Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Poem: “Blackberry Hush in Memory Lane”

-

Poem: “A Lindisfarne Cross”

-

Poem “Fingered Forgiveness”

-

God’s Grandeur: A Poetry Comic

-

Birding Can Change You

-

Disability in The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store

-

In Praise of Excess

-

A Church in Ukraine Spreads Hope in Wartime

-

Toward a Gift Economy

-

Readers Respond

-

Loving the University

-

Locals Know Best

-

A Word of Appreciation

-

Gerhard Lohfink: Champion of Community

-

When a Bruderhof Is Born

-

Peter Waldo, the First Protestant?

-

Humans Are Magnificent

-

Who Needs a Car?

-

Covering the Cover: The Good of Tech

-

Jacques Ellul, Prophet of the Tech Age

-

It’s Getting Harder to Die

-

In Defense of Human Doctors

-

The Artificial Pancreas

-

From Scrolls to Scrolling in Synagogue

-

Computers Can’t Do Math

-

The Tech of Prison Parenting

-

Will There Be an AI Apocalypse?

-

Taming Tech in Community

-

Tech Cities of the Bible

-

Give Me a Place

-

Send Us Your Surplus

-

Masters of Our Tools

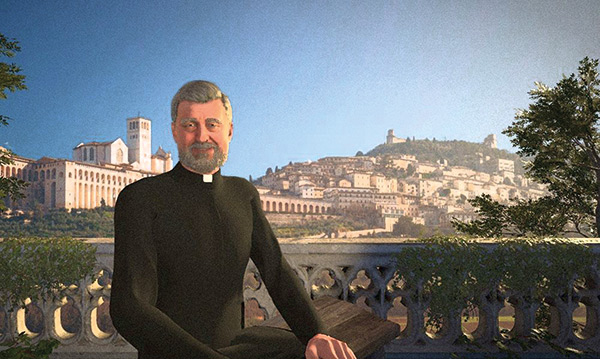

ChatGPT Goes to Church

Should large language models write sermons and prayers?

By Arlie Coles

June 6, 2024

In a 1999 episode of the church comedy The Vicar of Dibley, the vestry meets to discuss how to lift Vicar Geraldine’s spirits after her breakup with the womanizer Simon. Alice, the daft though creative verger, has a solution. “You know the series Walking with Dinosaurs?” she ventures. “Well, they recreated the dinosaurs digitally, just using a computer. I thought maybe we could do the same with Uncle Simon.” Mr. Horton, the churchwarden, repeats dryly: “Recreate him digitally?” “That’s right,” says Alice, “then send the digital Simon round to the vicarage.” A beat passes, and Mr. Horton clarifies: “So we get a holographic, two-dimensional human to marry the vicar?” Alice nods, and Mr. Horton looks around for help responding to her technically impossible and morally absurd suggestion. “Does anyone spot the defect in this plan?” he asks. No one does, and the vestry votes through Alice’s motion.

Working in artificial intelligence research since ChatGPT launched often makes me feel like hapless Mr. Horton. We researchers are surrounded by onlookers and their suggestions, some having neither desirable goals nor methods in the realms of reality. For example, some suggest outsourcing middle and high school teaching to a chatbot. Its inaccuracies “can be easily improved,” claims an academic dean at the Rochester Institute of Technology. “You just need to train the ChatGPT.” Or, as the tech entrepreneur Greg Isenberg suggested last year, we could task a language model (LM) with writing and marketing the next Great American Novel; all we have to do is code up a program and “start selling.” Each time a public figure urges this kind of unfettered and unrealistic application of LM technology to tasks far too human to morally bear automation, I hear the harried churchwarden’s voice: Recreate him digitally? Does anyone spot the defect in this plan?

Artwork by William / AdobeStock. Used by permission.

Yet in many cases the vestry has voted the dubious motions through. Modern LMs have launched a thousand bullish startups and a thousand uneasy think pieces. Many doubt the wisdom of hastily applying LM technology to areas classically sitting at the core of human creative activity – writing, teaching, interpreting – especially as the general public discovers what machine learning researchers already know: LMs are not omniscient and can, in fact, generate garbage. Moreover, some worry, if LMs are by nature garbage-generating machines, does using them relegate us to mediocrity? Will we let our human creativity atrophy? And, seriously, what real need – not simply the desire for the last scrap of profit at the expense of human pursuits – do LMs give an answer to?

Why have LMs suddenly and dramatically seized our attention? Where should the church say, “Thus far and no further”? Few are truly equipped to assess the deadlock, but as a speech and language AI researcher and a churchwoman, I will attempt the task.

The public reaction to ChatGPT’s launch in November 2022 exceeded industry expectations. OpenAI, its creator company, had called the launch a “low-key research preview,” and many in the wider research community were poised to see it as another incremental though impressive improvement in the long line of LM research. LMs are a workhorse class of statistical model that, as the public now perhaps knows, have one job: to return the next most probable item in a sequence. An LM will predict “mat” given “the cat sat on the” because, roughly, we give it a count of how many times “mat” appeared in that context in some other text corpus, and if that count is high enough, we set it to output that item given the context. LMs have powered common AI applications for decades, including the predictive text suggestions in your next tweet and your last email, so why the explosion of public interest now?

Today’s chatbots offer the glittering peril of instant gratification. Products like ChatGPT are strictly speaking not just LMs, but LMs plus extra statistical steering to facilitate a question-and-answer format, plus a slick web interface enabling any person on earth to type in a query and receive a fast response. This chatbot framing is technically incidental. But it is rhetorically and psychologically powerful, a rapid feedback loop so easy to enter that it has implicitly taught the public that the purpose of an LM is to generate content on demand.

And to generate answers. Our tendency to conflate quick responses with correct responses when talking to humans also transfers onto the chatbot, which we can’t help but personify. A fast and confident-sounding chatbot may mimic the authoritative voice of a reference work, and it may draw from and contribute to our habits of laziness when seeking out truth and our impatience when engaging each other.

“Father Justin,” an AI chatbot designed to answer questions regarding the Catholic faith, started giving false guidance and even offering one user absolution as a “real” priest, raising questions over the limits of AI in the church setting. Screenshot/Catholic Answers.

Researchers know – but seldom effectively communicate – that indispensable LM applications sit just one level deeper than the “type query, get content” chatbot paradigm. That’s because LMs are only accidentally content machines; they are substantially a dense statistical representation of relationships between words. Eliciting those relationships for a downstream task can be valuable. Borrowing heavily from John Firth’s distributional semantics maxim, “You shall know a word by the company it keeps,” LMs compress and store information about the whole distribution of words in all the text they see. Their insides and outputs are a mathematical study of language as it is actually used, and researchers can and do leverage that information not to drown us with spam, but to promote our good.

One can use a printing press to print libel. But that is not what it is for. What, then, ought LMs to be for?

They are, already, part of innumerable systems that humanize, not alienate – speech recognizers whose generated transcripts are important accessibility tools for deaf people; translators that allow immigrants in tight spots to communicate; record systems that alleviate medical professionals’ documentation burdens and allow them to spend more time at the bedside. Their value can even return to the fields that provided their data. LMs are helping to decipher dead languages, restore lost ancient inscriptions, and predict protein structures. They are tools that, in the hands of intrepid researchers and, yes, entrepreneurs, are well suited to facilitate our exploration of the world and our rapprochement with one another. But none of these mentioned applications use LMs as cheap content machines; they are harder to understand (and get less press) than the instant feedback an impressive or appalling chatbot provides. Our attention spans are short; our demand for content is high. The high-strung discourse around LMs is, in a sense, what we deserve.

And what of the church? Some clerics have voiced concerns about AI writ large, ranging from the pastoral – how should a priest help a parishioner following an automation layoff? – to the theological – can an LM be possessed by a demon? (And, if so, is it the same demon that always pops up in the printer when it’s time to produce bulletins during Holy Week?) Others are more optimistic about the possible elimination of drudgery. This divide mirrors the one in the public’s discussion of AI, with one faction wishing to seize the low-hanging fruit, while the other asserts that from the beginning in the Garden, knowledge of when to appropriately seize fruit has hardly been humanity’s strong point. The fact is, if the church implements suggestions for how to use LMs that are as shallow and dehumanizing as the suggestions that have lately come out of secular society, we will live to regret it.

The first truly interesting suggestion for LM use in the church is to leverage them for organization of language-based materials. Many helpful assistive technologies flow from this: subtitling, transcription, translation of services, searching past sermons or resource documents, and so on. Insofar as these ideas increase access to the life of the church, they can be healthily pursued. But two dangers lurk around this corner.

One temptation is to jump from using LMs to organize text to using LMs to interpret text – including the ultimate text, the Bible, which ought to be wrestled with and interpreted in the human community knit together by the power of the Holy Ghost. Some enthusiasts have advised pastors to save time by using LMs to generate devotionals and Bible discussion questions, but one cannot excise the humanity from these and still obey the call to personal and communal wrestling that Holy Scripture demands.

Technically, the returns will diminish because of the nature of LMs: they will return shallow text probabilistically biased toward any religious text in their training corpus. Spiritually, while LMs may marshal text effectively, they can neither “read, mark, learn,” nor “inwardly digest” it. Meditating on divine words is what human beings do in their inner being. This technically cannot and morally should not be automated. Mary could not have outsourced her pondering of the angel’s words to an LM, not only because an LM’s next-item-prediction objective is not pondering, but also because it would have denied those words’ ability to form her. A pastor might provide his congregation with a Bible study written by another pastor or a church father – but its author is still a person in relationship with the universal church, an inward digester, who, though having died, is alive in Christ and truly helps form the congregation. Rejecting this in favor of artificially generated text is an affront to the reality of the communion of saints.

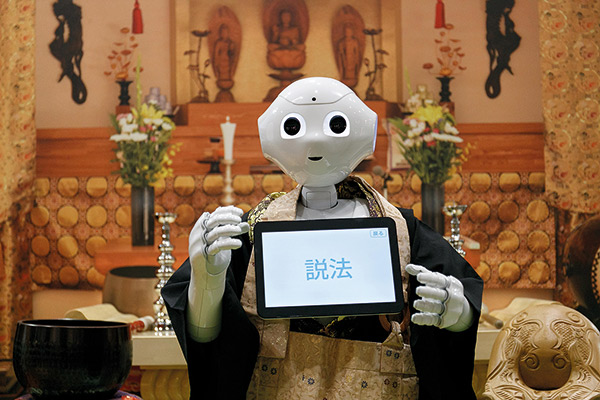

Some funeral homes in Japan use androids for chanting sutras over the deceased and livestreaming services to distant family members. Photograph from Aflo Co. Ltd. / Alamy. Used by permission.

Some have encouraged training LM-based chatbots on the Bible; others, while warm to the idea, have exhorted machine-learning practitioners to erect guardrails to ensure these LMs return text congruent with both the Bible and their users’ theological stances. As one such practitioner, let me say clearly: there is no way to guarantee this. Because LMs are not comprised of retrievable data and hand-coded interpretable rules, but rather abstracted statistical reflections of their training data, perfectly imposing such guardrails is an unsolved problem to which there may be no final answer. LMs do not look up information. That is not how they work. This makes LMs a fundamentally inappropriate tool for handling the Bible, where information retrieval accuracy and interpretive fidelity are nonnegotiable. Engineers know that building a bridge with the wrong material will cause it to fall down, and good engineers refuse to build bad bridges; let the reader understand.

Another temptation is to slip from using LMs to organize church content to using them to commodify that content. In our postpandemic era of broadcasting everything online, the tendency to turn acts of worship into acts of marketing is hard to resist, and sermons are a facile target for this trap. Outsourcing follows commodification, which could here result in an outright denial of the duty to preach. Some leaders in my own Episcopal Church are already situated at this dangerous pass, placing sermons in the same category as parish announcements – items whose automation will free up overladen clergy for, presumably, real pastoral work.

Karl Barth’s notion of preaching as an exposition of the Word of God is a helpful counterweight to these plans for LM-generated sermons. When a sermon is planned by a minister and proclaimed to the people through the mouth of the church, the Holy Ghost assists the delivery and makes it the very Word of God to the hearer. Not all denominations will agree on this semi-sacramental view of preaching, but all should agree that sampling from a next-word predictor is an inappropriate and unethical replacement for it. A pastor is responsible for the congregation’s spiritual formation, to which preaching is central; who could delegate this to a synthetic-text machine? Accidentally generated heresy is a technical failure; a pastor refusing to speak from the heart and preferring to generate the most probable word sequences for a sermon to the congregation in his care is a moral failure.

The final stop on this dubious trajectory is saddling LMs with the task of liturgical composition. Congregants at a Bavarian church that attempted this found the service trite and unsettling, some even refusing to join in saying the Lord’s Prayer. Their discomfort was well founded: this type of LM use encroaches on the unique vocation of humans within the whole creation’s worship of God and creates a liturgical absurdity that we feel in our gut.

All of creation expresses a cacophony of praise to its Creator. “One day telleth another” of God’s glory, says the psalmist, where “there is neither speech nor language; but their voices are heard among them” (Ps. 19:2–3). In Isaiah, we hear that “the mountains and the hills shall break forth before you into singing, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands” (Isa. 55:12). Yet God appoints one creature to collect all the noisy voices of creation and consolidate them into ordered expression: the human being, whom God endowed with the richest linguistic faculties. Language powers are integral to our being made in the image of God. Through them, we are able to rationally organize and sit in dominion over creation and cultivate it, enacting God’s goodness to it and bringing forth the harvest of its praises to offer them to God. “O all ye Works of the Lord, bless ye the Lord,” the Prayer Book canticle has us cry before enumerating these Works, from the lightning and clouds to the whales and all that move in the waters. “Praise him, and magnify him forever!”

Of all creation, the human is the priest, mediating between it and God, in part by the ordering power of language. This priesthood is of all believers, as language faculties are universally inherent in us in potentia (and in actuality, far beyond what we might think; indeed, deaf babies babble in a structured manner with their hands, and signed languages possess full phonological and syntactical systems).

When we shirk our duty to use our language faculties to worship God, the infraction is multiple: we not only fail to offer our own sacrifice of praise and reject God who would respond in goodness, but we also deprive all created things from joining their natural expressions of praise to ours. “He that to praise and laud thee doth refrain, / Doth not refrain unto himself alone,” warns George Herbert, “But robs a thousand who would praise thee fain, / And doth commit a world of sinne in one.” The poet has the obligation to sing; the poet also needs to sing for his own sake because his song, reaching out to God, changes him. Given this, the idea of liturgists handing their jobs to LMs is farcical, as laughable as a man whose daughter needs surgery sending a calculator to be operated on instead. We present a dumb machine in our place, hiding from God who hears us when we call and transforms us when we ask, and doing collateral damage to other creatures in our care.

Photograph by Valaurian Waller. Used by permission.

Christians must instead look to Jesus. The Word of God, coming from the mouth of the Most High, became flesh. He took on materiality and carried it to the right hand of the Father at his ascension. He is the great high priest who mediates between God and creation, through whom all creation will be redeemed on the last day. He shares our humanity, collecting the noisy and often incredibly sideways praises of our human life in himself and ordering them according to the divinity of the Logos – and he calls Christians to follow him in this. We, therefore, cannot abandon our role in orchestrating, via our own language, worship in which all creation participates. Outsourcing this to a text generator is absurd in the extreme, a near-literal abdication of the throne God set up for human beings, who, while made a little lower than the angels, have everything in subjection under their feet through Jesus, the eternal Word, true man yet very God.

Where does this leave the church? The fixation on LMs as content generators, tools that circumvent the necessity of thinking together, is symptomatic of a deeper disease, developing out of our failure to integrate our unprecedented technological interconnectedness with the bodily realities that true Christian – true human – interdependence demands. The church uncritically glomming onto the latest LM for its liturgical, educational, or pastoral work will compound the harm in this area already inflicted by the long, lonely slog of the pandemic.

There is no world where deferring preaching and pastoral care to a text generator does not end with deterioration – first of formation, then of the clergy, and finally of the people in their care. As more seminaries move online or shutter altogether, and more clerics are forced to work full-time jobs at part-time pay, what else can the replacement of their functions by LMs spell for those in pastoral need?

There is also no world where increased comfort with liturgical automation does not end with attempts to obviate the sacraments. Our Lord peskily attached himself to material things that force Christians to keep one foot in reality. But this tether is threatened, not by him but us, and not to his detriment but ours, if we go down the path of thinking that a machine can compose or recite a prayer to almighty God.

Meanwhile, captive to the view that sees LMs as content machines only, people who rightly object to this direction in the church will retrench, potentially causing a churchwide neglect of the opportunities to use machine learning well – opportunities less flashy but more helpful. Great promise exists for LMs in service of better research, the offloading of true drudgery, and increased access to various aspects of public and personal life for the linguistically barred – and indeed LMs have been fueling all these things without public fanfare or objection for many years. Opposition will be created in areas where none need exist.

A renewed belief in the communion of saints is a necessary part of the treatment. Saint Paul says that every member of this body is needed. All contribute something irreplaceable by anything else animate or inanimate, carbon or silicon. The incorporation of Christians as human persons into one body, that of the divine Word himself, is a profound mystery that cannot in fact be menaced or usurped by a text generator, try though we might through active promotion or doomsaying alike.

We should take heart in that, and then take up and read – and write, communicate, and contemplate, first enjoying and maintaining those gifts from God without fear of their replacement. Then, having received freely, we should freely give. Using language technology for the right purposes will facilitate the exercise of those gifts by those who would usually be restricted from their use by physical condition or temporal station. Neither slick demos nor technical party tricks can get us there. What is required is nothing less than a true love of God and neighbor, which no machine can generate.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Dusty Rubeck

This is an excellent analysis that helps to capture a theological framework for much of AI. Our churches and church leaders have probably not done enough thinking about a "theology of technology" to guide us in this current age. The old adage that technology is simply a "neutral tool that can be used for good or evil" seems shortsighted to me. Thank you for this thought-provoking analysis.

Timothy Davis

Thank you for this insight article! I thought of a couple of extensions while I read and discussed it with a friend (whose pastor is welcoming input on this topic from his elders): Leading by example: o Should a pastor be okay with ignoring or further marginalizing the actual artists in their congregation by not asking for creative help from people with those gifts? Further, should they avoid the harder issues related to having no or few artists in your church to begin with? o If the role of an elder is to "equip the saints for good works," and to find and call out the various spiritual gifts in the congregation, doing everything yourself avoids a large part of biblical instruction for pastors. o Using something with an ethically/legally questionable provenance (copyright infringement is fine?). The evidence is now sufficiently in to say that harvesting data without consent from creative folks is the primary basis for the existance of the LLMs and image-generators publically available. o Railing against “big tech” on some things (media bias, “cancel culture”), but then being fully part of the problem by adopting their most questionable methods as “necessary” - this does not show oneself to be in, but not of, the world. Problems for sermons, specifically: o “Summaries” of positions are possibly fine, but they will be about commonly-held beliefs, not about cohesive bodies of doctrine from particular traditions. Commonly-held beliefs about Jesus are often what you’re contesting against as a preacher, not the other way around. o Is it fine to phone something in? Not if your job is matching the word you’re bringing from Scripture to the known growth needs of your congregation. This would make me think that the pastor is simply lazy or unqualified, rather than efficient or smart. o Prose and poetry: Professional writers are now sometimes using ChatGPT to write what it thinks their next paragraph should be, then doing the opposite in every way, as the “next paragraph” from the bot is sure to be cliche-ridden drivel. If that's the approach someone would take at church, great! Drivel-detectors are needed; but not drivel-imitators, especially not for serious matters. o Defaults and hallucinations: Even if you spend time editing the output of a chatbot, there is a strong pull toward "the power of the default" as Kevin Kelly terms it. Since hallucinations are likely a formal - rather than fully fixable - problem for LLMs, the attention needed for editing outputs would likely start to be similar in scale to doing the work yourself in the first place. The appeal is in spending less time on a sermon, but still getting something as good or better than your own creative product. When all the necessary checks start to need to be put in place, including checks that involve further deepening of skill - something that takes time, effort, and acumen to develop (including skills the pastor didn't believe they had; an eye for good writing, for instance) - the efficiency benefits look much smaller.

Charles Sullivan

You posit the question incorrectly. It's not "Should ChatGPT write sermons?" Rather "Can we tell when it does?" Harried clergy runs out of time during the week. They get burned out. Or sick. Or spiritually depleted. Supply clergy may be unavailable at the last minute. Fresh, new approaches on interpreting Scripture can elude the most earnest soul at times. Reworking that incisive commentary on Romans, delivered two years prior, is not a palatable alternative. The temptation to fulfill the exhortation "the show must go on" will, for at least some shepherds, overwhelm their moral scruples. Congregants, awaken to the new reality. AI-generated sermons will eventually descend to a pulpit near you. Ironically sermons form a wonderfully rich training base for building a large language model (LLM) database, perhaps the best imaginable, given the volume, scholarship, and quality of the writing. There are millions of sermons floating around the internet, freely available and easy to upload. The Bible, Talmud, Koran, Bhagavad Gita and most every other book of faith is an easy upload as well. With LLM's capability of analyzing and regurgitating the wisdom and exhortations of countless pastors, priests, rabbis, imams, and spiritual teachers of every faith, it is certain some flocks, somewhere, will be fed their spiritual nourishment next weekend. The AI-abetted practitioner will find it blissfully easy to provide prompts that will lead to the quick generation of quality sermons, lessons, and teachings, ripe for minimal customizing and localizing. Jokes can be inserted. Reference can be made to something specific to the faith community being addressed. LLM's will accept any manner of assignment to create a moving, inspirational message, whether it is to be based upon a specific Bible verse, allegorical story, historical event, current event, or whatever the practitioner desires. The flock will be fed and inspired. Within a year or two, LLM-based machines will become so mellifluous, so compelling, so penetrating in reaching our hearts and minds that humans won't be able to tell the difference between machine-generated content and the organic variety. Virtually every creative industry -- art, entertainment, education -- is being overrun with AI-generated content right now. Why should faith be inviolate? "What hath God wrought?" Samuel Morse had his epiphany in 1844. Robert Oppenheimer in 1945. With a mere $20 per-month subscription to ChatGPI, any messenger can ascend to the mount in 2024.

Ed Barrett

Having not heard an AI generated homily, I can't comment, other than to say that almost anything might be an improvement. Having endured 10 years of sermons that are either intellectually an inch deep and a mile wide or mostly consist of rambling scoldings, I am up for most anything - preferably with a discernible beginning, middle and end. Ed Barrett

Joerg Fritsch

What I miss in this article about ChatGPT and other LLMs is a perspective of hope that human actions will eventually lead to a better future. By neglecting this perspective--the perspective of hope--Christians withdraw themselves from shaping the future of this world, leaving the visionary part to entrepreneurs and CEOs of tech companies. While the article is very accurate in describing the technical limitations and flaws that LLMs have today, it does not consider the importance of imagination and vision in overcoming the limits of the present technological realities and using technology to fix some “flaws” of this world. We can effectively use our imagination and the technologies we create with it to become the bright light that the Sermon on the Mount commands us to be, illustrating the beauty of God's kingdom. Matthew 5:14-16: "You are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden. Nor do they light a lamp and put it under a basket, but on a lampstand, and it gives light to all who are in the house. Let your light so shine before men, that they may see your good works and glorify your Father in heaven.” (New King James Version, Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1982). Let’s also consider Jeremiah 29:11, which says, "For I know the thoughts that I think toward you, says the Lord, thoughts of peace and not of evil, to give you a future and a hope.” (NJKV) This aligns with the hopeful perspective we should adopt towards AI, seeing it as a tool that can be used to manifest God's plans for a better future. Given this mandate, Christians and churches should be the first ones using AI/LLMs for the good of humanity. For example, LLMs could play a role in facilitating ecumenical dialogue between different Christian traditions. By providing translations and summaries of diverging theological literature and perspectives, LLMs can help mutual understanding, bridge gaps, and promote unity within the churches. Isn’t that an important task, given that Jesus’ last prayer was for unity among his followers (John 17:20-23)? And then there are the more down-to-earth benefits, such as better automated transcription, translation, and subtitling services that can help non-native speakers, the deaf, and the hard of hearing participate more fully in worship and community life. By embracing AI and LLMs, we will certainly not be replacing the human element in our churches and worship but enhancing our ability to live out our faith in innovative and more impactful ways. This reflects a hopeful and forward-looking theology that embraces technological advancements as tools for realizing the kingdom of God on earth.

Xenia Esche

Like anything man invents, it will be used for good and for evil, and sometimes its a long time before we know which side its use falls on for sure. Only God knows the ultimate end of our means. However, with regards to AI writing sermons: It should be simply intuitive as a minister of God to know that using AI to write a sermon isn't ok for a servant of God to do. God speaks into each new day and He speaks to his servants who are listening for Him. In order for a word from the Lord to be fresh and relevant a man, not a machine created by man, needs to be hearing directly from the Holy Spirit. Otherwise, what you are feeding your flock is processed food. Junk food. Unhealthy shelf stable dead food. Sheep need new fresh pasture once they have already grazed an area for so long. If a man of God is really a man of God and not a slothful servant he will prepare fresh food to feed the flock of God. Man was made in God's image. The Spirit of God gives life. No innovation of MEN can replace GOD. Ever. Discerning sheep will refuse to eat from this junk food. They will search for new pasture if it isn't provided. God's not dead. AI is only as good as its programming and it never is moved by the Holy Spirit. Only man can accomplish this. And it's a sacred privilege to be called to serve God's people. God does not consult with His creation before instructing it. Yet, man thinks his inventions should be consulted to instruct man? Does anyone see a problem here besides me? Information retrieval system does not equal a wonderful counselor who is all knowing and an ever merciful and loving creator. So, put that in your AI pipe(line) and smoke it....🤣

Bruce Hunt

Great thoughts here about where our Christian purposes can be assisted by AI, versus where they may become undermined. I might be a little more optimistic about AI's abilities to help people grow in their faith, as an aid in producing certain kinds of basic, formalized content. Even asking it, with proper oversight, to generate the structure and transcript of a church service seems okay to me, in theory. The biggest mistake they made with the experiment in Bavaria, I think, was letting it "face" the worshippers and preach the sermon. The problem is that AI will "preach" anything asked of it; it's just an instrument, an actor, for good or for evil. To offer it to a group seeking exemplary guidance in pious worship is really giving a snake to those that asked for a fish, a scorpion to those that asked for an egg.