Subtotal: $

Checkout

Should I Read Scary Fairy Tales to My Child?

My kids already know the world is not safe. Will dragons and goblins make it worse?

By Stephanie Ebert

December 6, 2024

“And then, the bunnies realized there was a dragon in the mountains, and – ”

“A good one,” my five-year-old interrupts the serial bedtime story I’ve been telling him about a rabbit family and their adventures. “The dragon is good. Not a scary dragon.” I concede that this is a friendly dragon, and the tale continues.

As I switch the lights off in my son’s bedroom and set our burglar alarm, I wonder about how easily I caved to his request. How young is too young to face danger in a story? Psychologists have long told us that fairy tales are important for child development. I tell myself that I believe this. I believe in the power of stories to help kids grow in bravery. Of course I do! And yet, now that I’m a parent, I see my own five-year-old self in their eyes, and I wonder if I’m willing to force my kids down these dark roads. If they don’t want scary stories, do they really need witches and goblins and dragons?

I was raised by evangelical missionary parents in 1990s South Africa, and my bedtime stories were downright terrifying. From missionary biographies, to George MacDonald’s fairy tales, to tales of people left behind by the rapture, my imagination was populated with far too many fearful things to make going to the bathroom in the middle of the night a safe venture.

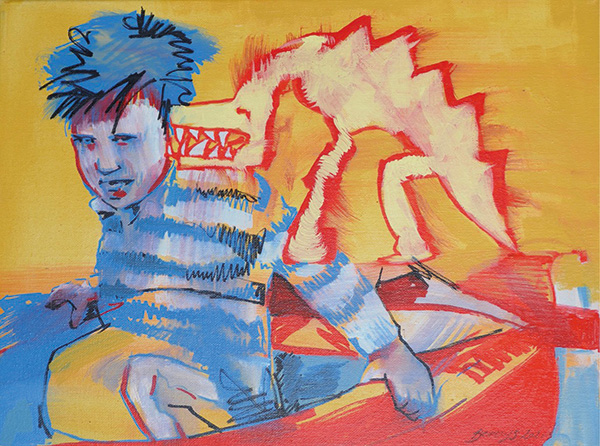

Amy Bernays, Our Afternoon, collaboration with child’s art, 2021. All artwork by Amy Bernays. Used by permission.

We read the Chronicles of Narnia, of course, but the White Witch was tame compared to the Enchanter in David and Karen Mains’s trilogy, Tales of the Kingdom. These stories, filled with brave rangers, heroic children, and a disguised king redeeming a city, did more to positively shape my vision of God’s kingdom than any other series. But the fire-obsessed Enchanter who enslaved the city alongside the Burners and Breakers – evil villains who captured children and branded them with red-hot pokers – also lived in my imagination. I would wake up from a nightmare, frozen in my bed, heart pounding in my throat. Forcing myself to run the gauntlet to the bathroom, I envisioned Burners in the shadows ready to snatch me. The Spirit Flyer series by John Bibee featured children with flying bicycles battling an evil toy-maker puppeteer who worked to enslave the town’s children under the motto, “Keep their fear hot and sticky.” Stories are one thing in the daytime. They’re another thing at night when everyone else is asleep, and the only sound is the ticking of your heart. Your fear is hot and sticky indeed.

These were our fairy tales. Beyond them, we also had nonfiction – the missionary biographies full of suffering for Jesus. We knew Jim Elliot was killed with a spear. We knew that William Carey’s wife went mad and died. We knew that being a Christian, especially the missionary kind, meant that God didn’t protect you from everything. Promises of the eternal presence of Christ in suffering or the “one day” of heaven were less real in my mind than John and Betty Stam’s beheading.

For this reason, perhaps stories of dragons and goblins are safer than stories of the nonfiction variety, but as a parent, I still hesitate. I’m not sure I want to fill my son’s head with images of Burners and Breakers lurking in the passage on the way to the bathroom. I’m not sure I want to populate his dreams with hooded men and glowing pokers, with enchanters and trolls. When my son says he’s scared, I believe him. These stories teach Christian virtues, embody spiritual truths, and recall the deeds of real-life Christian heroes. But I’m not sure I’m the one who wants to pour that hot and sticky fear down his throat, to trap him in his bed at night with witches and ghouls. I know what G. K. Chesterton would say. I’m not implanting the witches in my children’s minds; they’re already there: “Fairy tales do not give the child his first idea of bogey.… The baby has known the dragon intimately ever since he had an imagination.” I want to believe this – that I’m not the one giving my child nightmares of witches and dragons – but having been a highly sensitive child myself, I’m not sure it’s true.

Amy Bernays, The Wolf in His Ear, collaboration with child’s art, 2021.

Of course, I knew other stories as a child, much scarier than dragons. In the 1990s, South Africa was mercifully free of both apartheid and the civil war everyone thought would be coming. But there was an influx of weapons into the country, massive inequality, and a raging HIV/AIDS epidemic, and violent crime was peaking. These were not stories that my parents told us, but they were stories we couldn’t help but hear.

At school, children would out-shock each other with what they heard their parents telling around the weekend braais (barbecues). People were held at gunpoint at traffic lights and told to get out of their cars. My friend woke up in the night and saw a face peering through the crack in the curtains; when she screamed, her dad chased the intruder off their property. I carefully closed my curtains every night after that. Children swapped stories of carjackings, break-ins, and farm murders even as we traded items from our lunchboxes.

In some ways, these stories were more mythical than the imagined worlds found in the books I read. They were myths in the deepest sense – stories told around fires by adults as explanations and justifications for otherwise unexplainable reactions. They served as foundational texts for why these adults wanted to leave South Africa. They gave form to the buried fears that arose amid so much social change. There were grains of truth in them all, and yet not the whole truth. As an adult, in the daylight, I can grasp that reality is complicated. I can see that for some of my white friends’ parents, “I don’t feel safe” was just another way of saying, “I don’t trust black people.” But as a child, when I saw sensational headlines screaming from every newspaper bulletin tacked to the light poles on the drive to school, there was nothing complicated about it. If violent crime happened to people I actually knew, it could happen to me too.

My parents, realizing the sensationalism in the news, did a lot to shelter us. And even when things were legitimately dangerous, they sheltered us. When we were toddlers in the early nineties, before apartheid ended, my mom would sometimes have us make a house out of couch cushions in the hallway because of thunderstorms. We continued this game into elementary school, but it wasn’t until we were older that we learned the original “thunder” was actually gunfire. They didn’t talk about hijackings or crime at the table. They had enough friends living in marginalized areas to be aware of the actual dangers, and confidence that we were probably safe from the worst. They believed the crimes of a few could not take away the beauty of the freedom and reconciliation most people in our country then experienced. They understood that any violence occurring in a free country was minuscule compared to the years of violence at the hands of the apartheid government. And yet we still locked our doors, still shut our windows at traffic lights, still put our purses under the seats in our car, out of sight.

So, running the gauntlet from bedroom to bathroom did not just involve dodging terrifying men in bowler hats from the Spirit Flyer books, or the shadowy Burners and Breakers. There was that uncurtained window high up in the bathroom where anyone could look in. There were shuffles, creaky floorboards, the wooden ceiling groaning as it expanded and contracted in the heat. Was there someone else in the living room, waiting for me to get up? Should I pretend to be asleep?

The world is thick with evil, seen and unseen, real and imagined. It doesn’t matter where you live. And those of us who have been gifted with vivid imaginations perhaps need to be more discreet in what we allow in. Maybe other children could read about dragons, feel braver, and continue unscathed. For me though, the dragons were vividly real. And now that my child doesn’t want to hear scary fairy tales, I wonder – should I be the one to force him to?

Amy Bernays, Eurus the East, collaboration with child’s art, 2021.

My husband and I live in South Africa, and although things are much safer than when I was a child, last year we had a series of home break-ins. Multiple times, people entered our home and took things – from jackets to laptops to leftover food. We had fingerprinting dust smeared around our windows, police officers wandering the house again and again, sometimes at 2:00 a.m. I nearly grew used to the sound of the alarm on our electric fence, the alarm on our house, the flashes of lights in the middle of the night. I tried to think of my parents, sheltering us in the hallway as best as they could, striving to preserve our innocence with a game. But I had no idea how to turn this into a game. My son started hiding his piggy bank before he left for school in the morning.

Maybe I had been holding off on the stories of the White Witch and her wolves, dragons and goblins because it felt like the last thing I could control. I can’t stop the onslaught of the violent world invading his dreams; I can’t keep out a burglar, or sensational headlines, but I can make sure there are no goblins in his hallway. I can make all our dragons good dragons.

But maybe I have it backwards.

Maybe Chesterton is right. Maybe in a world full of thieves and guns, death and addiction, I need not wait to give him the gift of fear in the pages of a book. Maybe the stories are scary not because the Enchanter is scary, but because the fear, hot and sticky, that my son already lives with every day can be found there too.

And maybe if my son can recognize the fear, he can also recognize the courage. Because the fairy tales never end with the dark. The magic bicycles can fly, after all. Their headlamps blaze through the darkness, destroying ash-eating snakes and evil puppeteers. Chesterton goes on to say that “what fairy tales give the child is his first clear idea of the possible defeat of bogey.… What the fairy tale provides for him is a Saint George to kill the dragon.”

Maybe I had forgotten what it was that got me out of bed to the bathroom every night, even with fear clawing my chest. Because although the hallway was populated with evil creatures, somehow, night after night, I managed to get through. It was the gifts of light from those same scary stories that helped me do it. Gifts of Bible verses, chanted like an incantation to drown out my imagined fears: “The Lord is my light and my salvation, of whom shall I be afraid?” The knowledge that Princess Amanda in the Tales of the Kingdom series defeated dragons, just as the king defeated the Enchanter. The book’s motto, “Sighters are not afraid,” sung over and over when my Bible verses ran out.

Maybe I too easily forget that these stories, filled with danger and darkness, can also help build memories of goodness and strength. Like Digory and Polly’s memory of Aslan in The Magician’s Nephew, maybe my children can experience enough goodness in a story that they can say “that as long as they both lived, if ever they were sad or afraid or angry, the thought of all that golden goodness, and the feeling that it was still there, quite close, just around some corner or just behind some door, would come back and make them sure, deep down inside, that all was well.” Maybe the weapons of light, like Peter’s sword and Susan’s arrows, and the knowledge that the full might of Aslan is always just around the corner, are strong enough gifts to carry my child through the long hallway from the bathroom back to bed.

After our series of break-ins, our family went on a camping trip. Sitting at the fire that night I mustered my courage and told my son, “We’re going to read one of my favorite stories. And it’s scary. But it’s good. I promise. You will get scared, but in the end, it will be OK.”

It’s scary, but God is good. In the end, it will be OK. Isn’t that the message of our Christian hope, in a world full of evils, both real and imagined? I opened the book and began, “Once there were four children whose names were Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy.…”

Elizabeth Gedert

Thank you so much for this article. I also have a five-year-old son who doesn't want to hear or watch anything "scary." I too grew up with Narnia and have wrestled with whether to deliberately give him something I know is scary. Your simple language that it is scary but that it is good in the end is very helpful.