since we left. Every morning I walked over to their house and sat with her until the evening, listening to her tell stories as I attempted to restore my memory of the place. The next time I went home, she had also left. I spent most of that visit confined to our house.

The word nostalgia combines the Greek roots for “return home” and “pain” – a painful homecoming. “What we think of as the present is made up of the past,” the poet W. S. Merwin once said about memory, noting this etymology. “Homecoming is what we all believe in. I mean, if we didn’t believe in homecoming, we wouldn’t be able to bear the day.” Forgetting means that I can’t go home, and that even at home in the village, I still feel far away.

That I can’t hold on to the people and places I cherish feels as if I am losing who I am. Worse, if I can’t remember them, I cannot testify to my love for them. In Adam Bede, George Eliot wrote: “Our dead are never dead to us until we have forgotten them: they can be injured by us, they can be wounded; they know all our penitence, all our aching sense that their place is empty, all the kisses we bestow on the smallest relic of their presence.”

That I can’t hold on to the people and places I cherish feels as if I am losing who I am.

My father has no need to write down his memories and probably never will. I think that as a community man, he understands that he is part of a larger story and a collective memory that is contained with him but also supersedes him. He has no fear that the story will disappear with him, because the story is the people as a whole.

In my own alienation from that collective memory, I find myself excavating graves to bring things back to the surface. The anecdotes I can muster don’t do them any more justice than the shards and bones of an archaeological dig do the fullness of the past. But in the process, I can at least bestow kisses on the smallest relic of their presence.

I never imagined becoming a writer, but now I write ghost stories out of desperation and hope against time and memory. It’s an impossible hope, but it’s one that I need in order to go home again.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Michelle O'Quinn

I love your beautiful and poignant story. It stirred memories of my own and reminded me to be present as often as I can, in every way, because my own discomfort always gives way to the joy of others and in my own heart. Especially when I do the uncomfortable things.

Dara

Thank you, I feel very similar to what you wrote.

Henry Decock

Thank you for a beautifully written article. The timeliness of my reading it is truly remarkable. I have also been digging into my families history through photographs after my parents generation has passed and there isn't anyone left to tell the stories. My hope is to recreate those memories as eloquently as your piece.

Joe C Ramunni

Thank you for sharing, your memories serve you well, as did your fathers. If you have not yet read "All Things New" by John Eldredge I would recommend it. Shalom Joe

Gabriel

So beautifully written that I found myself vividly imagining the father's descriptions of the festivals. Thank you so much for sharing