Cardinal Schönborn, archbishop of Vienna, talks with Plough’s Kim Comer about family history, celibacy, monument toppling, and the healing of memory.

Plough: The child Christoph Maria Michael Hugo Damian Peter Adalbert Graf von Schönborn was born at Skalka Castle in 1945 and entered the world laden with a certain status and certain expectations. Did this inheritance ever seem oppressive?

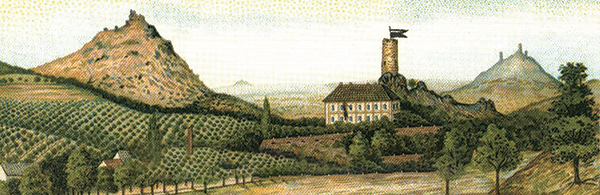

Cardinal Schönborn: I was just nine months old when we were forced to leave our family castle in Bohemia, along with the other two million ethnic Germans expelled from Czechoslovakia after World War II. The next time I was inside a castle owned by my family, I was eighteen. In the meantime, I lived very far from castles, as the child of a refugee family – mostly we stayed with relatives who put us up here and there.

It’s true that I was born into a family where certain things were expected of me, but I was the second son. My older brother would have inherited the family’s estates according to the rules of fideicommissum succession, under which the oldest son is the sole heir to avoid splintering the inheritance. My mother used to tell how, when I was born, the midwife held me up and said, “Poor little thing, you get nothing but the garden!” As it turned out, because of our family’s expulsion, I didn’t even get the garden.

Cardinal Schönborn Photograph courtesy of the author

Still, from early on, I was interested in my family history. I discovered that the great careers of members of the Schönborn family were always in the Church. I had no way of knowing that I would become the eighth bishop and the third cardinal in our family’s history.

These ancestors did not always act in accordance with our contemporary values. This past summer, around the world we saw monuments toppled because of the sins of the supposed heroes of the past. How do you view this?

I’ll answer by giving examples from my own family. The first bishop in the family was Johann Philipp Schönborn, who in the 1600s served as archbishop of Mainz and bishop of Würzburg, and later of Worms as well. Though baptized a Protestant, he oversaw three bishoprics. By virtue of being archbishop of Mainz, he was also an imperial elector and the imperial archchancellor, charged with overseeing the election of a new Holy Roman Emperor. What did it mean to be both a bishop and a territorial prince, a spiritual and a secular leader at the same time?

This Johann Philipp lived through the misery of the Thirty Years’ War, which decimated the population of Central Europe. On becoming archbishop and imperial chancellor in 1647, his most pressing concern was peace. He made decisive contributions to the Peace of Westphalia, which ended the war the following year. For this, he compromised with the Protestants – so much so that the papal nuncio in Germany, who later became Pope Alexander VII, criticized him for being overly conciliatory. But Johann Philipp, looking back on three decades of war, understood the great good of peace – and that for peace to last, the precondition was mutual tolerance.

Skalka Castle, birthplace and ancestral castle of Cardinal Schonborn (public domain)

Of course, today it’s easy to see the defects in the Peace of Westphalia, which enshrined the principle of cuius regio, eius religio – the ruler of a territory determines its religion. This principle not only created peace, but also resulted in mass expulsions: Protestants were driven from Catholic areas, Catholics from Protestant principalities, and Anabaptists were mistreated by everyone.

But ought we now to topple the statue of Johann Philipp because he created a partial peace for some people which brought much suffering to others?

Let me proceed to Johann Philipp’s nephew Lothar Franz Schönborn, archbishop of Mainz and bishop of Bamberg at the height of the Baroque era. Lothar Franz was also a politician of peace, a close friend of the Protestant philosopher and mathematician Leibniz, and a brilliant strategist who became the chief architect of his family’s great flowering. As a result of his efforts, one of his nephews, Friedrich Karl, became imperial vice chancellor and built the gigantic Baroque palace of Schönborn outside Vienna. For his services to the imperial house, the emperor gave him an unimaginably huge estate of 148,000 acres in what is today Ukraine. (It remained in the family until 1945, when Soviet troops expropriated it.)

Someday, people will ask: Why didn’t you see that within three generations you consumed all the petroleum that took millions of years to create?

Yet as bishops, these Baroque princes were also incredibly active pastors. After serving twenty-nine years as imperial vice chancellor, Friedrich Karl likewise became bishop of Würzburg. During his administration, 156 churches were either newly constructed or renovated. He was able to keep his province out of war and made possible a period of unheard-of prosperity. In his personal life, he was a model of piety.

And so I wonder: Where are the blind spots of our era? Someday, people will ask: Why didn’t you see that within three generations you consumed all the petroleum that took millions of years to create? Why didn’t you foresee the terrible consequences for humankind of the destruction of the world’s great forests? The difficulty is that we stand in a concrete moment in history and are unable to act as if it were two hundred years later.

You also inherited difficulties in your immediate family. Your father, a courageous opponent of National Socialism, later divorced your mother. How do you deal with your parents’ failings?

When my parents married during World War II, society had already undergone a drastic change following the fall of the European monarchies in 1918. However, their marriage was still socially problematic because my father came from the high nobility and my mother from the lower aristocracy – and besides that, she had a Jewish grandfather.

My parents met during the war; my father was serving on the front. They barely knew each other and never had time to build a life together – I think he simply wanted to have someone at home. In 1944, toward the end of the war, my father deserted to the English and then returned to Germany with the British army. He and my mother didn’t find each other again until after the war. It doesn’t surprise me that their marriage didn’t work out.

So although I was brought up in a deeply Catholic home, I had to learn early on that life sometimes plays out in less-than-ideal ways. Dealing with failure is one of the most important themes of history: one’s own personal and family history as well as the history of all humankind. According to the first pages of the Bible, human history began with a disaster! And that story continues. But I also sensed early on that this drama of imperfection is not the last word. I often heard my mother say, “God writes straight on crooked lines.”

Why is it important to you to know your identity as belonging to a particular family?

Despite my parents’ divorce, the family has been a real home for me, and I think for my siblings as well. That’s because family is more than just the parents. We were lucky to have a large extended family. What does “belonging to a family” mean? One of the greatest afflictions of our child-poor society is the lack of family networks. Loneliness can be oppressive if no family is to be found. Surprisingly enough, even in a damaged condition the family is a survival network. The family is not an ideal, yet there is nothing better. The family is affected by our sins and failings. At the same time, it is the place where we are at home and learn our first lessons in socialization. You can see it even in a refugee family like ours, with no permanent home and forced to live in many places during the first postwar years.

You were still quite young when you felt called to a celibate life. Today, do you miss having children of your own – biological heirs?

For me, the choice was clear: I was called to become a priest. In the Roman Catholic tradition, that meant forgoing a family of my own, but not forgoing my extended family – I have fifteen grandnieces and nephews.

One question does concern me personally: Would I have been a more mature person had I married and had children? Yet I can also say that I have had a very intense life up to now, with many marvelous encounters and the availability to help others.

Cardinal Schönborn’s parents at their wedding in Prague, 1942

There is a reason the celibate life exists and there is a model for it: the life of Jesus. I often ask him, “How did you live your life? You were a strong man” – one can sense that – “and you were a real man! You had marvelous interactions with women. You loved children; they were strongly attracted to you. But you had no wife, no children of your own. How did you manage that?” As yet, I haven’t had a clear answer from him. I also ask him: “You were a man with a man’s sexuality. How did you live with that?” And he did live with it.

There’s one thing you cannot say about Jesus, namely, that he was incapable of forming relationships. The Gospels are witness to wonderful encounters: “Woman, why do you weep?” – his first words upon rising from the dead addressed to Mary Magdalene. And his words to the widow of Nain with her dead son, her only son. What compassion! Jesus was and is a man with a wonderful capacity to relate to others.

Do you have spiritual heirs? Are there people who have worked with you or been your students and who are a sort of spiritual children?

I experienced that feeling very strongly with my students when I was a professor. I loved working with them and watching them develop. It was wonderful! There were always people I accompanied as a spiritual director, some of them through the course of many years. And there are marvelous spiritual friendships. That is something very precious indeed.

Still, I have to admit: when I hear a newly minted grandfather talk with shining eyes about the first time he held his newborn grandchild – that is something I will never experience.

It’s a paradox: today, interest in heredity and genealogy is booming – it has even given rise to an internet industry worth billions of dollars. Modern people, it seems, long for a sense of identity. Yet this is at odds with a central dogma of modern liberalism: that we can each invent ourselves just as we like.

A tree cannot stand without its roots, and neither can a human being. I often ask young people if they know the names of their great-grandparents, and what they were like. In my father’s family, we have a family tree that reaches back into the thirteenth century; on my mother’s side, it’s only into the seventeenth. I admire Jewish families who can say they are from the tribe of Levi. That’s three thousand years of genealogy!

To atone and ask forgiveness, the healing of memory, is a real task. The demons of hatred, pride, and nationalism must be banished.

The science of genetics has given us something simple to consider: all of us carry our ancestors in our bodies. They are all there. My genetic code is the inheritance of all my ancestors. And we carry within us an eternal soul that is not the product of our parents, not the product of our genealogy, but God’s creation. I am a human being, interwoven with the universe, the cosmos, and all human history. And yet, I am unmistakably unique, an individual created by God.

What, if anything, do we owe our ancestors?

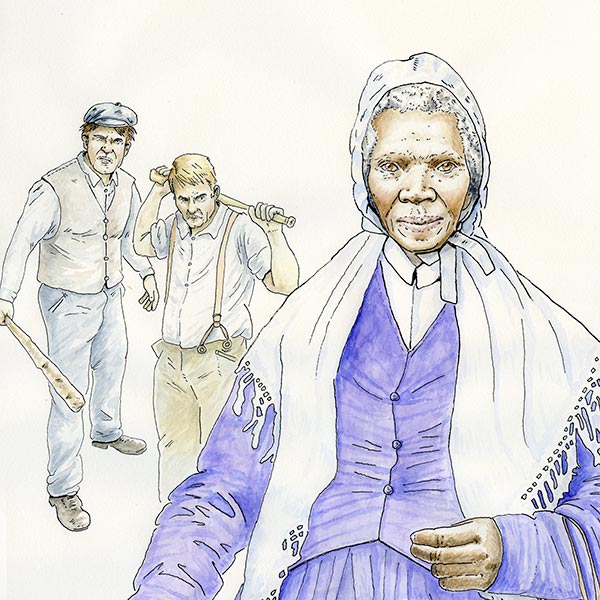

We owe our genetic inheritance to them. I carry within me my maternal grandfather’s colorblindness, inherited according to Mendelian laws. Do we also carry within us the guilt of our ancestors? There is no such thing as collective guilt, genealogical guilt. But there is a sense in which we are entangled in a history of guilt. My mother always told us that our inherited estate in Bohemia, which was very large, came to our family as a result of the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, in which the Bohemian nobility was defeated and partially wiped out. The Holy Roman Emperor rewarded the loyal victors with Bohemian estates. Three centuries later, my family’s expulsion from Bohemia after World War II was the endpoint of this painful history.

Even if I don’t believe there is such a thing as inherited guilt, we can still assume responsibility for our ancestors’ guilt. We assume it precisely because of our faith – by admitting that yes, our ancestors sinned. And we can atone for it and ask for forgiveness. Such paths of healing are important. The Czechs attempted to do just that with the Germans expelled in 1945. To atone and ask forgiveness, the healing of memory, is a real task. The demons of hatred, pride, and nationalism must be banished.

How does that apply to Christians and the Christian church, especially in overcoming our history of hatred and schism?

Once, at an ecumenical reception, I remarked that perhaps much of our ecumenical reconciliation within Christianity has to do with the fact that we were deprived of our power. No longer are we the seventeenth-century Protestant and Catholic states that went to war with each other, nor does the pope rule over an ecclesiastical state that wages wars. We live in secular countries. As far as issues of power are concerned, we are marginalized, which is probably also a blessing.

We must remember that Christians have often been persecuted, and still are today. It’s interesting that historically our opponents made no distinctions among the various confessions. Christians helped one another in the concentration camps and the gulag; they were all simply Christians. We had to become powerless to surrender ourselves to Christ’s power and put our trust in him – not in weaponry, not in political power, but “in demonstration of the Spirit and of power,” as Paul says (1 Cor. 2). The lovely thing is that we recognize one another anew, not from the standpoint of our confessions, but with a view to Christ. Whenever I encounter a brother or sister and I see that they really love the Lord, then there is an immediate basis for communication.

Cardinal Schönborn visits the new Bruderhof community in Retz, Austria (spring 2020). Photograph courtesy of Andrew Zimmerman

Of course, there are still enormous differences between confessions – in how we worship, for instance – but we know that the center is the same, the center is Christ. As Pope Benedict XVI told us, “What is meant by ecumenism? Simply this: that we listen to one another and learn from one another what it means to be a Christian today.” We experience that concretely when I encounter my dear friends in the Bruderhof community and how you live your Christianity! I’ve learned much from that.

As a Bruderhof member who moved to Austria last year, I’ve experienced firsthand this practical work for reconciliation – not least, through your welcome and support as we start a Bruderhof community here. What does this founding of a new Austrian Bruderhof mean to you?

It is a concrete example of the healing process, since of course the Anabaptist movement, to which the Bruderhof belongs, began here in Austria and neighboring countries five hundred years ago. When Bruderhof members visit the sites of the original Anabaptist communities in Moravia, it inevitably reminds us of how the Anabaptists were driven from their homes under the Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa. One might say that this expulsion simply reflected the politics of that time. But it also reflected a particular idea of how Christianity and the state should work together. There is a lesson here for us today.

And even now, although we as Catholics and Anabaptists can relate to one another so easily, that doesn’t mean that we’ve already done everything necessary. We must remember our history; we must talk about it with one another. How do you remember, and how do we? What wounds are still open? What burdens from the past still encumber us? That is the healing of memory that we must carry out simply by talking about our history. But the work of healing itself is the work of the Lord.

You’ve spoken often of your concern about the demographic trends in Europe toward a “childless or child-poor society.” What hope do you have for the future of the family?

Every child who is born brings hope. I believe that in his marvelous plan of creation and the creation of man and woman, the Creator gave us a clear sign of the path to follow, whatever course society may take. There were and still are all sorts of experiments like the ones undertaken by the Soviets, who separated children from their parents at an early age. We carry within us an eternal soul that is not the product of our parents, nor the product of our genealogy, but God’s creation.But a young man falls in love with a young woman. They begin life’s journey together, get married, and have children. The family is a wonderful network, stronger than any other. I have the greatest confidence in the Creator. We disturbed and abused creation through our sins, and that made a Savior necessary. And God sent us a Savior! Thank the Lord! The Creator laid out the basic pattern, and even after the Fall, he was always there. That is why I simply cannot be pessimistic about the future of the family.

This interview from September 12, 2020, has been edited for clarity and concision. Translation by David Dollenmayer.