Un-American: A Soldier’s Reckoning of Our Longest War

Un-American: A Soldier’s Reckoning of Our Longest War by Erik Edstrom

Erik Edstrom

(Bloomsbury)

Every reckoning of debt requires an accounting. Of course, not all debts are simply economic; some require us to use our moral imaginations to measure what we owe. What do we owe someone to whom we’ve lied? What do we owe the victim of a crime? Or, to take a slightly more complicated example which most Americans ignore, what are the true costs of America’s “forever war” in the Middle East?

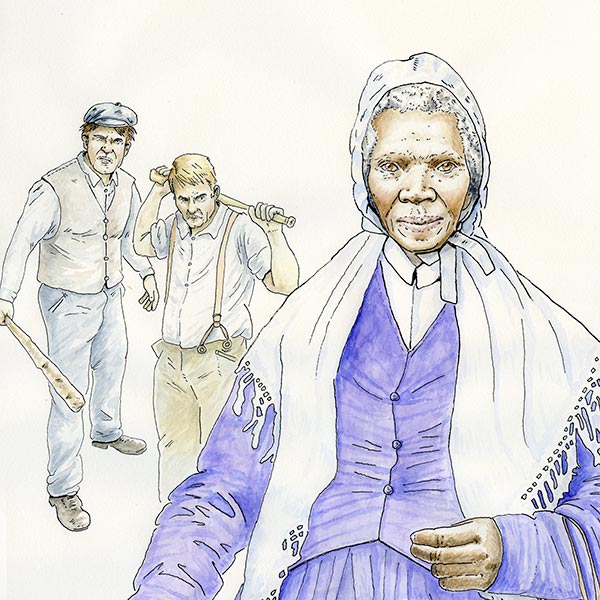

West Point alumnus and former Army officer Erik Edstrom wrestles with that question in this incisive memoir. He offers three ways one can begin to come to grips with the reality of US military presence in the Middle East: through an honest assessment of the war’s price tag in material terms and in opportunities lost by diverting resources to its mission, by imagining one’s own death in the war, and by imagining what it would be like to be subjected to a foreign occupying force here at home.

Don’t think that Un-American is a straightforward polemic. Edstrom pulls us into his life story, taking us along as he comes of age in blue-collar Massachusetts, succumbs to a pervasive jingoism as a high school student after 9/11, and is transformed into an unquestioning soldier at West Point. “One day . . . I crossed a line. I was now capable of hunting people. Not only that, I was looking forward to it.” Coming face to face with the actual evils of war – the charred bodies, the pointless missions, the skewed moral reasoning, and the pompous propaganda – gradually awakens Edstrom from the brainwashing of American militarism. “I was very lucky,” he writes, “I compromised my morals and had the formative years of my life amputated by serving in an unnecessary war,” yet survived to tell the tale.

So how do we reckon our war debt? The price in material terms and lost opportunities should be obvious. “America,” Edstrom writes, “has lost a chance to adequately deal with far larger threats, starting with the climate crises and followed by other important issues, including technological surveillance and data rights, AI and vocational retraining, infrastructure, education, health care, and wealth equality.” But even more powerfully, Edstrom asks us to put ourselves in the shoes of our so-called enemies, with a foreign force invading our own towns: “They . . . throw water bottles filled with urine at children. They disrespect your religion. They kill anyone in your community who actively fights back in self-defense.” They torture and raze and still have the audacity to tell you that they’re “only here to help, to free the oppressed.”

Un-American trenchantly questions the lack of moral vision in tabulating the cost of America’s longest war. It’s every bit as critical as anything by esteemed academics, while written in accessible language and hewing closer to the bone of lived experience. We owe it to ourselves to read it.

—Scott Beauchamp, author, Did You Kill Anyone?

Prison by Any Other Name: The Harmful Consequences of Popular Reforms

Prison by Any Other Name: The Harmful Consequences of Popular Reforms by Maya Schenwar and Victoria Law

Maya Schenwar and Victoria Law

(The New Press)

Journalists Schenwar and Law deliver a thorough deconstruction of a system they are convinced should not be reformed but abolished and replaced with an entirely reimagined approach to crime and justice. Though what they propose may seem extreme to some, even skeptics will benefit from reconsidering why our society keeps 2.3 million people locked up and many more under supervision and surveillance.

Law and Schenwar give a deep analysis of the harm inflicted through many so-called criminal justice reform efforts, which might reduce the number of people behind literal bars while in fact expanding the carceral net throughout our lives – into our homes, our communities, and our work until we find ourselves living in a prison nation.

The question driving Law and Schenwar’s analysis is “What is a prison?” They find that the state’s appetite for controlling citizens’ lives, enhanced by technological solutions and combined with a punitive approach to crime and poverty, already infects society well beyond the prison system. Specifically, the book explores probation, electronic monitoring, departments of child services, community policing, and the carceral nature of schools and drug treatment programs to reveal a landscape that under the guise of reform has grown the prison nation exponentially. The authors analyze the past several decades, during which a growing awareness of mass incarceration began to shift cultural awareness and the broader conversation around incarceration away from tough-on-crime to “smart-on-crime” rhetoric through the strange bedfellow alliances of the Koch brothers, the NAACP, and the Center for American Progress, to name just a few.

Commendably, the authors actually lay out a fairly detailed proposal for abolition and all it would encompass, offering concrete suggestions, not ephemeral dreams. This is a book to be taken seriously by everyone who cares about what transformative justice might look like.

—Jeannie Alexander, founder, No Exceptions Prison Collective

One Long River of Song: Notes on Wonder

One Long River of Song: Notes on Wonder by Brian Doyle

Brian Doyle

(Little, Brown)

If you’re not familiar with Oregon novelist and essayist Brian Doyle, think James Joyce, but with earnest faith. Joyce was haunted by his Catholicism, and it permeates his work. Doyle was also haunted by his faith, but in his writing that haunting blooms into joy, wonder, and some of the most agile, inspiring sentences in recent memory.

These collected essays are a posthumous gift to the world – Doyle died in 2017 of a brain tumor – and are as much performances of syntax as they are spiritual pilgrimages. Start at the perfectly placed first piece, “Joyas Voladoras,” a meditation on our mortal, weak hearts: “So much held in a heart in a lifetime.” In “Two Hearts,” he is angry at the God who caused one of his twin sons to be born with a heart condition – but knows “that this same God made my magic boys, shaped their apple faces and coyote eyes, put joy in the eager suck of their mouths.”

Doyle writes of flora and fauna, of childhood and basketball and pants and anesthesiologists and love – of all things we will miss, or already miss. His essays are apologias in both senses of the word – playful treatises that demonstrate the blessings of belief, and self-effacing jaunts through his own faults. Conversational and cathartic, Doyle has managed to give words to that epiphanic rush we feel when we catch a glimpse of the divine.

—Nick Ripatrazone, culture editor, Image Journal

Hunger: The Oldest Problem

Hunger: The Oldest Problem by Martín Caparrós

Martín Caparrós

Translated from the Spanish by Katherine Silver

(Melville House)

Right at this moment, eight hundred million people suffer from hunger. Twenty-five thousand die of hunger every day while one third of food produced worldwide goes to waste. In this meticulously researched book, Martín Caparrós asks why, and what we can do about it.

Caparrós travels to Niger, India, Bangladesh, the United States, Argentina, South Sudan, and Madagascar to talk with the poorest people on earth. They tell him about their daily lives: how they find food, what they eat, and why they struggle to get enough. He finds that those who suffer chronic malnutrition often do not realize it. Just-weaned children die in all these regions because they cannot make it on the nutrition-poor diet of their parents. Repeatedly parents tell Caparrós that they cannot understand why their children died; they fed them every day.

A hungry person, Caparrós notes, is someone you can exploit. Thus there are those who benefit from hunger, from speculators who steal land from traditional farmers to corporations such as Monsanto that entice farmers to go into debt to buy genetically modified seed rather than using seed they’ve saved themselves. Driven to desperation, farmers in India drink the very pesticide that buried them in debt. Meanwhile, powerful global institutions such as the IMF and World Bank regularly make decisions that redirect money away from efforts to feed the poor.

Caparrós tells us that the 375 pounds of corn needed to create enough ethanol to fill one tank of gas would feed a child in Zambia or Mexico or Bangladesh for an entire year. In another section he notes that in the United States, three dollars buys three hundred calories of fruit and vegetables or 4,500 calories of french fries, cookies, and soda, making the overweight and the malnourished victims of the same hunger industry.

Woven throughout the book is a detailed history of world response to hunger. Westerners are easily misled by statistics that are adjusted to make it look as if the problem were improving. “Numbers are the alibi for pathetic relativism,” Caparrós states – as long as we feel the situation is being addressed, we don’t develop the outrage needed to galvanize a response. We are, he writes, at a moment in history “when the previous paradigm has broken down, and another one has yet to appear.” He views that as reason for hope: with vision, leadership, and real struggles, the world’s oldest problem can be addressed.

—Suzanne Quinta, Fox Hill Bruderhof