Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Editors Picks Issue 21

-

Working Girls

-

Was Martin Luther King a Socialist?

-

Gustav Landauer

-

I Begin with a Little Girl’s Hair

-

Kochel: Waterfall I

-

Covering the Cover

-

Anabaptist Readings on Community of Goods

-

The Economics of Love

-

Readers Respond: Issue 21

-

Family and Friends Issue 21

-

The Bronx Agrarian

-

The McDonald's Test

-

What Lies Beyond Capitalism?

-

The Interim God

-

Robin Hood Economics

-

Is Christian Business an Oxymoron?

-

Not So Simple

-

Comrade Ruskin

-

An Excerpt from The Heart’s Necessities

-

Exposed

Who Owns a River?

Five Hundred Miles by Raft with a Floating Colony of Friends

By Christian Woodard

July 5, 2019

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

From where I sculled in the flatwater above rapids called, ominously, the Big Drops, I watched the rafts ahead of me – first one, then another, then a third – hit a big breaking wave and flip. I had heard that river guides called the wave Satan’s Gut. Or, more fitting, given that I was at the end of a month-long river trip before my wedding: the Mother-in-Law.

The Green River, like nearly every other American desert river, is dammed for irrigation, electricity production, and water storage. For five hundred miles, though, it flows unchecked from the north to the south of Utah. From Flaming Gorge Dam, the river cuts through the Uinta Mountains, curves into Colorado and back to Utah, bisects the Tavaputs Plateau, threads the three volcanic ranges of southern Utah – the La Sals, Abajos, and Henrys – and finally becomes Lake Powell on the border of Arizona. It is the country’s longest undammed wilderness waterway outside of Alaska, and in March 2017, a group of friends and I set out to row the whole thing.

While the water flows freely, the adjacent lands are broken into parcels, and the river’s uses are decided by whoever owns the surrounding land: wildlife refuges and management areas, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), national recreation areas, Dinosaur National Monument, Canyonlands National Park, and native reservations. These managers each treat the river differently – as a national treasure, irrigation source, and sewage disposal, to name a few of its uses.

Below the Gates of Lodore Photograph by Kari Nielsen

Because each agency issues permits only for its own section, running the whole Green is not as simple as driving to the put-in and shoving off. Occasionally, people row long stretches of the river, but we personally knew only one who went the whole way: Ken Sleight, the model for one of the characters in Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang. He did it before modern permitting, as a last visit to Glen Canyon before Lake Powell flooded it, in 1965.

Part of our intention was, like Sleight’s, to understand the watershed’s living continuity, linking the necessary permits and floating straight through, top to bottom. We wanted to see if land classifications really defined the river’s growth from clear mountain stream to silty behemoth.

By the time we pushed off at Flaming Gorge Dam, a new administration in Washington had begun reviewing federal control of southwestern public lands – most controversially, reconsidering the status and size of Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah. While the politicians argued, we set out to visit for ourselves the oil and grazing leases, the granaries and the pictographs.

The trip was also a chance to watch winter turn to spring and geese hatch their eggs, to see the river move from ponderosa to juniper to sage and cut through the layers of ancient seas and dunes and deltas. The plan was to share these changes with a changing group of friends, making art and dinner, and believing that no matter what the politicians decided, human systems can live respectfully with nature.

And the trip was a month-long bachelor and bachelorette party for my fiancée, Kari, and me, bringing together friends from every corner of our lives. According to the plan, Kari and I would row to the takeout, de-rig, and get married two days later. The plan did not include three upended rafts and eleven of our closest friends swimming through Satan’s Gut.

When John Wesley Powell set out to navigate the Green River in 1869, there were no permits, no land managers, and no reliable maps. Some traveling herders, a few Mormon settlers, and tribes like the Uintah and Ouray Utes were the region’s only inhabitants. But the eastern United States was filling up and Americans were enthusiastic for homestead claims. The General Land Office, eager to open another frontier to cultivation, was hungry for any information on the unknown territory.

Powell was a willing, though questionably fit, leader for that exploration. Born in 1834 in western New York, he was the son of a preacher who moved his family many times before settling in Illinois. As a young man, Powell taught school in rural Illinois, and despite seven years spent at Illinois College, the Illinois Institute (today’s Wheaton College), and Oberlin College, never obtained a degree. He liked long-distance trips. By age twenty-five he had walked four months across Wisconsin, rowed the whole Mississippi, the whole Ohio, and down the Illinois River and upstream into the Des Moines. Those trips interested him in watershed connectivity – and given his dogged personality, he may eventually have explored every Mississippi tributary.

According to the plan, Kari and I would row to the takeout, de-rig, and get married two days later.

But the war came. In May 1861, just weeks after Fort Sumter, Powell enlisted in the Illinois infantry, soon absorbed into the Union Army. At Shiloh a year later, he lost his right arm below the elbow. Despite the disability, he returned to the Army and remained in active service until early 1865. After the war, Major Powell – still without a degree, but with some martial prestige – lectured at Illinois Wesleyan University and curated a natural history museum. On one of his collecting trips to the headwaters of the Green, his old source-to-sea urges returned. In the national mood of post-war expansionism Powell saw an opportunity for government support.

He went to Congress in 1868 – a one-armed boatman with no whitewater experience or formal cartographic training – and proposed to navigate and map the whole Green and Colorado Rivers. Congress, seemingly unimpressed, offered no funding but authorized Powell to draw rations from any Army posts he found along his journey. The Smithsonian supplied scientific instruments, and Powell cobbled together support from a handful of other private sources, including his own salary as a university lecturer.

On this tenuous footing, Powell and ten men left Green River, Wyoming, on May 24, 1869. They hoped to float more than 1,100 unknown miles, south through Flaming Gorge and Glen Canyon – both of which are today flooded by reservoirs – and west along the Grand Canyon. Three months later, Powell emerged at Grand Wash Cliffs. One man had left early in the trip; three others hiked out shortly before the journey’s end, never to be seen again. Rapids had claimed the group’s scientific instruments, their geological samples, and one of their boats. They had drawn no maps. But they had fulfilled the contract’s more glorious half: the first complete descent of the Green and Colorado Rivers.

Haggard and heroic, Powell presented a preliminary report to Congress. The arid region, he said, would not support agriculture the way Americans practiced it. If the Land Office (predecessor of today’s Bureau of Land Management) distributed its customary square sections, a few barons would control all the water. He suggested, instead, parcels based on topography, allowing each claimant access to surface water. He even proposed that political boundaries nest inside watersheds, so that each state, county, town, and “colony” – Powell’s preferred term for the kind of cooperative settlements he recommended – administered its own water resources.

Then, as now, Powell’s recommendation sounded like a fringe, anti-progress delusion. The Land Office listened politely to his advice, but went on to survey the dry, mountainous region as if it were Iowa. A century and a half later, we have dammed and diverted not just the Green but most Western rivers to develop desert cities. Instead of the communal sensibilities Powell advised, we have chosen intricate compacts and trades, incapable of apportioning a shrinking water supply. People are ready to fight for their water, their cultural heritage, and their square property lines.

Like Powell, I was raised in western New York in a Wesleyan family. Long before seeing the American Southwest, I had read about the Semitic tribes of Genesis, who traveled between grass and water. By the time Powell reached the Southwest, some white herders were living a similar, semi-nomadic life. He described them in his 1878 Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States: “people who are already in the country and who have herds with which they roam about seeking water and grass, and making no permanent residences.”

Melake and Eyal share Ethiopian Lent food. Photograph by Kari Nielsen

These people had left civilization’s captivity to return to transient, subsistence life – like the Hebrews of the Exodus, whose “wandering in the wilderness” is recorded in Numbers 33 as a series of points linked by travel. It is a curvilinear journey through which the Hebrews mold themselves to the demands of the land and cement their tribal society. One example reads: “They set out from Marah and came to Elim; at Elim there were twelve springs of water and seventy palm trees, and they camped there. And they set out from Elim and camped by the Red Sea. And they set out from the Red Sea and camped in the wilderness of Sin.”

It sounds a lot like a log of our river trip: “Camped in Brown’s Park. Found a dead elk tangled in barbed wire around a Wilderness Study Area. Left Brown’s Park. Rowed toward the Uintas, camped on river left.” It is also characteristic of Mormon pioneer journals, and of the patterns of overlapping indigenous groups who lived along the Green before its division into refuges and reservations, monuments and parks. One of our friends on the trip, a cartographer, calls accounts like this “networks” – a way of conceptualizing land that prioritizes movement and answers the question How do I get there from here?

Yet if the American desert was to be made a Promised Land, as the Mormons and the Land Office both envisioned in their own ways, it needed a new settlement model. When the Hebrews cross the Jordan into Canaan, they pitch their geographic language in a new way:

When you enter the land of Canaan (this is land that shall fall to you for an inheritance, the land of Canaan, defined by its boundaries), your south sector shall extend from the wilderness of Zin along the side of Edom. Your southern boundary shall begin from the end of the Dead Sea on the east; your boundary shall turn south of the ascent of Akrabbim. …

And so on for eight verses until the region has been outlined with an imaginary surveyor’s transit: “… and its end shall be at the Dead Sea. This shall be your land with its boundaries all around.” The land is no longer linked by pathways; it is divided into parcels. A map like this prioritizes permanence and resource use, and answers the question Who owns what?

Network maps – of rivers, trails, or stars – show up in non-agrarian societies, whether they hunt, fish, herd, or gather for subsistence. Property maps belong to settled, agrarian societies.

For the first explorers of the interior West and their indigenous forebears, the land’s aridity, soil, grade, and aspect were ultimate authorities. But the link between human and natural systems was broken by the same thinking that treated the Jordan as an edge instead of the heart of a valley. After one hundred and fifty years of agrarian experimentation in the arid region, the networks are all but buried under legalities and property boundaries. On our trip, we hoped to find hints of the lost pathways, letting our habits grow with the requirements of the river.

While many river-runners have dreamed of a long Green River trip, the journey was especially significant for Kari and me. One of our first dates had been a canoe trip on the Green. A few years later, I had proposed to her in a slot canyon near the river. We had made some of our best friends on different sections of the Green, and connecting the whole river would bring us and our friends together for the wedding.

On March 15, 2017, a little less than one hundred and fifty years after Powell started his expedition, six of us packed boats at Flaming Gorge Dam, near the Wyoming border. Kari’s sister, Lindsey, stowed bags of dried food with her best friend, Rachel. Ryann, a raft guide who had helped Ken Sleight edit his memoirs, pumped the raft tubes. Kari adjusted the canoe’s sprayskirt with Pete, a biologist from Salt Lake. I chatted with some fishermen.

Ryann Savino pulls into the Uinta Basin. Photograph by Kari Nielsen

Most of us had been down the Grand Canyon or other parts of the watershed together. Ten years earlier, Pete and I had retraced a historic canoe route across Nunavut. Lindsey and Rachel had been kayak guides in Southeast Alaska and Baja. We were all familiar enough with long trips to respect the moment of shoving off. We had planned everything carefully, but once we were underway the rendezvous points, food drops, and shuttles would be set in stone. Untying the boats meant committing to bring everyone through safely and to arrive on time, not only at each of the four bridges that cross the Green on its five-hundred-mile descent, but to our own wedding, exactly one month away. Snow hung on the shady ridges, and Flaming Gorge Dam released two thousand cubic feet per second of clear, green water, headed for Lake Powell. We bobbed at the end of the ropes for a minute, then cast off into the current.

The trip’s first addition came three days later, at the Dinosaur National Monument checkpoint. We traded Pete for Eyal, who had taken his first raft trip with Kari and me less than a year before. He had loved all of it – whitewater, long conversations, good food, and the rhythm of waking up each morning on the river. He had signed on for our Green River trip without hesitation, excited to row every rapid despite his inexperience. Others would come and go at each bridge, but the six of us would make the whole rest of the trip. We grilled dinner and watched the river pour into a quartzite hallway that Powell’s group had named the Gates of Lodore.

In 1966, the Bureau of Reclamation proposed a project to flood the Gates of Lodore. The Sierra Club and Wilderness Society, arguing that national monuments should be exempt from development, successfully opposed the plan. Partially because of that precedent, modern developers are wary of new monument designations.

In the morning, a ranger equipped with a bulletproof vest, pistol, Taser, pepper spray, and very thorough checklist met us at the rafts. Eyal, who has both a congenital and a conditioned distrust of law enforcement, retreated to the farthest raft and crossed his arms. The ranger asked what we planned to do with our poop. We told him we would pack it out in ammo cans.

He asked what day we intended to pass the Yampa confluence, the only other road access inside Dinosaur National Monument. We told him March 20.

He asked how many pulleys we had. None. No, maybe two? Carabiners work fine. How many are we supposed to have?

He was just checking. They were not required. Have a nice trip.

Eyal shoved us off with slightly more gusto than necessary. We rowed into the Gates, where Powell’s expedition had pinned a boat on a rock. Maybe if they had had pulleys, they could have saved it.

Twenty days in, it was feeling normal to wake up covered in sand.

Three days later, we floated under the towering, overhung fin of Weber sandstone that marks the Yampa confluence. The same ranger stood on the beach, hands on his gun belt, elbows out. I waved, Eyal scowled, and the ranger shook his head ambiguously. We kept on through Whirlpool and Split Mountain Canyons, stopping to soak in a tepid hot spring.

We floated out of Dinosaur and the high, snowbound Uinta plateau came into relief. We were entering the forgotten heart of the Green: the Uinta Basin. Surrounded by a patchwork of private and state land, a wildlife refuge, and fragments of Uintah and Ouray Reservation, it sees less attention from scientists and land managers than any other section of the river. While seventeen thousand people float through Dinosaur every year, the hundred miles of flatwater just downstream are nearly deserted.

Ironically, when Powell set out, the Uinta Basin was the only mapped section of the river. Soon after he pushed off, his expedition was rumored lost, and settlers in the basin watched for broken boats and bodies. A month later, Powell’s group coasted into known territory, where they sent letters home, resupplied (per their congressional mandate) at the only Army post they would encounter, and got sick on potato greens from a homesteader’s garden. It was to be their last taste of civilization until they emerged from the Grand Canyon three months later.

In the intervening century and a half, the known and unknown territories of the Green have exactly reversed. The wild water and inescapable walls that intimidated Powell’s men have become the river-runner’s back yard. Many river guides have spent their careers on the Green without dipping an oar in the Uinta Basin.

So as we floated south we felt some of the exploratory thrill that charged Powell’s trip. There were no new canyons to name but everything sparkled under the light of discovery. Ryann pulled over to pee and found a goose nest with six eggs. Lindsey drew cranes and pelicans wheeling over freshly planted fields. We collected driftwood and willows and made our campfires where the cows came down to drink. We fought headwinds and pushed through miles of deadwater, thick with fertilizer foam. One afternoon we passed a bluff covered in cowboy petroglyphs – brands and spurs, horses and names pecked into the rock. We slept under crackling high-tension lines, and with the hinge and beat of scattered oil rigs.

Just upstream of the Ouray bridge, we picked up another friend and slept across the road from a pumping station. At intervals, tanker trucks geared down into the lot, took on river water, and went back out into the night.

From Sand Wash, where the Tavaputs Plateau rises around the river in gray cliffs, the Green flows through Desolation and Gray Canyons, eighty-three miles of easy whitewater. We checked in with the Bureau of Land Management, which oversees the right bank of the river, and verified our permit to camp on Ute land, river left.

While the tribe and the BLM hold the majority of the land on the Tavaputs, there are a few private inholdings, including the Rock Creek Ranch, homesteaded in 1914 but now falling to ruin. When we pulled up, the unpruned apple and apricot trees were blooming, and Rock Creek poured snowmelt into the river. Roofless sandstone buildings held relics too heavy or useless to lug back to civilization – a cast-iron stove, a weather-curled boot, some carefully stacked patches of window screen.

Goose eggs photograph by Kari Nielsen

Powell’s 1878 report suggested that groups of settlers could share these fertile bottomlands, supporting each other through the inevitable droughts, hard winters, and remoteness of high desert homesteading. “The pasturage farms cannot be fenced – they must be occupied in common,” he said. “These lands could be settled and improved by the ‘colony’ plan better than by any other. … Customs are forming and regulations are being made by common consent among the people in some districts already.” The setting, he thought, demanded cooperation and communal accountability.

America, though, was high on individualism, technological progress, and frontier optimism. Claimants like the Rock Creek Ranch staked springs and streams controlling thousands of surrounding acres, fenced out competitors, and shortly went bankrupt. Some unwanted land was allotted to native groups, and the Bureau of Land Management got the rest. Today, the BLM manages over two-thirds of Utah’s land.

Into this landscape, which Wallace Stegner called “the most spectacular and humanly the least usable of all our regions,” we brought our own small colony. By that point, Lindsey had used up a handful of pens on her daily ink drawings. Kari and I had gotten violently ill by eating a cactus. Ryann had read aloud her favorite desert writers over watercress- and nettle-topped pan pizzas. Eyal was teaching us the Hebrew alphabet. We wanted not to “use” the land, but to cultivate a strong community in reference to it. Faith in human wisdom and dignity recognizes those characteristics in the surrounding landscape. It allows natural systems their own power, not as resources, but as home. Twenty days in, it was feeling normal to wake up covered in sand.

In Green River State Park, three hundred miles from our starting point, we ate cinnamon rolls and took long showers. We picked up ten more friends, three rafts, and a whitewater canoe. Ken Sleight and his wife, Jane – and their goat, Rosa – drove from Moab to see us off on the last stretch before our wedding. We planned to float through Labyrinth, Stillwater, and Cataract Canyons, taking out at the Dirty Devil River, where Ken used to start his favorite trips, through Glen Canyon.

In the late 1950s, Ken helped pioneer Glen Canyon rafting. He advertised two-week floats with military surplus rafts, which he carried to the river by mule train. In the old pictures, he’s a skinny man with big ears and a big smile. A caricature of that young river guide became “Seldom Seen Smith” in The Monkey Wrench Gang, Edward Abbey’s 1975 novel of sabotage and environmental protest. Seldom Seen is an elusive, fiery character, equally at home on a river trip or obstructing land development. He cuts fence and disables machinery. He has forsaken Mormonism, but still prays. In one scene he kneels on Glen Canyon Dam, beseeching the Lord to destroy the offending structure with a “precision-type earthquake.”

Fremont petroglyphs, Jones Hole. Photograph by Kari Nielsen

Ken, also raised Mormon, has protested the dam from the beginning, founding several eco-defense groups and successfully suing the federal government in 1970. He has been a fervent voice in southwestern water and environmental debates. Despite Ken’s similarities to Seldom Seen, Abbey never identified his longtime friend as the character’s model.

Now eighty-eight, Ken still has the big smile, and slightly bigger ears. More than fifty years after the Bureau of Reclamation flooded Glen Canyon and rebranded it Lake Powell, after its first surveyor, Ken still calls it “Lake Foul.” Ken asked us if the Uinta Basin had been windy. It had. He nodded. It’s always windy up there. He tapped on Ryann’s raft, checking the tubes for pressure. He nodded again, and wished us luck in Cataract. We all watched Rosa the goat poke her nose into the river and snatch it back.

The water was brown and cold. Spring melt was coming into its own, and below the Colorado confluence the river was forecast to reach thirty-five thousand cubic feet per second. In high water, Cataract is one of the most difficult sections of the river. Even the Grand Canyon, just downstream but now regulated by Glen Canyon Dam, rarely equals its volume and gradient.

Ken and Jane – and Rosa the goat – headed back to Moab, and we pushed off for the smooth sandstone of Canyonlands National Park. It would take us another week to follow the river into deeply cut dune formations, then through delta deposits with chunks of petrified wood, the hard White Rim, a series of sandstones and shales, and after the confluence with the Colorado, into the faulted complex of shallow sea sediments that form Cataract Canyon’s whitewater.

We camped downstream from the confluence on a broad sand bench, circled by clifftop needles and spires. The last sunlight came through the rocks and a nearly full moon rose across the river. Far upstream, we heard the voices of our final group of friends, rowing down the Colorado to meet us. From the original group of six, we had grown to twenty-one boisterous friends, happy to be back on the water together.

The next day we all climbed to the rim to see Cataract’s first rapids roll around a corner. Past that bend, the river makes the western boundary of the Abajo Mountains, Dark Canyon, and Cedar Mesa, now under review as federal officials debate the future of the vast Bears Ears National Monument. The granaries and dwellings in those cliffs have been inhabited, abandoned, and re-inhabited for five thousand years. Clovis points from the area could be more than twice as old.

The fight over Bears Ears involves questions about whether the cultural history and the natural integrity of land within the monument are compatible with cattle ranching, oil and gas extraction, and the high-volume tourism that land protection invites. But these cultural and eco-regions stretch beyond Bears Ears into the plateau’s headwaters – southern Wyoming, western Colorado, and northern Arizona and New Mexico. We had seen pictographs and petroglyphs from the very top of our journey, and if the man-made Lake Powell had not covered them with its water, we would have seen more downstream. The entire Colorado Plateau is linked by its waterways and the traditional routes of its inhabitants.

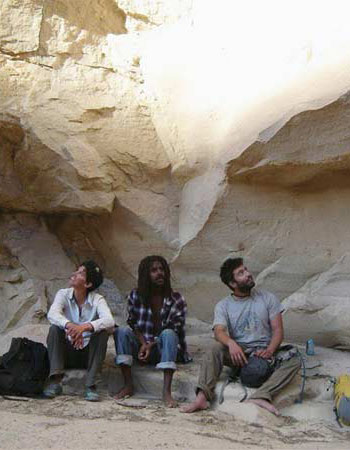

Kari, Melake, and Eyal near the end of Gray Canyon. Photograph by Christian Woodard

Should we protect Bears Ears? Should we regret flooding Glen Canyon or saving Dinosaur? Can we accept our role in transforming a once-living landscape into a set of resources to be exploited? These questions are inevitably political. But they are spiritual and moral, too, no matter how ill-equipped we are to recognize and discuss them in that way.

It is impossible to know whether Powell would have approved of the extractive morality that his surveys enabled. He certainly would not have been surprised. After his shoestring first descent, Powell returned to the Green and Colorado Rivers for a government-funded survey in 1871 to 1872. His maps became the basis for the fledgling United States Geological Survey, which he directed for more than a decade.

In 1879, frustrated by the Land Office’s disregard for his recommendations for limited, communal settlement of the arid region, Powell tried a new tack. With the Smithsonian’s support, he founded the Bureau of American Ethnology to research native languages and traditions that the surveys had already begun to displace. After a career in empirical, physical geography, Powell came to believe that the land we inhabit is shaped by the stories we tell.

It has taken more than a century of development, but interest is growing in Powell’s ethnographic work and its embedded, land-centric morality. Of course, our inherited stories are not going away: Moses taking off his sandals, or striking water from the rock. The straight-line boundaries of the Promised Land. Ken Sleight, rowing through Glen Canyon’s smooth meanders for the last time. Little by little, we are finding ways to integrate those stories and add some of our own – from a first date to a complete descent with a floating colony, preparing for our wedding by living closely with the river.

Storm in Rainbow Park. Photograph by Kari Nielsen

We spent the day on the rim, climbing strange rocks. In the afternoon, we came down to help Eyal prepare a Passover seder. We collected bitter herbs and kept a fire under the lamb. By now, we were all familiar with the currents of one another’s moods and gestures. We stayed up late discussing our wanderings, drinking wine, and watching the moon cross from one rim to the other. Like Powell, we had come to believe in self-organizing systems, in which respect for community and for the continuity of the land can reinforce one another.

The next morning, I looked down the tongue of the Big Drop to see three rafts upside down in the foam. Just when things seemed most in hand, we were still at the mercy of the water. I dipped my oars to face the rising wave, and rowed.

Map by Benjamin Meader. Used with permission.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Bradford Pugh

I lived in Southern Idaho and Utah for 21 years and never floated the Green River below 12 Mile. But I spent so many amazing hours and days fly fishing from the Flaming Gorge tailgaters to 12 Mile. So rich and beautiful. I miss living in the west. Thank you for sharing the river with me. I read it like I was there.