Subtotal: $

Checkout-

The Best of Times, the Worst of Times

-

Return to Vienna

-

You Can’t Go Home Again

-

Two Poems

-

Why Inheritance Matters

-

Not Just Nuclear

-

Dependence

-

The Praying Feminist

-

Letters from Death Row

-

The Beautiful Institution

-

Putting Marriage Second

-

Singles in the Pew

-

New Prince, New Pompe

-

Manly Virtues

-

God in a Cave

-

Editors’ Picks: Issue 26

-

Little Women, Rebel Angels

-

Sojourner Truth

-

Covering the Cover: What Are Families For?

-

Another View: Sunday Supper

-

Proteus Unbound

-

The First Society

-

The Corporate Parent

-

Family Matters

-

Letters from Readers

-

Family and Friends: Issue 26

The Case for One More Child

Why Large Families Will Save Humanity

By Ross Douthat

November 18, 2020

Available languages: Français

Start with the car seats. They hulk in the back seats of any normal sedan, squeezing the middle seat from both directions, built like a captain’s chair on Star Trek if James T. Kirk was really worried about taking neck damage from a Romulan barrage. The scenes of large-family life from early in the automobile era, with three or four kids jammed happily into the back seat of a jalopy, are now both unimaginable and illegal. Just about every edition of Cheaper by the Dozen, published in 1948, uses an image of the Gilbreth kids packed into the family automobile, overflowing like flowers from a vase. Today, the car seats required to hold them would take up more space than the car itself.

In his 2013 book, What to Expect When No One's Expecting, Jonathan V. Last described “car seat economics” – the expense and burden of car seats for ever-older kids, the penalties imposed on parents who flout the requirements – as an example of the countless “tiny evolutions” that make large families rarer. Obviously car seats aren’t as big a deal as the cost of college or childcare, or the cultural expectations around high-intensive parenting. But it’s still a miniature case study, Last suggested, in how our society’s rules and regulations conspire against an extra kid.

Our society’s future would be radically different if people simply had as many kids as they desired.

Seven years later, two economists set out to prove him right. In a paper entitled “Car Seats as Contraception,” they argued that car-seat requirements delay and deter the arrival of third children, especially, because normal backseats won’t hold three car seats, so you basically can’t have a third young kid in America unless you upgrade to a minivan. The requirements save lives – fifty-seven child fatalities were prevented in 2017, the authors estimate. But they prevent far more children from coming into existence in the first place: there were eight thousand fewer births because of car-seat requirements in 2017, according to their calculations, and 145,000 fewer births since 1980.

You don’t have to quite believe the specificity of these numbers to see that an important truth is being revealed. Our society is not exactly more hostile to children than societies in the past: indeed, once an American child is born, her girlhood will be safer from all manner of perils than the childhoods of the 1980s, let alone the farm-and-factory past. But this protectiveness coexists with a tacit hostility toward merely potential children – children who might exist, children who are imagined when people are asked about their ideal family size, but who, for all kinds of reasons, are never conceived or never born.

We lack a moral framework for talking about this problem. It would make an immense difference to the American future if more Americans were to simply have the 2.5 kids they say they want, rather than the 1.7 births we’re averaging. But talking about a declining birthrate, its consequences for social programs or economic growth or social harmony, tends to seem antiseptic, a numbers game. It skims over the deeper questions: What moral claim does a potential child have on our society? What does it mean to fail someone who doesn’t yet exist?

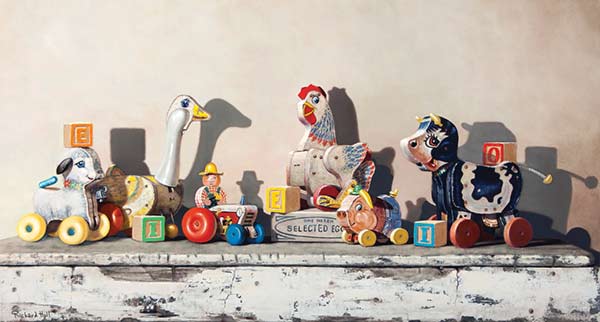

Richard Hall, EIEIO All artwork by Richard Hall. Used with permission.

I think about this with our daughter Rosemary, our fourth child, six months old as I write. We weren’t sure if we could have her, or if we should. I had been sick with a debilitating illness that maybe – not officially, but definitely anecdotally – can be passed along to children. My wife carried the scars of several caesarean sections. We had moved three times in five years, losing money as we went. Much more than with any of her siblings, having Rosemary was a leap of faith.

She was conceived in the summer of 2019. In the winter of 2020, I brought Covid-19 home to my family from a book tour, and our other children and my seven-months-pregnant wife got sick. Rosemary was born amid the first wave of the pandemic; her birthday matches the exact late-April peak of deaths for our home state of Connecticut.

After we brought her back from the hospital, healthy and cheerful, I thought about what would have happened if news from 2020 had fallen back through a wormhole into 2019. Guess what? Before you conceive another child, you should know that there will be a pandemic next year, the economy will shut down, there will be riots and a crime wave, and you’ll all get sick with the virus, deep into your wife’s pregnancy. Would Rosemary have been conceived in the shadow of that foreknowledge? Would we have made the leap?

Because of course now that she is here she has inestimable value. How could the challenges of 2020, however dire they might have sounded as prophecy, possibly justify her non-existence? How could we not have pressed ahead, if the endpoint was her friendly cheeks, her babyish giggles, her oh-so-human eyes?

The idea that not-enough-Rosemarys might be a problem for the world has taken a long time to take hold. The consensus during my youth held that falling birthrates were always a sign of progress, that Third World overpopulation might doom the world to famine, and that anyone who cared too much about Western fertility was probably a crank.

I took this gospel for granted as a child: I remember quizzing my dad about how the earth could possibly survive the combination of overpopulation and pollution. But I also came young to the realization that the problem might lie elsewhere. Sometime in Bill Clinton’s presidency, I was assigned a high school science bulletin-board project on population trends. In the library I checked out all the books on overpopulation – which meant basically the collected works of Paul Ehrlich, the alarmist author of The Population Bomb. When I compared their 1970s-era projections to what was actually happening, my teenage self could see two things plainly: first, none of the disasters Ehrlich envisioned had come to pass, and second, for the rich world the population trend was an arrow pointing down and down and down.

The birthrate is entangled with any social or economic challenge that you care to name.

I was hardly the first person to notice this: P. D. James’s dystopian prophecy of mass infertility, The Children of Men, came out five years before my bulletin-board revelation. But the fear of under population belonged to the realm of weirdos and conservatives (but I repeat myself) well into my adulthood. When Hollywood got around to adapting James’s novel in 2006, the film focused more on terrorist disturbances and cruelty to immigrants than the horror of a childless world. When countries in East Asia and then Eastern Europe began to search for policies to bolster birthrates, they were regarded as illiberal curiosities.

It was only when the US birthrate, long an above-average outlier among rich nations, began to descend anew following the Great Recession that the topic began to spark stirrings of real interest. But even now there’s no agreement that the birthrate deserves as much attention as healthcare or taxes or abortion or police brutality, let alone that it might be one of the most pressing issues of our time.

Yes, Republicans can be induced to include a little family-friendly tax policy in a larger tax reform, and Democrats support family subsidies when they’re cast as measures to fight poverty. But to argue that the American future depends on pushing our birthrate back above replacement level, as Matthew Yglesias did in his recent book One Billion Americans, remains an eccentric argument to many people: an interesting idea, maybe, but not a particularly urgent one, and certainly not the sort of issue that would make the cut of questions for a presidential debate.

Which is a bit crazy, when you stop to think about it. Whether a society is reproducing itself isn’t an eccentric question; it’s a fundamental one. The birthrate isn’t just an indicator of some nebulous national greatness; it’s entangled with any social or economic challenge that you care to name.

As social scientists have lately begun “discovering,” a low-birthrate society will enjoy lower economic growth; it will become less entrepreneurial, more resistant to innovation, with sclerosis in public and private institutions. It will even become more unequal, as great fortunes are divided between ever smaller sets of heirs.

Richard Hall, Lost My Marbles

These are just the immediately measurable effects of a dwindling population. They don’t include the other likely effects: the attenuation of social ties in a world with ever fewer siblings, uncles, cousins; the brittleness of a society where intergenerational bonds can be severed by a single feud or death; the unhappiness of young people in a society slouching toward gerontocracy; the growing isolation of the old.

Families can be over-sentimentalized, imprisoning, exhausting. But they supply goods that few alternative arrangements can hope to match. No public program could have replaced the network of relatives that helped my grandfather live independently until his death – even if, yes, his five children, my mother and aunts and uncles, had often feuded with him and each other over the years. No classroom is likely to supply the education in living intimately with other human beings that my children gain from growing up together – even if the virtue of forbearance is not always perfectly manifest in their interactions.

Yea, thou shalt see thy children’s children, and peace upon Israel, runs the Psalmist’s blessing. A society of plunging birthrates withdraws the first blessing, and compromises the second day by day.

But to identify these problems is to run into a question: Whose responsibility, exactly, is it to fix them? One reason that the healthcare system and the tax code come up at presidential debates is that both involve official choices about how to regulate and spend. But the government cannot conjure babies (yet), and fertility decisions belong to an intimate sphere that we rightly insulate from the reach of state coercion. And modern societies feel uncertain about whether they can even ask people to have kids, since that implies a moral obligation to have children.

Such an obligation was assumed by most peoples in human history, but most peoples were not us: freed from patriarchal demands, liberated from economic systems in which an extra pair of hands is an automatic asset, proud of the opportunities available to women, too secular to accept “be fruitful and multiply” admonitions, and conscious that there are eight billions of us and counting on an earth whose environment is, put mildly, under strain.

Still, even for a secular society it isn’t hard to generate a moral-obligation-to-procreate case. You can just play the utilitarian game: Society should seek the greatest good for the greatest number; there is no good so essential as existence, so society should be organized to maximize, within reason, the number of people that exist.

I said within reason because that’s how even the most child-friendly parents tend to think. You have to go pretty deep into religious traditionalism to find people who don’t do anything to space their children, and put their childbearing exclusively in the hands of God. The rest of us, even the people who embody what a Washington Post journalist once called “smug fecundity,” tend to balance the number of kids they have against some other perceived good: not just health or the demands of some humanitarian vocation, but education, real estate, professional ambition. And, of course, the desire to someday get a little sleep.

But maybe this “reasonability” concession gives too much away. A famous rejoinder to the utilitarian case for more kids is that it leads to what the philosopher Derek Parfit termed the “Repugnant Conclusion” – namely, that so long as we consider existence itself a utilitarian trump card, we have to conclude that for “any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better even though its members have lives that are barely worth living.”

The supposed repugnance of this conclusion need not be conceded. The religious believer who regards suffering as freighted with potential moral purpose will have a very different reaction to a phrase like “barely worth living” than the typical secular utilitarian. The world of one hundred billion people who suffer tribulations might produce more saints; the world of ten billion people enjoying unparalleled hedonic pleasures might be under divine judgment.

Yet in framing the choice to have more kids as something that we should favor only within reason, aren’t we tacitly embracing some version of Parfit’s thesis – in the sense that for ourselves, we assume that there exists some family size whose possible tribulations exceed the good of an extra human being’s existence? Aren’t even we, the relatively fertile, minimizing our obligation to children yet unborn?

Perhaps medieval categories can help us. Perhaps we can say that the unique sacrifices required of parents – and let’s be clear that they’re required of women more than men – make the absolute case for children a counsel of perfection, a marital equivalent to the chastity and poverty and obedience demanded of members of consecrated life. The family that is open to new life unstintingly, eschewing not just contraception but any kid-spacing caution, is living a supererogatory life, going beyond the basic requirements of the moral law, in a way that we should admire without feeling condemned if we cannot do the same.

Just how many kids would count as supererogatory under this moral theory is another question. Kid-spacing caution was invented long before the 1960s, but clearly people in the past wouldn’t have regarded four or five kids as some sort of heroic, saintly, half-mad effort.

On the other hand, we shouldn’t overestimate the gulf between past and present either. People in many premodern societies married later than historical clichés suggest, and infant mortality rates meant that how many kids you bore was tragically different from how many kids you raised. Raising five children to adulthood would have been very normal in, say, seventeenth-century New England, but raising a Quiverfull-style dozen would have been exceptional even then.

The goal should be to help more families have the kids they already say they want.

Since my wife and I obviously did some spacing of our children, I’m aware that the decision to have only a “reasonable” number can be driven by all kinds of non-saintly, self-justifying considerations. But the idea of reasonability definitely influences how I think about persuading other people, my more secular neighbors especially, that more kids would be better. I don’t expect America to suddenly become filled with ten-kid families driving hulking vans. Rather, in a rich society with a plunging birthrate, the plausible goal should be to help more families have the kids they already say they want, meaning not six or eight or ten, but just one more – the kid who requires a new car seat and maybe a new SUV, the kid they feel like they might be able to afford, the kid you can feel pretty sure they won’t regret.

So what keeps us from that one-extra-kid world? One answer is that too many people fear that the repugnant scenario is here already – that overpopulation and climate change will between them usher in a future of unparalleled misery.

“Meet Allie, One of the Growing Number of People Not Having Kids because of Climate Change,” runs a recent NPR headline. Miley Cyrus recently declared her intention to refrain from procreating until somebody fixed the climate crisis: “I refuse to hand that down to my child.”

I’m not sure I believe her, though. I know there are some people who are sincerely child-free because they fear the ecological impact of overpopulation. This strikes me as a deeply mistaken approach to the climate crisis – above all, because any long-term solution will require exactly the kind of human ingenuity that a stagnant gerontocracy will tend to smother. But I can concede that it has some coherence, some altruistic pull.

Richard Hall, The Great Escape

Those I doubt are the people claiming that they’re refraining from having children for the kid’s sake, in a reversal of the argument for a moral obligation to have kids. Humankind has existed this long because people have borne children under radically difficult circumstances, amid famine, war, and misery on a scale we can’t imagine. Nothing in the potential life awaiting Miley Cyrus’s hypothetical daughter promises hardship remotely comparable to those ancestral burdens. And even if you think climate change will be truly apocalyptic, it’s no more threatening than the prospect of nuclear annihilation, which did nothing to prevent the last great Western baby boom.

No: In most cases, invoking climate anxieties seems more like an excuse, a gesture to ideological fashion, than a compelling explanation of low fertility. There has to be a deeper cause.

So let’s name three. First, romantic failure – not just in breakdowns like divorce, but in the alienation of the sexes from one another, the decline of the preliminary steps that lead to children, including not just marriage but sexual intercourse itself. Some combination of wider forces, the postindustrial economy and the sexual revolution and the identity-deforming aspects of the internet, are pushing the sexes ever more apart.

Second, prosperity, in two ways. One, because a rich society offers more everyday pleasures that are hard to cast aside in the way that parenthood requires. (Nothing gave me more sympathy for the childless voluptuaries of a decadent Europe than the first six months of caring for our firstborn.) Two, because prosperity creates new competitive hierarchies, new standards for the “good life,” that status-conscious people respond to by delaying parenthood and having fewer kids.

Finally, secularization – because even if it’s possible to come up with a utilitarian case for having kids, the older admonitions of Genesis appear to have the more powerful effect. The mass exceptions to low birthrates are almost always found among the devout, and the big fertility drop-offs in the United States correlate clearly with dips in religious identification.

The first of these three causes comes latest in history: the alienation of the sexes is mostly a post-1970s phenomenon, and previously any trend had run the other way. (More American women were married in the 1950s than in the 1880s.) Wealth and secularization, on the other hand, come in together centuries back, and entangle in all kinds of complicated ways.

In How the West Really Lost God, her provocative theory of secularization, Mary Eberstadt argues that the waning of the family led to declining religiosity rather than the other way around. Thus, for instance, the secularism of the Millennial generation might reflect their experience growing up as children of divorce, with weaker kinship networks leading to weaker ties to churches and other forms of communal life.

But I suspect it’s wiser to see the whole process as a set of feedback loops: the rich society creates incentives to set aside faith’s admonitions, which orients its culture more toward immediate material pleasures, which makes its inhabitants less likely to have children, which weakens the communal transmission belt for religious traditions, which pushes the society further along the materialist-individualist path.…and at a certain point you end up, well, here, with unparalleled prosperity joined to seemingly irresistible demographic decline.

So how might it be resisted? One answer is the kind of self-consciously reasonable vision I’ve already invoked – the push to just get back to replacement-level fertility, the push for one-extra-kid for families on the fence. The hope would be that the car-seat economists are right, and that simply by making family more affordable – reducing the cost of childcare or of a parent staying home, reducing the cost of education, reducing the cost of home buying, and so on – you can change both the immediate incentives and the cultural expectations around having kids.

Even if you think climate change will be apocalyptic, it’s no more threatening than the prospect of nuclear annihilation, which did nothing to prevent the last great Western baby boom.

The more it seems affordable to have a third or fourth child, in this hopeful theory, the more relaxed the whole culture might become – with less shaming of the fecund poor, less eyebrow-raising at large families in the upper middle class, and a lot more leniency for parents towing their broods on cross-country flights.

The more you deliberately organize institutions around supporting families, the more children would seem like a complement to education and opportunity rather than a threat. And the more you take family formation seriously as a policy goal, the more you transcend certain fruitless culture wars, and move toward a world where more mothers work part-time or stay home while their kids are young and more fathers play the paternal role that made possible not just Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s career, but Amy Coney Barrett’s as well.

I have some hope in this vision, in part because I move back and forth between secular and Catholic worlds – from contexts where we’re an oversize family to contexts where we’re below-average wimps. And so far in the secular world I don’t see all that much of the judging and hostility that some parents of large families report. (Though maybe the judging only kicks in once you have five or six.) Instead, I see a certain amount of friendly admiration, joined in people older than us to a mild I wish we’d had three instead of two regret.

Richard Hall, Duck Crossing

Meanwhile, from the strange worlds of mommy bloggers and Instagram influencers all the way up to the Duggars of TLC, our pop culture manifests at least as much fascination with large families as it does with overpopulation fears. Maybe this fascination is itself a symptom of ill-health, a weird voyeurism about something that should come naturally. But at the very least it’s an homage that sterility plays to fecundity, and a signifier that there are lots of people who might have more kids if their situation felt slightly different, if economic pressures changed and cultural expectations altered with them.

Again, that’s what I’d like to believe can happen. But there are still times, many of them featuring the overwhelming exhaustion you feel at the end of a professional-parental day, I think that no, to get lots more people to sign up for this kind of lifestyle, you would need something more than a “parenting more than two kids: it’s more feasible than you think!” pitch. You would need our society to become dramatically unlike itself, ordered to sacrifice rather than consumption, and to eternity rather than what remains of the American Dream. You would need not change on the margins, but transformation – probably religious transformation – at the heart.

Certainly you can see the possible limits of policy tweaks and cultural nudges in the experience of other countries. The rich society that fully acknowledges an obligation to the unconceived may not exist, but many societies, European and Asian, do much more to support parents than the United States. And their results are not overwhelming: at the margins, policy can encourage births, but usually that means going from 1.4 kids per woman to 1.55, or 1.7 to 1.8 – gains that are fragile and easily swamped, both by specific events (like the Great Recession or the coronavirus) and by larger trends like the continued retreat from marriage and intimacy.

For the average sinner, life with children establishes at least some of the preconditions for growing in holiness.

So perhaps a greater cultural change in what we want is needed, even for a goal as modest as a fertility rate that matches our professed desires. And this change might not actually start with (even if it would necessarily include) a renewed sense of obligation to generations yet unborn. Instead, it might start with what we the living want and seek out for ourselves.

The libertarian economist Bryan Caplan once wrote a book called Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids, which falls mostly into the nudging sales-pitch category: it’s a list of reasons why having a big family is more compatible with normal late-modern ideas of fulfillment than many people think.

The deepest reason to have more kids, though, is self-centered in a radically different way. It’s that if you don’t feel cut out for spiritual heroism, if you aren’t chaste or poor or particularly obedient, if you aren’t ready to be Mother Teresa – well, then having a bunch of kids is the form of life most likely to force you toward kenosis, self-emptying, the experience of what it means to live entirely for someone other than yourself.

This can circle back to egotism, admittedly, for people who make idols of their children or practice a ruthless selfishness toward everyone outside the charmed circle of their household. Jesus called us to leave behind fathers and brothers for a reason: it’s still holier to be Francis of Assisi than a dad.

For the average sinner, though, for me and maybe for you, life with children establishes at least some of the preconditions for growing in holiness, even if there’s always the risk of being redirected into tribal narcissism. If I didn’t have kids there’s a 5 percent chance that I’d be doing something more radical in pursuit of sainthood; there’s a 95 percent chance that I’d just be a more persistent sinner, a more selfish person, because no squalling infant or tearful nine-year-old is there to force me to live for her and not myself.

But the idea of parenthood as enforced kenosis is very different from the idea that having more kids is swell and good and all-American. The large family as a spiritual discipline, children as a life hack that might crack the door of heaven – if that’s the worldview required to make our society capable of reproducing itself again, then we’re waiting not for child tax credits, better work-life balance, or more lenient car-seat laws, but for a radical conversion of our hardened modern hearts.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Mary Boctor

I think often parents heavily consider the material obligations they have to existing children when considering more children. It's a flawed calculus, though, because it takes into account only material realities; it fails to consider the intangible (and tangible) ways that more siblings might benefit the existing children. So maybe when talking about obligations, we should focus not on obligations to not yet existing children (this seems to pose ontological difficulties...) and focus on the fullness (ie not just material)of obligation to existing children.

Rae

A few points: Falling birthrate does NOT increase inequality as you posit. Having fewer children is our fight AGAINST inequality. How can a divorced public school teacher get her kid into Harvard for a PhD? I managed it by only having one. She is the least privileged in her cohort. Of your two articles on the subject that I've read so far, the only anti-natalist you're railing against published in 1968! Whereas natalist articles are published regularly. I still don't see any convincing arguments for more procreation. Why, exactly, do you think the pros outweigh the cons? And the main problem with your whole approach is that men don't have a say. They don't have the child, so they don't get to weigh in. If you really want children so badly, then squeeze them out of your own ...

Joshua C. Frank

I’m happy that you’ve written an article like this. The low birth rate alone is proof that liberalism, along with everything else about the modern world, is simply unsustainable. Natural selection will favor cultures that have large families. Can anything justify refusing to bring into existence a child whom the couple and they alone can give life? Few people regret having one more child, but many regret contracepting or otherwise “planning” one away, just as many women who have abortions regret doing so.

Sahara Lefevre

Interesting read!! This writing touches upon the serious implication of having a Micro family.. Just the other day I was in conversation with a newly married couple, and I was infact encouraging them to have more than just two kids. Thank you Plough Team for this insightful writing.

Lorien Chang

in a world where birth control exists, and without coercion by men or society at large, it is women who ultimately determine fertility; the author mentions, but then glosses over, the fact that women shoulder more of the burden of raising children than men do. It was more possible for a single income to provide for a family back when large families were the norm, and income that could be made from home (farming, weaving, piece work, etc) more readily before that. Modern western women are largely working part- to full- time, just like men, and then coming home to shoulder the lion's share of home- and child-care as well. At some point, more children means even less sleep, and less sleep means less sanity and less health. Is it any wonder that many women choose not to grind themselves to dust on this wheel? The 'expense' of children is not just measured in dollars.

Susan

What about the moral obligation to homeschool. Women flooding the job marketplace depressed wages for all sole breadwinners, making a perpetual cycle of two career slavery. If only Rosie stayed home to school her children and care for granny, we would not have the technocratic house arrest police state foretold by humanae vitae.

Danielle R. Postlewait

Excellent article. You stick your neck out on a topic that clearly (from the harsh criticism received) is not popular. You make points about larger families and children in general that are not obvious to us; we are not attracted to growth in godliness or even character development as much as we are in consumption. We say we are very concerned about climate change, yet personal lives are spent devouring as much as we can and promoting that image. Thank you for being willing to be torn up by the opposition received.

James

I find it interesting how many words you used to write an argument that could have been made in a few paragraphs. A lot of “over-writing” in this essay. It’s unfortunate because there are some interesting points nestled in the excess verbiage.

Hank Fanning

Douthat is correct that suffering (which is what we will all experience more of in a more populous world) can improve one's moral character. But *causing* people to suffer in the hope that it will improve their character (which is what you are doing when you choose to have large numbers of children) is not Godly. Also, Douthat is far too optimistic in estimating how many people this planet can support at even a poor standard of living. With the coming collapse of the chemical-based agriculture system and massive water shortages, our choice is not between 10 and 100 billion, but between 3 billion and 2 or less.

Ken Kline Smeltzer

Though interesting, Douthat’s argument is fatally flawed in its most basic proposition, namely that “there is no good so essential as existence, so society should be organized to maximize, within reason, the number of people that exist.” If he had said “creatures” instead of “people” I might agree. Though life might be better for living humans with fewer people crowding and exploiting the earth, the better reason for limiting human populations is to leave room for the rest of creation. We are wiping out species and animal populations right and left as we expand our heavy footprint on the earth. We are not God or the only creatures of divine value. Douthat’s totally anthropocentric argument is inherently imperialist and for religious folks turns into a crusader mentality of self-deification. It is akin to an ethnic and theological stance of superiority, gained through ever-expanding numbers and technological prowess, not faith in God, reverence for creation, or simple righteousness. The kingdom of God isn’t just for people. When will we realize that we aren’t the be-all and end-all of creation?

Andy B.

It feels a bit sentimental to chalk this up to modern hard-heartedness. The article mentions this in passing, but children have really flipped from an economic boon to an economic drain in the last hundred years or so, which almost perfectly coincides with our declining birth rate. When children were free labor and potentially your only defense against poverty in your old age, you tended to have lots of them. Now that they aren't, you don't. These circumstances still tend to roughly correlate with birth rate now, depending on where you live. Reducing the economic burden of having a family likely only moves the needle a little because there is no wealthy country in the world where children are predictably a good deal financially. Some places just manage to make it a little less hard.

Justin

It is certainly an issue of strain on the middle class family. Forget the car seats. One parent used to stay home and take care of all the things needed to secure a healthy large family or small family for that matter. The middle and poverty classes just keep getting squeezed for all the work and have to keep adjusting to more and more time gone from the family while kids are left to parent each other. As soon as the uppers are ready to sacrifice their wealth for the food of all gods people, that is when the world will look differently.

Roger Lloyd

Thank you for Ross Douthat’s interesting article, “The case for one more child”. I particularly appreciate his thoughts on children helping us to discover “...what it means to live entirely for someone other than yourself”. However, I struggle with some of the other points he makes: • The “moral-obligation-to-procreate case”. Surely this needs to be seen not just from the perspective of a rich and powerful country, but from that of a world where so many live in poverty, and power structures favour the “haves” to the increasing detriment of the “have-nots”. • I would maintain that the world is struggling to support the current human population. The article observes that any long term solution to the climate crisis will need plenty of human ingenuity. Certainly, but should not the focus be on empowering the disempowered, educating and equipping those who, through no fault of their own, do not have access to education, or, so often, any sort of family life because of poverty, war etc? By thinking in terms of “my country” it is difficult not to end up with the arguments about “social programmes or economic growth or social harmony” which lead to an overriding concern for the prosperity and power of “my country” in a world where so many need help and support. Do we think nationally or globally? And what should be our attitude to those who are the victims of national and international power struggles? • The statement that climate change is “no more threatening than the prospect of nuclear annihilation...” The nuclear threat in the days of the last Western baby boom was not acted on – for which we should all be very grateful. But climate change is impacting the lives of many people across the world now. This process is set to increase, but it is already destroying lives and livelihoods, and radically changing vast areas of the world.

Ya chaka omnist

This would make a lot more sense to people if the emphasis was on RAISING more of society's children, those that ALREADY exist and need a loving home... not birthing more and more and doing nothing about the surplus pool of humans that also deserve to be love and raised and inherit the earth...

Lawrence Brazier

Well, quite obviously the "desire" part of having as many children as "desired" could be a a wonderful testimony to one's trust in God. But go figure. According to Buddha desire was what led to unhappiness. Nevertheless, every Christian has his or her understanding according to God's benediction. I know it may sound crazy, but I yearn for a life with Christ with no philosophy, no desired outcome, no special meaning other than simply being a person who at least does not add to the chaos we call every day life. In other words, I need grace. Love to you all.

Steve Bell

U have got to be having a laugh kids need feeding clothes a good house a good education it costs money I have been blessed with a fantastic job but we were only ever having 2.

Debbie Laffey

People are not having more children because they cannot afford them. That is a personal decision! Who wants to bring a child into the world of a parent cannot afford medical care or education for that child? I call that a smart decision when a couple thinks through any major decisions together.

Prof. Joseph

I think this is an interesting article which does a nice job of quantifying the intangibles. You really cannot put statistics on the satisfaction a new human relationship brings not their creative potential. I would have loved to hear the author address "non-traditional methods" of growing a family. Would not adoption, fostering, and sponsoring portend the same benefits mentioned whilst also addressing the social issues of neglect and overpopulation? Furthermore, it would help those of us who may be convinced by the article but beyond childbearing years to imagine solutions that benefit society and are aligned with personal, religious, and environmental convictions. But perhaps that is for another article.

David Rensberger

A remarkably self-centered answer to the alleged self-centeredness of small families. With only a slight, rather sneering nod to people concerned about the climate, does Douthat look forward ever more billions of people somehow beating the earth into submission? But the earth is the Lord's, and the Lord evidently did not create it submissive. A few large families, genuinely loved and well provided for, is great. Large families as the norm, in a no-longer-agrarian society where aging into the 80s is usual, is plainly unsustainable. When the overall human population is both of the right size and of the spiritual commitment to live in harmony with the rest of creation rather than exploiting it (see Psalm 104), then large families will be both delightful and sensible again. Especially so if we dads pull our weight at home, and share in that deepest human joy, caring for children.

Barb Foster

I was very disappointed with the article The Case For One More Child. I suggest that people research the environmental impact of having one more child. The facts about the impact of various acts on climate change are readily available.

Fr William Bauer

We adopted an infant (3 days old then) in 2012. I will be 91 when she is 18. It's a good world.

at

My wife and I (married well over 40 years) have 7 children and 17 grandchildren. Yes, we are Jewish and we believe G-d takes care of us. That's our business. I would not surrender one of them for anything under the sun. They are all beautiful and amazing, and every one of them is a brand new world.

Jerome Barry

Ross, with the Biden administration vastly increasing refugees and vastly decreasing border enforcement, you should find a way of counting all immigration as a substitute for live births per woman. That's the way that Democrats and Corporations want to get a workforce, and that's the way it will be done.

Richard

Ross, As a member of the Roman Church, of course you think this. This High Church, Laudian Episcopalian rejects many doctrines of the Church of Rome and questions whether you even understand what it means to be sinners in a fallen world. We have been given stewardship of creation, and we are failing miserably.

James

I am amazed at all the comments by people who know what will happen in the future. The author is correct, the rewards of having children, and the concomitant costs, cannot truly be measured. We are more than economic units, much more. And by prompting us to think through what that means, personally as well as corporately, the author has done us a service and deserves thanks.

Kate Riley

Thank you for this thoughtful discussion. It helps the birthrate that we cannot know the precise contours of our future, that there'd be a pandemic, a war, or other tragedies. But we do know, subconsciously, that tragedy will always be with us. And yet we have a child anyway. Each one is an expression of hope.

taek kenn

My husband and I had 4 children because we loved having children around us. You have to first love people before you can love children. If you do not love people you will not like having children around you. It is not always easy, but nothing that you love and that is worthwhile comes easy.

Linda Conroy

I would be grateful if, at some time, some from Plough could offer me information about why you have choose to ignore the global scientific evidence that overpopulation is a KEY factor in our present climate crisis. Maybe the first question I need to ask is, do the publishers of Plough acknowledge that there is a global climate crisis? I have sometimes shared articles from Plough with the Stillpoint community so I am asking for myself and for our community. Thank you.

Rukiya Braiman

Economic hardship , high level of education, improper upbringing of children due to pressure.

Lathechuck

As an electrical engineer with about 40 years experience, I can assure you that we will be fortunate if we can allow the world population to decline naturally (as it is) fast enough to accommodate declining energy resources before the remaining population is left rioting over the remaining food. A finite world does not support infinite growth. Meeting the demands of a growing population is much easier for a philosopher to propose when he's not the one who has to meet it.

Debbie Laffey

People can not afford having a large family. Some people do not want to have children.

Winnie Hohlt

I believe any woman who truly wants a child should be able to have one. I believe just as firmly that any woman who does not want a child deserves to do whatever she can to protect herself from pregnancy or to end an unfortunate pregnancy and that the definitions thereof should be left to the woman/ women alone. Do I make I e myself clear? Thank you.

Betty Purchase

Thanks for bringing this issue up. We always felt that our family made a difference for children who were the " left behind". We reared 2 children who were 'street children' from Tampa, Florida and have continued to be our children. There were times when we had 7 children, when mothers were suicidal. In those days there was no Social Service working at this level. We believe children must be seen in new ways.

Evan Leister

The article that I resonated most with was "The Case for One More Child" by Ross Douthat. I loved two things about it. First, the concept of children as a kind of everyman's sanctification is very relatable. Second, I think this is applicable to everyone, not just people who are in faith and community traditions where there are large families already. My wife and I jointly probably would have settled on 0-1 kids as our ideal, but we now have two and I love them both dearly. My main struggle with family is how to care for the aging previous generation when their ideal was a paradox of sending their children to far off regions of the USA for economic advancement when also expecting us to move back to be present for their later ages in life. I don't think that any of the articles in this issue addressed this other than to prescribe vague cultural ideals of accepting lower economic possibilities for the benefits of being closer to family.

Mary Ann Conrad

This article is thought provoking, and I agree with his conclusion that we need a radical conversion of our hardened modern hearts, that siblings create the perfect first circle of socialization, and that parenting is one of the holiest callings of life. With my husband I have parented birth, adoptive, and foster children. I am not sure that Douthat adequately addressed concerns of overpopulation, and I was surprised that he never raised the option of foster care. Overworked caseworkers in almost any state will happily fill your backseat. Opportunities for kenosis and the surprising joys of parenting abound. There will be considerably less temptation toward tribal narcissism and when you are lucky, an expanded definition of extended family.

Robert H Appleby

The article The Case for One More Child by Ross Douthat brought back memories for me. We were married in 1986, said that we would have 12 children. Well after the first one (9 months after our marriage), we decided that 6 would be enough. All our children are born in March, as we were married in June. The second son came 2 years after the first, and the third son came after 2 years of the second one. We were about to say stop, but decided to try for a girl, and right on schedule, 2 years after the third son, we had our girl. Well, we tried to not have any more children as my wife was being run ragged. Contrary to her beliefs, she decided the best way out of our dilemma was a tubal ligation. Thus, our case for having more than 4 was decided. Now after 13 grandchildren (12 still living), and 3 great grandchildren, we are very content in our family size. The whole issue of Plough is a pleasure to read.

Sarah Sanderson

I wanted to like Ross Douthat's "The Case for One More Child." The data was fascinating, and the call for more social supports to young families was spot-on. But his pivot at the end from "families can't have more children because it's too expensive" to "families need to have more children to make them less selfish" left me cold. To make such a claim, particularly without a further discussion of the unique ways that additional children impact mothers differently than fathers--a fact that Douthat admits briefly but does not unpack--feels condescending and patriarchal. As a young woman pregnant with my fourth child, I wrestled mightily with the Quiverfull theology that Douthat seems confident nobody outside fundamentalism will take too seriously. I had not been raised a fundamentalist, but I was deeply concerned about pleasing God, and deeply worried that God might want absolute control over my womb. After that fourth child was born-- my fourth in seven years without a single break between pregnancy, breastfeeding, pregnancy, and more breastfeeding-- I landed in the psychiatric hospital with postpartum psychosis. When a psychiatrist told me I needed to be done having children, I took it as a word from the Lord. Recently a young mother I know, with a history of mental health struggles of her own, told me that after months of agonizing, she and her husband had decided that their first child would be their last. I couldn't be prouder.

Matthew Graybosch

Parenting is an full-time and unpaid job. Until that changes, there's no upside to having children in the "rich world", and no philosophical or religious argument can stand against this cold economic fact: we don't get paid enough for this.

JN

Two more thoughts as a mom of three (who initially didn't want any kids and now wish I had more!). 1. I think technology can plan so much for us that young people get used to never being out of control: always knowing the weather forecast, how to get somewhere, what you'll do when you get there, realistic career paths, etc. Getting pregnant and having a kid is almost entirely out of your control. 2. Long-term birth control like IUDs are great in many ways (I had one implanted after my third kid was born), but takes more effort to get removed and so if you're wishy-washy on trying to get pregnant, you just won't do the additional effort of going to the doctor to get it out, etc. I've seen that in myself (though I'm 41, so odds for a fourth are low anyway!) and friends. I also think what many women don't anticipate is that how many kids you want changes over time. At 32 you may think you just want one, at most two, and then you find yourself six years later yearning for a third and at the tail end of your fertility. Great article, though.

Mike

I'm surprised to see someone as intelligent as Douthat falling into the fallacy of supposing that we can have moral obligations to entities that don't exist and might never. A moral obligation to a non-existent entity is the same as an obligation to nobody, which is a logical impossibility. You might just as well say that we have a moral obligation to create Frankenstein's monster, so that he exists, or to create sentient robots. And looking at it through the lens of Utilitarianism does nothing to solve this fatal error: If an entity doesn't exist, it can't benefit, so it can't be included in the Utilitarian calculus. You might argue that we have a moral obligation to God, or to posterity, or to our ancestors, or to the Earth, to continue the species/our civilization, or to create saints, or to subdue the Earth/galaxy. But there can't be a moral obligation to hypothetical beings. People fall into this error because, in the process of imagining additional children, the mind personifies them, and comes to feel like they already exist on some level--as though they're up in Heaven sitting around waiting to be procreated, and will be let down if it doesn't happen. As for the more general question, my feeling is that the main thing driving the decline in fertility is the luxury and comfort of adult life in rich countries, and that the share of childless adults is probably not going to decrease in the foreseeable future. It may be easier to get people who like having kids to have 3/4/5 rather than 1/2/3 than to get people who like childlessness to have 1/2. If that's true, then having kids could become something of a specialization, with large numbers of households with zero kids, and larger numbers with 3/4/5/etc.

Mark Gilmour

I enjoyed this. Lapsed Catholic myself so some points went past me, but this is a powerful argument even from a secular perspective. I'll address something a few commented a have raised: The only solution to climate change is technology. Reducing the population or our ecological footprint is just not practical in a way where the cure isn't worse than the disease. The solution is clean energy, geoengineering, and carbon capture. The only way out is through: we need to become a rich and advanced enough society to be able to be proper stewards of the earth. And a growing population makes this easier. You only need to invent a technology once to spread it across the world, and the more people we have in rich countries the more scientists and engineers we can support. The marginal extra child of the sort of person who cares deeply about climate change is a blow against global warming, not for it.

Meiling Lee

Unfortunately Douthat does not take the hypothesis that "young people" don't want children due to the climate crisis seriously. In contrast to nuclear annihilation, nuclear annihilation did not happen and is unlikely to happen in the eyes of many. Meanwhile, severe negative effects from climate change are *inevitable*, as we will in fact see severe weather events, lower food production, modest population migration and severe ecological upset. Likewise, while economy is important in justifying an additional child, why not consider the economy to society as a whole with increased immigration? It has been shown that immigrants do improve economy, and it would enrich not just current US citizens but immigrants who would otherwise be in less productive economies (though I refrain from commenting on access to healthcare). Let not our xenophobia blind us from immediate, mutually beneficial solutions.

Rory

Just came across this article. All I can say is I agree. Also, I have five kids... From 22 to 9. I'd probably have more if I could. Luckily I have my 1st Grandchild (8 months old) to fill the gap. Have babies. Besides, in 1000 years, no one will care about anything we did in our personal lives. The only measure of you will be how many descendants you have.

Jean-François Goyette

Very well written article. I enjoyed reading it.

MICHAEL NACRELLI

The nuclear war analogy is flawed because population growth doesn't inherently increase the risk, as is the case with climate change, deforestation, species loss, water depletion, and other environmental crises. Douthat is right about the perils of demographic decline in developed countries, but he doesn't adequately address the ecological aspects of the issue.

Megan

What about the Christian's obligation to adopt? How does that play into big families, population, and contraception? (Adoptive parents are not all infertile, as widely believed! :)). Why can't those who choose not to have children due to climate change adopt? These kids are already here! Great points about kids decreasing selfish tendencies in parents and how this is desirable. I try to tell my nulliparous friends this and they think I am crazy!

paradoctor

You speak of a Baby Boom raised in defiance of Cold War terror; but those Boomers are themselves low in fertility. I myself simply didn’t have the heart to court, wed, and father a child under Cold War conditions. Why go to all that trouble just to raise another sacrifice to nuclear Moloch? Then the Berlin Wall fell, and I told myself that maybe we’ll live after all. Love, marriage and a child followed. But only one, because by then she was at the upper age limit of fertility. For me, and I suspect many others, superpower thermonuclear terrorism is contraceptive.

Hope Hulet

I am the fourth child in a family of eleven. My parents are expecting number 24 and 25 grandchildren. When we have a family reunion it’s explosive!! Thanksgiving my cousins came with their growing families. We set our table for 60 people. I can not describe the power and strength that a large Christian home has. When we were young my mom would receive heckling and shame in the store. Something has changed in society because I shop with my 6 children all the time and people are always giving me admiration and encouragement. I thought that when I had number 5 I would receive grief but was shocked that I never have. Well, once. A crazy lady outside Wal Mart. But overall even strangers seem to enjoy seeing a large family.

James

Good read. I disagree with one point. Dads can be just as holy as St Francis. Some men are called to spiritual fatherhood, others to the raising children. There isn't more holiness in one calling than the other. Great points all around. I'm left with this idea: have a great family, it will inspire others to do what they already want.

Ali Phelps

I was shocked by this article. ( I'm writing from the UK, so appreciate that perspectives may be different.) The climate emergency is not only real and now, but WE are causing it. I want to make my role as a steward of the Creator's beautiful earth and Jesus' command to Love one another my guidelines to making choices. Each baby in the developed world uses 586 times more resources than a baby in the less developed world . This increases tragic hardship to our least resilient brothers and sisters and seems plain unfair. However hard I recycle my cans or stop flying, it's almost nothing compared to reducing the number of consuming children. (Brandalyn Bickner, a Catholic one time Peace Corps volunteer from Chicago has a great personal story) Of course, reducing my carbon footprint is not the only important current issue, and having babies is a very personal choice, guided by the Holy Spirit in people of faith. I don't want to become judgmental and lose conversations with those who see things differently. My personal story: We have 2 (now adult) kids, and I had wanted more. I liked the lifestyle. It gave me fulfilling purpose and I'd hoped to become a better mother having made plenty of mistakes on the first two. My husband was reluctant, he understood more (and cared more) about the global impact than I did. But the Lord spoke to me through Matthew 19:12 'Some are born eunuchs, some are made eunuchs and some are eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven' What if the Lord wanted something other than natural motherhood of me, 'for the kingdom?' At least I had 2 kids. So I treasured them a bit more, practised not being jealous around all the new babies in my community and discovered accidentally that we had room to respond to emergencies. We fostered kids , welcomed homeless individuals, the separated and asylum seekers and had so much laughter on the way. I am still using every ounce of mothering within me, just not with blood relatives. And I had space in my life when the church asked me to work on the team. I'm glad the Lord knew better than I did about baby numbers.

Christina

“And even if you think climate change will be truly apocalyptic, it’s no more threatening than the prospect of nuclear annihilation, which did nothing to prevent the last great Western baby boom.” How can you NOT think climate change will be apocalyptic? If you lived where I do and saw the massive fires that are increasing yearly, or if you lived in places struck by the recent hurricanes and were homeless and hungry, maybe you’d think differently. The threat of nuclear annihilation is still here, by the way, but has not stopped people from having kids—it’s a threat, but one we all hope and pray will stay under wraps. It didn’t stop me from having a child. The threat of a virus that might come along and kill us all is similarly unlikely to cause people to skip childbearing. Wars have never stopped us. Climate change, on the other hand, is already here and is already disastrous. It’s not a theory, and it’s happening far faster than scientists had predicted. There will be more fires, more hurricanes, more flooding year by year. The nuclear threat is real but is also avoidable. We can get our act together and get rid of the weapons, with enough will power and concern for all of these children. Climate change, however, is unlikely to be solved at this point; it is already causing terrible suffering and death, mostly in the poorer countries, so it’s easy to pretend, sitting in some of the wealthier nations and cities, that it’s not going to be truly apocalyptic.

Cait

Wow... thank you. I have never heard a real argument for having more kids, let alone one so complete and well thought out. I have two kids, 6 and 7 years old. I was so overwhelmed when number 2 came so quickly after number 1, and I kinda burnt out. We also have moved several times, and amidst chaos of life we have always had a reason why it is not a good idea to have another right now, and every year that goes by makes it harder to want to get out the diaper bag, the stroller, the bassinet, all the blankets, the cloth diapers, get a new carseat, the training potty, and do it all over again. I have always wanted more kids, but have been thinking for several years that maybe there is a better time than right now, and we will just wait until things calm down a bit, and feel more stable. I do not know if things will ever calm down, or feel stable again, and right here in the midst of my childbearing years I am suffering the fear I may never have another, because of this ever growing list of reasons why now is not the right time. I don't think the right time I hope for will ever come. It may require a significant amount of sacrifice on my part, and may invoke a certain level of anxiety at times, and will surely cost me hours upon hours of sleep I could have had, but I want to look into those little eyes, and see a first smile again. I want to teach someone to walk again. Why do I not already have that child? Feeling afraid. Afraid of the world, and where things are going. Afraid of the finances. Afraid of needing to buy a new car, make the SUV jump. Afraid of the weight I might put on. Afraid of the current medical system, and feeling like in order to honor myself, I may need to find the strength and resources to traverse a lot of this unknown journey on my own. After reading your article, I feel inclined to be brave. Bravery is not the absence of fear, it is just prioritizing something more than avoiding what you fear. If that baby was here, it would be easy to prioritize anything he or she needed, but because they are not here yet, and I can't see the sparkle in their eyes, it feels hard to fit that priority in. I am encouraged by this article, and feeling ready to get brave, and take the leap to have another baby, because there will never be a better time than now.

Barbara Penna

I love this well balanced and thoughtful article. Left out, though, is the fact that there is no logical reason to have kids. They are inconvenient and a financial drain. It is an emotional decision, with untold emotional rewards. How can the joy of an infant's laugh, a 6 year old's hug, a daughter's engagement, be measured? The author's best argument for having more children (even just one more) is for the socialization that occurs between siblings. Friendships come and go, but family is forever. I raised 3. Acquired 2 more through marriage. Still I wish I'd had more.

Alan S Drake

The ideal should be a slowly declining population with no smooth age cohorts. Say -0.3%/year. @ 240 years to cut the population in half. The savings in fewer children far exceed care for the frail elderly. So overall fewer resources for those at dependent ages. Infrastructure need be only replaced with minimal expansion. Per capita GDP & Quality of Life will be significantly improved. Managed & moderate population decline is better than endless expansion of population - the philosophy of a cancer cell.

Marissa Burt

Good words. I agree that large families are counter-our-current-culture, a necessary good to be desired (if not always granted) in Christian marriage, and a very real gift to ourselves and the broader community. Children are, in fact, a blessing - whether we sense the reality of that when stretched thin by many of them or in our worries over climate change, etc. I don’t expect a secular/pagan mindset to fully embrace or affirm this though I am saddened when I encounter “child-free” talking points in the church. We need better catechism. I remember 20 years ago as a mainstream Protestant there was zero discussion of marital sexuality and children - family planning, birth control, etc. was incontrovertible conventional wisdom. I was shocked to learn a year or two later the church has historically had quite a lot to say about this... I do think there’s a very small subset of secular culture that’s come to love and embrace the messy joy of large families, but I think even these movements are born out of God’s design and struggle without his broader life-giving ways, for instance, it’s difficult to maintain a large family without a commitment to marriage. Your final points made me think of what I recently read in Ronald Rolheiser’s book Domestic Monastery: “Carlo Carretto, one of the leading spiritual writers of the past half-century, lived for more than a dozen years as a hermit in the Sahara desert. Alone, with only the Blessed Sacrament for company, milking a goat for his food, and translating the Bible into the local Bedouin language, he prayed for long hours by himself. Returning to Italy one day to visit his mother, he came to a startling realization: His mother, who for more than 30 years of her life had been so busy raising a family that she scarcely ever had a private minute for herself, was more contemplative than he was … What this taught was not that there was anything wrong with what he had been doing in living as a hermit. The lesson was rather that there was something wonderfully right about what his mother had been doing all these years as she lived the interrupted life amidst the noise and incessant demands of small children. He had been in a monastery, but so had she. What is a monastery? A monastery is not so much a place set apart for monks and nuns as it is a place set apart (period). It is also a place to learn the value of powerlessness and a place to learn that time is not ours, but God’s.”

Plougher

Wow. This was very well written all the way through. The car seat economics stuff is too real.

Diane Peske

OMG Ross- this is the best thought piece on this subject I’ve ever read!!! My husband and I had 5 children which seemed enormous in our upper middle class Southern CA world. I always pined for more even as my body had to stop. We currently have 14 grandchildren... and the place I draw the greatest hope for their future is every Sunday Mass when I see young parents struggling with squiggly toddlers and older families with a brood from pre-school through college. Thank you for penning this

Joe at Plough

What do you think? Can society evolve to accommodate and support larger families? Or is conversion the answer as Douthat suggests?