Subtotal: $

Checkout-

The Interim God

-

Robin Hood Economics

-

Is Christian Business an Oxymoron?

-

Not So Simple

-

Comrade Ruskin

-

An Excerpt from The Heart’s Necessities

-

Exposed

-

Who Owns a River?

-

Editors Picks Issue 21

-

Working Girls

-

Was Martin Luther King a Socialist?

-

Gustav Landauer

-

I Begin with a Little Girl’s Hair

-

Kochel: Waterfall I

-

Covering the Cover

-

Anabaptist Readings on Community of Goods

-

The Economics of Love

-

Readers Respond: Issue 21

-

Family and Friends Issue 21

-

The Bronx Agrarian

-

The McDonald's Test

Capitalism can’t be reconciled with the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth – or so claims the New Testament translator David Bentley Hart. Christ condemned not just greed for riches, but their very possession, and Jesus’ first followers were voluntary communists. With technologized market forces dominating our world, is a truly Christian economics still possible? What, if anything, lies beyond capitalism?

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

I : What Is Capitalism?

“Commerce is, in its essence, satanic. Commerce is the repayment of what was loaned, it is the loan made with the stipulation: Pay me more than I give you.” —Baudelaire, Mon cœur mis à nu

I have no entirely satisfactory answer to the questions that prompt these reflections; but I do think the right approach to the answers can be glimpsed fairly clearly if we first take the time to define our terms. These days, after all, especially in America, the word capitalism has become a ridiculously capacious portmanteau word for every imaginable form of economic exchange, no matter how primitive or rudimentary. I take it, however, that here we are employing it somewhat more precisely, to indicate an epoch in the history of market economies that commenced in earnest only a few centuries ago. Capitalism, as many historians define it, is the set of financial conventions that took shape in the age of industrialization and that gradually supplanted the mercantilism of the previous era. As Proudhon defined it in 1861, it is a system in which as a general rule those whose work creates profits neither own the means of production nor enjoy the fruits of their labor.

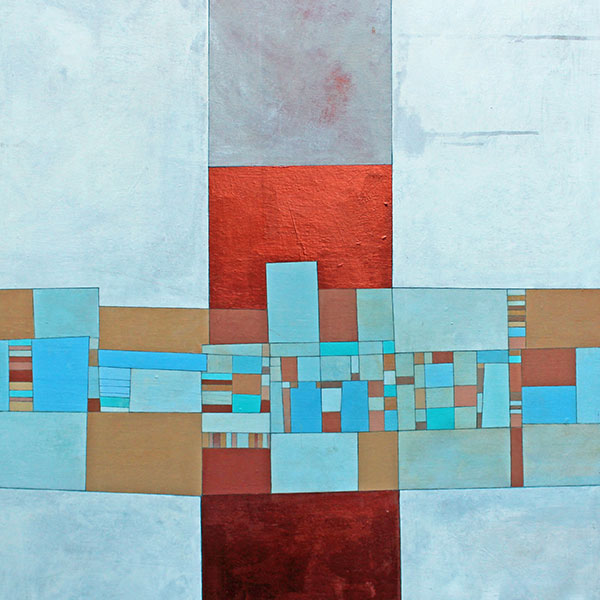

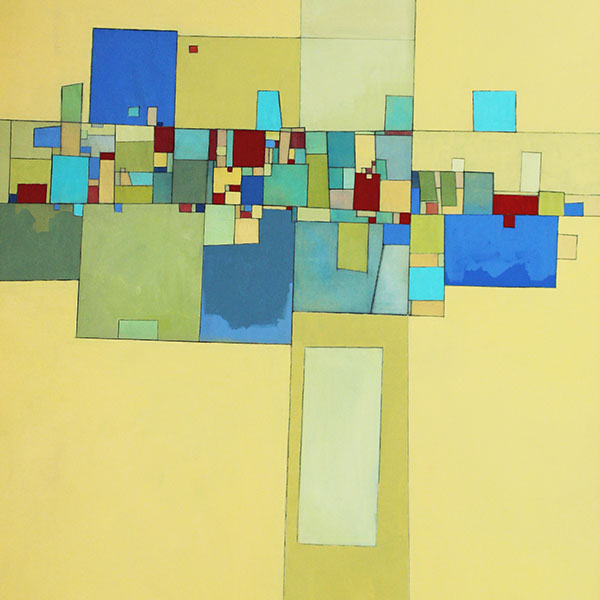

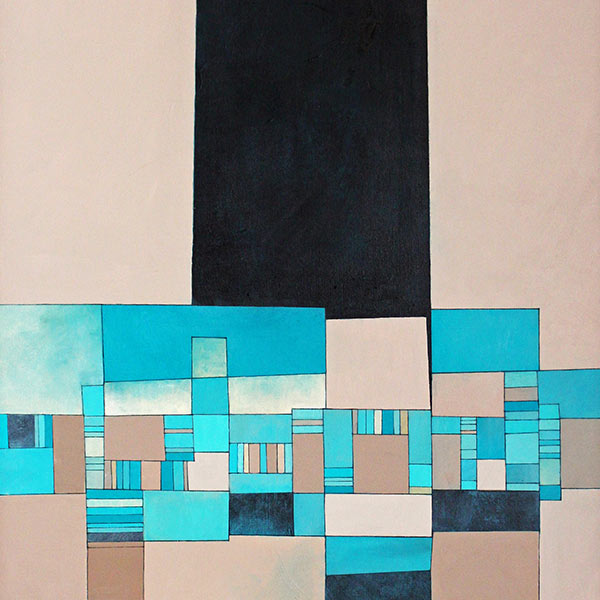

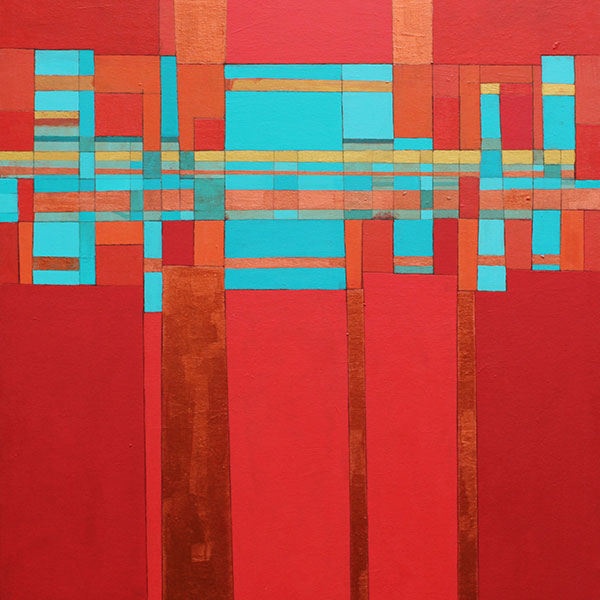

Deborah Batt, Rural Decay, detail All images used with permission

This form of commerce largely destroyed the contractual power of free skilled labor, killed off the artisanal guilds, and introduced instead a mass wage system that reduced labor to a negotiable commodity. In this way, it created a market for the exploitation of cheap and desperate laborers. It was also increasingly abetted by government policies that reduced the options of the disadvantaged to wage-slavery or total indigence (such as Britain’s enclosures of the commons starting in the middle of the eighteenth century). All of this, moreover, necessarily entailed a shift in economic eminence from the merchant class – purveyors of goods contracted from and produced by independent labor, subsidiary estates, or small local markets – to capitalist investors who both produce and sell their goods. And this, in the fullness of time, evolved into a fully realized corporate system that transformed the joint-stock companies of early modern trade into engines for generating immense capital at the secondary level of financial speculation: a purely financial market where wealth is created for and enjoyed by those who toil not, neither do they spin, but who instead engage in an incessant circulation of investment and divestment, as a kind of game of chance.

For this reason, capitalism might be said to have achieved its most perfect expression in the rise of the commercial corporation with limited liability, an institution that allows the game to be played in abstraction even from whether the businesses invested in ultimately succeed or fail. (One can profit just as much from the destruction of livelihoods as from their creation.) Such a corporation is a truly insidious entity: Before the law, it enjoys the status of a legal person – a legal privilege formerly granted only to “corporate” associations recognized as providing public goods, such as universities or monasteries – but under the law it is required to behave as the most despicable person imaginable. Almost everywhere in the capitalist world (in America, for instance, since the 1919 decision in Dodge v. Ford), a corporation of this sort is required to seek no end other than maximum gains for its shareholders; it is forbidden to allow any other consideration – say, a calculation of what constitutes decent or indecent profits, the welfare of laborers, charitable causes that might divert profits, or what have you – to hinder it in this pursuit.

The corporation is thus morally bound to amorality. And this whole system, obviously, not only allows for, but positively depends upon, immense concentrations of private capital and dispositive discretion over its use as unencumbered by regulations as possible. It also allows for the exploitation of material and human resources on an unprecedentedly massive scale. And, inevitably, it eventuates in a culture of consumerism, because it must cultivate a social habit of consumption extravagantly in excess of mere natural need or even (arguably) natural want. It is not enough to satisfy natural desires; a capitalist culture must ceaselessly seek to fabricate new desires, through appeals to what 1 John calls “the lust of the eyes.”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Deborah Batt, Urban Village, detail

The very least that one must concede is that capitalism “works.” That is, it produces enormous wealth, and adapts itself with remarkable plasticity to even the most abrupt changes of cultural and material circumstances. When it has faltered, here or there, it has evolved new mechanisms for preventing the same mistake from being made again. It does not bring about a just distribution of wealth, of course; nor could it. A capitalist society not only tolerates, but positively requires, the existence of a pauper class, not only as a reserve of labor value, but also because capitalism relies on a stable credit economy, and a credit economy requires a certain supply of perennial debtors whose poverty – through predatory lending and interest practices – can be converted into capital for their creditors. The perpetual insolvency of the working poor and lower-middle class is an inexhaustible font of profits for the institutions upon which the investment class depends.

One can also concede that, now and then, the immense returns reaped by the few can redound to the benefit of the many; but there is no fixed rule to that effect, and generally quite the opposite is the case. Capitalism can create and enrich or destroy and impoverish, as prudence warrants; it can encourage liberty and equity or abet tyranny and injustice, as necessity dictates. It has no natural attachment to the institutions of democratic or liberal freedom. It has no moral nature at all. It is a system that cannot be abused, but only practiced with greater or lesser efficiency. But, of course, viewed from any intelligible moral perspective, that which is beyond the distinction between good and evil is, in its essence, evil.

For all these reasons, it seems wise to me that we have elected to ask ourselves not what comes after capitalism, but rather what lies beyond it. As far as I can see, what comes after capitalism – that is, what follows from it in the natural course of things – is nothing. This is not because I believe that the triumph of the bourgeois corporatist market state constitutes the “end of history,” the final rational result of some inexorable material dialectic. Much less do I imagine that the logic of capitalism has won the future and that its reign is destined to be perpetual. In fact, I suspect that it is, in the long run, an unsustainable system.

My conviction is based, rather, on a very simple calculus of the disproportion between infinite appetite and finite resources. Of its nature, capitalism is a monstrously metastasized psychosis, one that will ultimately, if left to itself, reduce the whole of the natural order to a desert: despoiled, ravaged, poisoned, profaned. The whole planet is already immersed in an atmosphere of microplastic particles, wrapped in a thickening shroud of carbon emissions, whelmed in floods of heavy metals and toxins. And I have no expectation that any contrary impulse – say, the instinct of survival, a sane ethical consequentialism, a solicitude for nature, a spontaneous reverence for the glory of creation – will significantly impede its advance toward that inevitable terminus.

Essentially, capitalism is the process of securing evanescent material advantages through the permanent destruction of its own material basis. It is a system of total consumption, not simply in the commercial sense, but in the sense also that its necessary logic is the purest nihilism, a commitment to the transformation of concrete material plenitude into immaterial absolute value. I expect, therefore, that – barring the appearance, at an oblique angle, of some adventitious, countervailing agency – capitalism will not have exhausted its intrinsic energies until it has exhausted the world itself. That would, in fact, mark its final triumph: the total rendition of the last intractable residues of the merely intrinsically good into the impalpable Pythagorean eternity of market value. And any force capable of interrupting this process would have to come from beyond.

Deborah Batt, Community, detail

II : Beyond Capitalism

“We know that the Jews were prohibited from investigating the future…. This does not imply, however, that for the Jews the future turned into homogeneous, empty time. For every second of time was the strait gate through which Messiah might enter.” —Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Concept of History

The ultimate horizon of that “beyond,” to be honest, is not difficult to imagine. It is more or less the same thing that all sane rational wills long for, almost as a kind of transcendental: history’s sabbath, blissful anarchy, pure communism, a human and terrestrial reality where acquisitive desire can find nothing to fasten upon because nothing is withheld, and nothing delightful or useful is out of reach, and all things are shared by a community of rational love. Even the blithering neo-liberal naïf who believes in supply-side economics is, unbeknownst to himself, an anarcho-communist in his profoundest transcendental intentions; somewhere deep within him a little Pyotr Kropotkin sleeps and dreams of a world purged of greed and violence. Everyone longs for the terrestrial paradise, for Eden as the end of the story rather than as its irrecoverable beginning.

But Eden is not the dialectical issue of history, the final fruit of an occult rationality working itself out in and through the apparent contradictions of finitude. It is beyond in every sense. It inhabits time only as an eschatological judgment upon the present, a constant anamnesis of the good order of creation that we have always already betrayed. We know it principally as condemnation, and only secondarily as a sustaining hope. And how to translate that judgment into an agency immanent to history, one sufficiently powerful to disrupt the rule of capital before nothing remains to be saved, is the great question of all political thought of any real substance in the modern world.

Tell me, do you really seek riches and financial gain from the destitute? If this person had the resources to make you even wealthier, why did he come begging to your door? He came seeking an ally but found an enemy. He came seeking medicine, and stumbled onto poison. Though you have an obligation to remedy the poverty of someone like this, instead you increase the need, seeking a harvest from the desert.

Basil of Caesarea, “Against Those Who Lend at Interest”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

It is a question, moreover, that Christians cannot avoid. Admittedly, the social and institutional history of the church gives one little hope that very many Christians have ever been acutely conscious of this. But, whether or not they care to acknowledge the full implications of their faith, Christians are still obliged to affirm that this eschatological judgment has indeed already appeared within history, and in a very particular material, social, and political form. In many ways, John’s Gospel is especially troubling as regards the sheer inescapable immediacy of God’s verdict upon every worldly structure of sin. There eschatology becomes almost perfectly immanent. There Christ passes through history as a light that reveals all things for what they are; and it is our reaction to him – our ability or inability to recognize that light – that shows us ourselves. To have seen him is to have seen the Father, and so to reject him is to claim the devil as one’s father instead. Our hearts are laid bare, the deepest decisions of our secret selves are brought out into the open, and we are exposed for what we are – what we have made ourselves.

But it is not only John’s Gospel, really, that tells us as much. The grand eschatological allegory of Matthew 25, for instance, says it too. In John’s Gospel, one’s failure to recognize Christ as the true face of the Father, the one who comes from above, is one’s damnation, here and now. In Matthew’s, one’s failure to recognize the face of Christ – and therefore the face of God – in the abject and oppressed, the suffering and disenfranchised, is the revelation that one has chosen hell as one’s home. All our works, as Paul says, will be proved by fire; and those whose work fails the test can be saved only “as by fire.” Nor does the New Testament leave us in any doubt regarding the only political and social practices that can pass through that trial without being wholly consumed.

Whatever else capitalism may be, it is first and foremost a system for producing as much private wealth as possible by squandering as much as possible of humanity’s common inheritance of the goods of creation. But Christ condemned not only an unhealthy preoccupation with riches, but the getting and keeping of riches as such. The most obvious example of this, found in all three synoptic Gospels, is the story of the rich young ruler, and of Christ’s remark about the camel and the needle’s eye.

Deborah Batt, Dwelling 10, detail

But one can look anywhere in the Gospels for confirmation. Christ clearly means what he says when quoting the prophet: he has been anointed by God’s Spirit to preach good tidings to the poor (Luke 4:18). To the prosperous, the tidings he bears are decidedly grim: “Woe to you who are rich, for you are receiving your comfort in full; woe to you who are full fed, for you shall hunger; woe to you who are now laughing, for you shall mourn and weep” (Luke 6:24–25). As Abraham tells Dives in Hades, “You fully received your good things during your lifetime… so now you suffer” (Luke 16:25). Christ not only demands that we give freely to all who ask from us (Matt. 5:42), with such prodigality that one hand is ignorant of the other’s largesse (Matt. 6:3); he explicitly forbids storing up earthly wealth – not merely storing it up too obsessively – and allows instead only the hoarding of the treasures of heaven (Matt. 6:19–20). He tells all who would follow him to sell all their possessions and give the proceeds away as alms (Luke 12:33), and explicitly states that “every one of you who does not give up all that he himself possesses is incapable of being my disciple” (Luke 14:33). As Mary says, part of the saving promise of the gospel is that the Lord “has filled the hungry with good things and sent the rich away starving” (Luke 1:53). James, of course, says it most strikingly:

Come now, you who are rich, weep, howling at the miseries coming upon you; your riches are corrupted and moths have consumed your clothes; your gold and silver have corroded, and their rust will be a witness against you and will consume your flesh like fire. You have stored up treasure in the Last Days! See, the wages you have given so late to the laborers who have harvested your fields cry aloud, and the cries of those who have harvested your fields have entered the ear of the Lord Sabaoth. You have lived in luxury, and lived upon the earth in self-indulgence. You have fattened your hearts on a day of slaughter. (James 5:1–6)

Simply said, the earliest Christians were communists (as Acts tells us of the church in Jerusalem, and as Paul’s epistles occasionally reveal), not as an accident of history but as an imperative of the faith. In fact, in preparing my own recent translation of the New Testament, there were many times when I found it difficult not to render the word koinonia (and related terms) as something like communism. I was prevented from doing so not out of any doubt regarding the aptness of that word, but partly because I did not want accidentally to associate the practices of the early Christians with the centralized state “communisms” of the twentieth century, and partly because the word is not adequate to capture all the dimensions – moral, spiritual, material – of the Greek term as the Christians of the first century evidently employed it. There can simply be no question that absolutely central to the gospel they preached was the insistence that private wealth and even private property were alien to a life lived in the Body of Christ.

Well into the patristic age, the greatest theologians of the church were still conscious of this. And, of course, throughout Christian history the original provocation of the early church has persisted in isolated monastic communities and has occasionally erupted in local “purist” movements: Spiritual Franciscans, Russian Non-Possessors, the Catholic Worker Movement, the Bruderhof, and so on.

Small intentional communities committed to some form of Christian collectivism are all very well, of course. At present, they may be the only way in which any real communal practice of the koinonia of the early church is possible at all. But they can also be a tremendous distraction, especially if their isolation from and simultaneous dependency upon the larger political order is mistaken for a sufficient realization of the ideal Christian polity. Then whatever prophetic critique they might bring to bear upon their society is, in the minds of most believers, converted into a mere special vocation, both exemplary and precious – perhaps even a sanctifying priestly presence within the larger church – but still possible only for the very few, and certainly not a model of practical politics.

Therein lies the gravest danger, because the full koinonia of the Body of Christ is not an option to be set alongside other equally plausible alternatives. It is not a private ethos or an elective affinity. It is a call not to withdrawal, but to revolution. It truly enters history as a final judgment that has nevertheless already been passed; it is inseparable from the extra-ordinary claim that Jesus is Lord over all things, that in the form of life he bequeathed to his followers the light of the kingdom has truly broken in upon this world, not as something that emerges over the course of a long historical development, but as an invasion. The verdict has already been handed down. The final word has already been spoken. In Christ, the judgment has come. Christians are those, then, who are no longer at liberty to imagine or desire any social or political or economic order other than the koinonia of the early church, no other communal morality than the anarchy of Christian love.

you rich, how far will you push your frenzied greed? Are you alone to dwell on the earth?… Earth at its beginning was for all in common, it was meant for rich and poor alike; what right do you have to monopolize the soil? Nature knows nothing of the rich; all are poor when she brings them forth. Clothing and gold and silver, food and drink and covering – we are born without them all; naked she receives her children into the tomb, and no one can enclose one’s acres there.

Ambrose of Milan, “On Naboth”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Deborah Batt, Further Development, detail

Of course, the political import of this truth – at least, as regards action in the present – must still be sought. As I said at the beginning, I have no answer ready to hand. But, as I also said, we can at least define our terms. And we can certainly identify which political and social realities must be abhorrent to a Christian conscience: a cultural ethos that not only permits but encourages a life of ceaseless acquisition as a kind of moral good; a legal regime subservient to the corporatist imperative of maximum profits, no matter what the methods employed or consequences produced; a politics of cruelty, division, national identity, or any of the countless ways in which we contrive to demarcate the sphere of what is rightfully “ours” and not “theirs.”

Before all else, we must pursue a vision of the common good (by whatever charitable means we can) that presumes that the basis of law and justice is not the inviolable right to private property, but rather the more original truth taught by men such as Basil the Great, Gregory of Nyssa, Ambrose of Milan, and John Chrysostom: that the goods of creation belong equally to all, and that immense private wealth is theft – bread stolen from the hungry, clothing stolen from the naked, money stolen from the destitute.

But how to pursue a truly Christian politics at this hour – at least, assuming we hope actually to alter the shape of society – is an altogether more difficult question, and one that perhaps we shall be able to address only if we have truly first learned to disabuse ourselves of the material assumptions that capitalism has taught us to harbor over many generations.

Even so, in light of the judgment that entered human time in Christ, a Christian is allowed to long and hope ultimately for no other society than one that is truly communist and anarchist, in the very special way in which the early church was both at once. Even now, in the time of waiting, whoever does not truly imagine such a society and desire it to come into being has not the mind of Christ.

is not the person who strips another of clothing called a thief? And those who do not clothe the naked when they have the power to do so, should they not be called the same? The bread you are holding back is for the hungry, the clothes you keep put away are for the naked, the shoes that are rotting away with disuse are for those who have none, the silver you keep buried in the earth is for the needy.

Basil of Caesarea, “I Will Tear Down My Barns”

Sign up for the Plough Weekly email

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Wesley Paddock

The mistake that many people make is the assumption that Christianity is to determine the form of government we have. Communism in the early church only lasted for a short period of time. In Romans 13 Paul discusses our relationship to the government. Neither communism nor capitalism are "Christian" simple because we are not a political part. instead, we are a lifestyle committed to God.

A Euler

"Thou shalt not steal." If we are not to steal, there must be private property (i.e capitalism).

Lawrence Brazier

My leaning is towards David Bentley Hart's stance on wealth. However, perhaps we should not forget that the Plough texts are generally directed toward mature readers. There is tons of debate in every issue. Most theological points are talked over. Yet one wonders about the ur-cause and modern-day essence of our society. Most would agree that it is all "a bit far gone", to put it mildly, as far as social context is concerned. May I offer a thought or two, which I doubt many will gladly accept? It is is about the nuts and bolts of modern existence. When a child leaves the womb, generally screaming and who could blame it, that child immediately inherits five MUSTS. They are to breath, eat, drink, sleep and have protection from nature. Getting born into a family with a head start automatically gives the child the same. But the five MUSTS have to be maintained. It also means that the child MUST gain a foothold on life somewhere long the line. Did you notice that word "gain" in the previous sentence? This betokens the idea that (take a deep breath) a baby at birth is automatically a capitalist. With development to maturity a child could then handle his MUSTS and become a socialist, and, of course, a Christian- I do not write here about strong family generations of Christians, but about Mr and Mrs Average. Try telling an intelligent non-Christian that money is bad, that person is likely to suggest that money is ok, it is the people hanging around it who are often at fault. Oh well, only God is good.

Barry Lillie

Of all the imperfect means of distributing goods and services, capitalism is the least imperfect. All the others require coercion to work

Lawrence

Hmmmmn! One could contend that when a child leaves the womb that child "inherits" four "needs". The need to eat, drink, sleep and acquire protection against nature. The four needs can not be avoided - by either philosophy or any other system. No wonder most babies enter the world screaming. Parents with a little wealth can give a kid a kick-start into life. Poor parents are helpless. The four "needs" actually make every baby a Capitalist, automatically, and by definition in resepct of making their "way" in life, hopefully without malicious intent. Achieving maturity obviously means turning to the Lord after what has been called the age of reason. Christian parents are an obvious bonus.

Bob Taylor

Charity Fetters makes such comprehensive sense, I'm reluctant to throw in. But, I'm curious about Mr Hart. Does he live a communitarian life? And how does he expect his vision of the perfect system to come about short of worldwide Christian conversion, which the Bible makes sadly clear is not destined to happen?

Emmanuel Goldstein

Great article! Oddly enough, this reminds me of an essay I read some years ago, entitled, "Buddhist Economics," a chapter in the book, "Small is Beautiful" by E. F. Schumacher. If you google the title and author, it can be found and freely read in PDF. Schumacher points out that we do not need to base our economy on profits. There are alternative ways to organize work, including companies that are owned and run by their employees.

Larry Cheek

That opening is heresy. We are created for good works and given talents (to invest) as the parable explains. How else do es one make a living. greed yes, we are fallen. But rewards await the Christian whose works in the endwill pass the test.

suzi

Hi! You said that Commerce is, in its essence, satanic. That means capitalism is satanic. On the other hand as other expert told us communists were atheist (Antichrist). Who will be the perfect one that the community must follow? Thank You any way.

John DiGregorio

My guess is the early Christian communities succeeded (for a time) in being socialist (uncoerced, of course) because they shared the sacrament of the Eucharist. First comes ecclesial unity, then comes political/economic unity. I have no idea how this comes about but the point of Mr. Hart’s article was to define terms. I think he missed the critical starting point: Christians must first become visibly united in order to have a chance of making following Christ in sharing all good things attractive to hundreds of millions of people. Again, I don’t know how this can come about but individuals can take individual action. I suggest that Mr. Hart openly joins the Catholic Church.

Peter McCallum

"Even now, in the time of waiting, whoever does not truly imagine such a society and desire it to come into being has not the mind of Christ." D B Hart above. "My kingdom is not of this world." Jesus before Pilate. (John 18:36) In the spirit of communism I hope he contributed this article free of any capitalistic reward. The whole article all sounds so odd coming from one employed by possibly to two most capitalistic institutions in the world - Universities and the Roman Catholic Church. Both have immense wealth.

Adam Wesselinoff

Even though I broadly agree with DBH’s central arguments, I have always struggled with the unproblematic quoting of the Greek Fathers (whom, being Orthodox, I love) on poverty as an indictment of capitalism simpliciter. In part, I worry that doing so obscures the simple fact that we are burdened with both liberalism and the social contract, not just capitalism or even debt poverty. Surely the ‘state capitalist’ and the presupposition of individual right are just as pernicious opponents of the realisation of any evangelical norm in society. For instance: the state collaborates with capital not only to repress genuine attempts at political community but all mediating institutions that oppose the profit motive. Liberalism, especially in its final Rawlsian mode, provides the anthropological and metaphysical tools to do the same to the person: stripping away mediating notions of given identity and tradition (and even affect) that have real political importance. Just a thought after reading an enjoyable essay — thank you to the editors for having published it.

A Weak, Overplayed Argument

I'm not sure the author quite understands the basic economic premise of capitalism beyond just citing moral platitudes. The majority of value (90%) in a capitalist society goes to everyone. The remaining 10% (average profit margin of the S&P 500) goes to the capitalist. Example: Jeff Bezos is worth $100 billion, but he created $900 billion of value that the rest of us benefit from. Think: a lower income family can now order diapers more cheaply, in faster the time, than Peter could have delivered it to them on horseback in Jerusalem. *A smarter argument* would have been to compare the tradeoff's of the vice of greed (capitalism, but 90% goes to everyone else) vs. the vice of sloth (not doing your best work for society - much less value, in total, is created). Fortunately the author can act how he preaches and not invest his retirement account in the American economy, but rather, Italian municipal bonds, home of the Vatican, and witness the impact.

Douglas Rose

x "is a system in which as a general rule those whose work creates profits neither own the means of production nor enjoy the fruits of their labor” is X: a) serfdom b) slavery c) state socialism d) capitalism ?

Charity Fetters

I enjoyed this article and the needed accounting of capitalism's negative effect on society. There are some downfalls of capitalism that I hadn't really reckoned with before. The concepts are thought-provoking and challenging, especially in a day where capitalism seems to reign supreme. I do agree with a previous comment, however, that the term "communal" would be preferable to "communism". The word communism is so disdainful in light of its historical abuses and eventual molestation of society that it can no longer be used to describe any kind of idyllic hope for future economies. To his credit, the author acknowledges his own hesitancy to use the word communism, but doesn't quite provide a satisfying alternative and therefore stays too closely aligned with the problems of communism. For example, communism abhors private property and it seems that this is where the author is landing as well. Christ did not abhor private property, nor did He command EVERY follower of His to sell all that they had and give it to the poor. Mary and Martha still had their home, for instance. Very few followers (or would-be followers) were expected to sell all they had and give it away to the poor and literally follow Christ around. That is not even possible if you have children that you are to provide a home and a nurturing environment for, or if you have a sick spouse you need to take care of, or elderly parents to bring in under your roof. Simply stated there are other calls upon people's lives besides selling everything and giving it away. Rather, we are instructed to use our resources to benefit others...to share what we have (by Holy Spirit leading - not government enforcement) as if it belongs to the Lord and we are mere stewards of it - because it does and we are. We are to take the talent(s) given to us and expand upon them and use them for the glory of God and the well-being of others. The obvious conclusion is that we can't be stewards of resources if we have none. For some Jesus calls to sell it all, for some He calls to increase what they have and to steward it well in a manner that sustains self and others. To all He calls to "take up our cross, die to self, and follow Him". Any Christian-envisioned economy needs to acknowledge that God gives more to some than others and that personal ownership and responsibility means we are to care for others with what we have, while being open to the fact that some people within that communal system of stewardship and sharing will be called to literally divest themselves of all earthly goods in order to freely accomplish a mission Christ has for them without encumbrance. For these people , the rest of us should be keenly aware of their unique calling, which becomes our joyous burden to provide for their needs out of our own purses, property, and power. Looking forward to Christ's return and reign on the Earth does cause one to wonder what His idyllic world government will look like. Of course, He is coming back to reign as King and we will live within a perfect Monarchy, but until then we wish our world reflected our heart's desire to see everyone valued, nurtured, and cared for. I think ultimately this is what the author is wishing to convey. Great, thought-provoking article!

MICHAEL NACRELLI

Passages such as Eph. 4:28 and 1 Tim. 6:17-19 make no sense if total renunciation of private property is essential to Christian discipleship. Also, intentional Christian communities undoubtedly own assets. The real question is who controls them. It seems to me that a congregational form of church governance is the best way to prevent an undue concentration and possible abuse of power in such situations.

Grace Lyn Shockey

It is difficult to read of 'communism' without thinking of Marx, particularly if someone has lived in a Marxist country. And having lived in one, to put New Testament believers and Christ Himself in harmony with communism.

MICHAEL NACRELLI

A barrage of sweeping assertions with precious little biblical exegesis to support them.

John Jackman

This is a profound and important article. I wish that Hart had avoided the pitfalls and weighty baggage of the term "communism," however. A better term for the early church would be communalism. The Moravian communities of the 15th and 18th centuries captured this, as did many Mennonite and other communities. The golden calf of our nation is the idolatry of capitalism. The Founding Fathers were extremely suspicious of corporations, originally only allowing them to exist for seven years. They would not recognize the world we have today where corporations are treated as persons, and allowed to crush the rights of real persons in the name of maximum profit for the few. Hart articulates this well and accurately.

Daniel Krynicki

In 1943 Howard Benjamin Rand, LL.B, wrote in his “Digest of Divine Law”: “In these three important laws a perfect monetary system based upon the value of goods, services and the increase of our national wealth with the outlawing of usury and the institution of a system of taxation which is not confiscatory of property, the foundation will have been laid for an economic structure which in operation will be par excellent. Nothing that the socialists can conceive, nor the Communists desire, can be compared to the institution of the God-given system which will out-capital capitalism in that all men will become capitalists and ‘sit every man under his vine and under his fig tree; and none shall make them afraid; for the mouth of the Lord of hosts hath spoken it.’ In this statement is the assurance of food and drink, to replace the fear and want which is ever present with men under the present economy.”

Richard Clark

I just wanted to let Plough know how much I enjoyed the Summer 2019 issue, especially the article by David Bentley Hart "What Lies Beyond Capitalism?" I have known for many years that you cannot reconcile capitalism with Jesus' Sermon On the Mount. Bentley made this very clear in your latest issue.