Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Taming Tech in Community

-

Tech Cities of the Bible

-

Give Me a Place

-

Send Us Your Surplus

-

Masters of Our Tools

-

ChatGPT Goes to Church

-

Poem: “Blackberry Hush in Memory Lane”

-

Poem: “A Lindisfarne Cross”

-

Poem “Fingered Forgiveness”

-

God’s Grandeur: A Poetry Comic

-

Birding Can Change You

-

Disability in The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store

-

In Praise of Excess

-

A Church in Ukraine Spreads Hope in Wartime

-

Toward a Gift Economy

-

Readers Respond

-

Loving the University

-

Locals Know Best

-

A Word of Appreciation

-

Gerhard Lohfink: Champion of Community

-

When a Bruderhof Is Born

-

Peter Waldo, the First Protestant?

-

Humans Are Magnificent

-

Who Needs a Car?

-

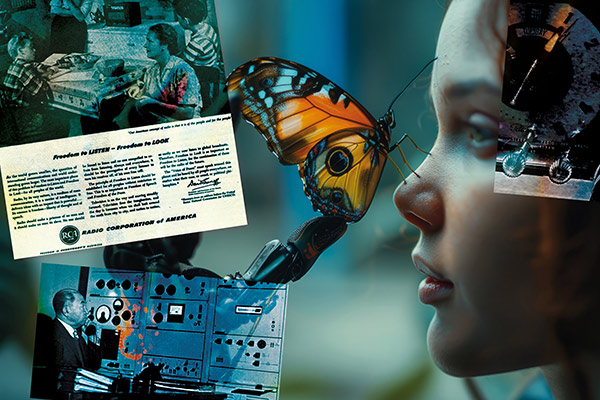

Covering the Cover: The Good of Tech

-

Jacques Ellul, Prophet of the Tech Age

-

It’s Getting Harder to Die

-

In Defense of Human Doctors

-

The Artificial Pancreas

-

From Scrolls to Scrolling in Synagogue

-

Computers Can’t Do Math

-

The Tech of Prison Parenting

Will There Be an AI Apocalypse?

Marshall McLuhan and Romano Guardini say it’s already here.

By Peter Berkman

June 28, 2024

Available languages: Deutsch

Elon Musk thinks the apocalypse is on the way. He’s not the only one. In the eyes of Silicon Valley’s leading experts on technology, an existential threat to civilization approaches: artificial intelligence. In their best-case scenario, AI heralds unprecedented mass unemployment. The worst: our machines get smart enough they don’t want us around anymore. Academics at some of the world’s top universities share Silicon Valley’s uncharacteristic discomfort with technological change: ethicists, philosophers, and historians have all weighed in at industry discussions on the impending catastrophe. Given the end-times rhetoric, it’s curious that religious thinkers have been left out of the conversation. Two neglected examples – Marshall McLuhan and Romano Guardini – might have especially pertinent contributions to make. Both men would have agreed with Silicon Valley that the scale and speed of technological progress could only appropriately be described as apocalyptic. But McLuhan and Guardini, despite never meeting in life, would have added the same qualification: the end of the world is already here.

McLuhan, a Canadian academic, died in 1980 at age sixty-nine, just as his trendsetting study of the information society, Understanding Media, which brought us terms like “the global village” and “the medium is the message,” was bringing him to the peak of his reluctant celebrity. He never met Guardini, an Italian-born German Catholic priest and theologian who died in 1968 at age eighty-three. Guardini’s ideas have quietly set the tone of Catholic thought for decades; every pope since the 1962–65 Second Vatican Council has cited his work as a major influence. McLuhan’s own influence, by way of contrast, has been confined largely to secular audiences, including Musk himself. McLuhan’s deep Christian faith pervades his writings, even if it barely enters into his reputation as one of the twentieth century’s major media theorists. Yet both McLuhan and Guardini, despite their very different backgrounds, looked at the new technological order unveiled in the aftermath of World War II and came to the same conclusion: the world – at least as they knew it – was ending.

Marshall McLuhan. Photography from WikiArt. Artwork from AdobeStock. Used by permission.

In fact, it already had. Guardini’s The End of the Modern World (1956) warned that we stood on the threshold of a new era in human history. “Something has come up that has not existed before,” Guardini told an audience of students at the time, “the unity of inhumanity and machine.” Something essential had taken place: the authority of the state converging with the power of technology. Human arts, once a means of security from natural dangers, had become the source of danger itself. In the optimistic atmosphere of postwar reconstruction, Guardini was a rare voice of alarm. This seemed a striking contrast to his prewar liturgical and spiritual writings. In the eyes of his critics – and many of his admirers – Guardini went from being ahead of the times to falling behind them. Even Guardini’s biographers tend to relegate this “melancholic” period to something like an emotional spasm, a footnote to his theological masterworks. There’s an element of truth in this. Guardini, who spent the interwar years mentoring young people, was persecuted by the Nazis in the 1930s and watched the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust unfold from a kind of internal exile. Yet as much as these events made Guardini disillusioned with modernity, his “melancholic” critiques of technological man nevertheless drew on his earliest work, just as McLuhan’s did.

In the 1925 book some consider his masterpiece, Der Gegensatz (opposition), Guardini resurrects the ancient and medieval theory, shared by Aristotle and Saint Thomas Aquinas, that there are two kinds of knowledge: a “sensible” knowledge akin to a sort of maternal instinct, and a “formal” knowledge that formulates everything for exact repetition. Like Aristotle and Aquinas before him, Guardini argues that “there is nothing in the intellect that was not first in the senses.” Intellect requires intuition; power requires ethics. One kind of knowledge presupposes the other. And the confusion of these two different forms of knowledge, he says, is the reason we so often uncover hidden biases in apparently “neutral” scientific thought. “The individual stands in a topsoil.” The more hidden the bias, the more aggressively it asserts itself.

In The End of the Modern World, Guardini looks back across the age of the Enlightenment and sees the gap between the scientific and the human widening to a chasm; what remains of civilization teeters on the edge of the abyss. In the order he saw emerging from the catastrophe of the war, Guardini discerned the contours of our contemporary dependence on technology. We have become physically all-powerful, Guardini warns, but our moral capacities have withered. Our reach outstrips our grasp.

We have become physically all-powerful, Guardini warns, but our moral capacities have withered. Our reach outstrips our grasp.

Our capacity to control the world around us has itself become uncontrollable, reducing both “divine sovereignty” and “human dignity” to words in a history book. “Contemporary man has not been trained to use power well,” Guardini writes, “nor has he – even in the loosest sense – an awareness of the problem itself.” Blind to the crisis our staggering technological capabilities represent, we conceive of everything in terms of power. But the remedy is more of the disease. “Again and again one is haunted by the fear,” Guardini concludes, “that to solve the flood of problems which threaten to engulf humanity … only violence will be used.” We have begun to revert to idol-worship, Guardini writes, “the worshipping of tools.” The “new culture” Guardini saw emerging in 1952 would be defined, above anything else, by a “single fact”: danger.

In the optimistic days of the immediate postwar era, Guardini’s darker vision of the future promised by scientific rationalism was far from common. It was one shared, however, by Marshall McLuhan. “I’m not an optimist or a pessimist,” McLuhan declared in an interview; “I’m an apocalyptic.” His first book, The Mechanical Bride (1951), was the culmination of a six-year project to understand the psychological weaponry of American advertising – and disarm it. McLuhan had clipped out hundreds of advertisements from newspapers, comics, and magazines and set them beside short essays, what he saw as a practical (if not moral) task of attempting to render the subconscious products of the culture business intelligible. Although McLuhan’s strategy was necessarily defensive, he was convinced opponents of new technologies of manipulation had to explore and understand their enemies, not simply retreat into denunciation. He suggested that the Americans trapped in the culture business adopt the attitude of the whirlpool-menaced sailor in Edgar Allen Poe’s “A Descent into the Maelström,” seeking “amusement in speculating upon the relative velocities of their several descents towards the foam below.”

As McLuhan told his interviewer, he wasn’t a pessimist about the world around him. But he wasn’t optimistic either. The “dominant pattern” of advertising, McLuhan wrote, was “composed of sex and technology,” eerily reminiscent of the future the nineteenth-century novelist Samuel Butler anticipated in his pioneering science fiction book Erewhon. “Machines were coming to resemble organisms,” McLuhan wrote of Butler’s fiction and our reality, and “people … were taking on the rigidity and thoughtless behaviorism of the machine.” This mechanistic worldview, which McLuhan called “know-how,” inculcated by humans’ ever-increasing use of machines with “powers so very much greater” than their own, was altering culture at every level. In the long term, he speculated, it threatened to make human life “obsolete.” In the present, it manifested itself in the victory of force over thought in the most immediate way imaginable: “murderous violence.”

Romano Guardini.

Like Guardini, McLuhan came to a new understanding of the contemporary world through his study of medieval thought. In his PhD thesis, written during the war and sent to the University of Cambridge chapter by chapter to avoid destruction by U-boat, McLuhan reread human learning in the Western world through the lens of what medieval thinkers considered the foundation of a good education, the “trivium” of grammar, dialectics, and rhetoric. The church baptized the classical ideal of the doctus orator, the learned speaker, interpreting structures through grammar, convincing others through words (rhetoric), and using dialectic as both an art for settling disputes and a means of intellectual speculation. Studying modern advertisers, McLuhan realized something key to his later work: intellectual progress isn’t unidirectional, but a pattern of repeats and retrievals, backward and forward across time. Advertisers in the 1950s were using the same methods of persuasion as thirteenth-century rhetoricians. But this technique was amputated from the rest of the arts: an instrument used without understanding, conveying countless effects without communicating ideas. And in a consumer society, this error determined the whole shape of our culture. The medium was the message.

Though working along different lines, McLuhan saw the problem of our age in similar terms to those of Guardini. Technology has given an untrained humanity unprecedented power over itself. At the same time, we have become numbed by this power, using it – or being used by it – without purpose or thought. Writing to Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain in 1969, McLuhan posed the resulting crisis in dramatic terms: “There is a deep-seated repugnance in the human breast against understanding the processes in which we are involved. Such understanding involves far too much responsibility for our actions.” He was echoing the thesis of another Guardini book, Power and Responsibility (1961): we have the first, but lack the second. As a result, our creations overpower and overcome us. Narcissus didn’t fall in love with himself, McLuhan warned, reinterpreting the ancient Greek fable. He fell in love, fatally, with an image of his own creation.

Similarly, for Guardini, the civilization of technique, all means without ends, threatens to erase the “essential values of nature and human work,” destroying reverence for the past – and for the person. Guardini’s “topsoil” had blown away. Herein, he writes, “lies the terribly new.” “Moral injustice,” “the spirit of violence,” “cruelty” all existed in the past. But the technological society, by “eliminating the personality of the human being,” dismissing all considerations other than those of raw power, “achieves something that is even more terrible than evil”: a system of thought and action with ethics left entirely out of the picture. In a strange way, both men understood the world in terms not entirely dissimilar to Musk and other contemporaries, who agonize over humankind being replaced by unfeeling robots or prophesy our enslavement to artificial, inhuman logics. Only for McLuhan and Guardini, this wasn’t a possible future, but a real present. The robots aren’t coming. To paraphrase Alasdair MacIntyre, they’ve been ruling us for some time.

What can we do? How do we escape the apocalypse? We can’t escape, McLuhan and Guardini would argue, and it’s pointless trying. There’s no way back. But there is a way through. Shortly after the publication of The Mechanical Bride, McLuhan carried out a research project comparing the effectiveness of learning by television, in person, over radio, and through the printed word. Assessing the results, television came out ahead and print at the bottom of the list. Advertising agencies circulated the results, McLuhan recalled, with the assertion that “here, at last, was scientific proof of the superiority of television.” The satellite was mightier than the pen. The advertisers’ reaction was “unfortunate,” McLuhan later wrote. They “missed the main point.” The study hadn’t indicated superiority, but difference, “differences so great they could be of kind rather than of degree.”

“The new mass media,” McLuhan writes, aren’t instruments, but contexts, “new languages, their grammars as yet unknown.” Each language in the “ecology” of telecommunication “codifies reality differently; each conceals a unique metaphysics.” None of these “languages” are neutral; each perpetuates particular sensitivities and particular blindnesses. “There is no harm in reminding ourselves that the ‘Prince of this World’ is a great PR man, a great salesman of new hardware and software, a great electrical engineer,” the master of an environment that is “invincibly persuasive when ignored.” Left unwatched, the reigning technological paradigm will inevitably provide our customs and habits for us. When the environment is invisible, the path of least resistance is determined by the medium itself. Our plans, as Guardini puts it, plan us. In order to recover human agency over technique, the invisible environment has to be made visible. “Apocalypse,” McLuhan says, “is our only hope.”

“The first Adam simply looked at things and labeled them.” So McLuhan observed in 1968. Christ, the second Adam, was a maker. Sharing in Christ’s inheritance means we have, McLuhan added, “the mandatory role of being creative,” and not passive. To survive the end of the modern world, we need to exhibit the capacity of artists to remake and reshape their surroundings – a faculty, McLuhan noted, which they share with saints. For Guardini, the antidote to an “autonomous technical-economic-political system” is the virtue of humility, which the medievals considered to consist, like most virtues, in a kind of balance. On one hand, we must admit that we do not have total control despite what inventions we may devise, without abnegating our God-given powers as human beings, namely those of understanding and action. “Jesus’ whole existence is a translation of power into humility. Or to state it actively: into obedience to the will of the Father as it expresses itself in the situation of each moment.” It is through self-renunciation – the acts Christians once described as “mortification,” dying a death to self, remaining aware of our human limitations in an inhuman, Promethean order – that we can see that order transformed. The sensors and satellites are not our enemies. They are us, the products of human intelligence, operated by human will, extensions of our powers and our frailties. And where sin abounds, grace also abounds. Christ calls us to let the light of God into the world – including the parts of it we ourselves have made.

McLuhan’s solution is consonant with Guardini’s. As a form of humility, we must admit that technology’s influences on our own perceptions are not immediately obvious. McLuhan saw his own research as a sustained effort to avoid self-deception: “study the modes of the media in order to hoick all assumptions out of the subliminal, non-verbal realm for scrutiny and for prediction and control of human purposes.” The goal is understanding. “What is the alternative to violence?” an audience member once asked McLuhan. He answered instantly: “Dialogue.” We can’t pierce the veil of the “hallucinogenic world” we exist within if we rely on “a reactionary romantic attitude,” rejecting science and technology to return to “a state of nature that could never be realized.” We can only do so in action, in the conscious and considered rejection of possibilities we might otherwise passively accept. “An ascetic is necessary, that is, a willingness to renounce technical achievements, so that higher values are maintained.” “It is not brains or intelligence that is needed,” McLuhan writes, but “a readiness to undervalue the world altogether.” Such a way of life, however, would appear as “anti-social behavior,” he warns. Making the invisible assumptions of our age visible might make Christians appear as odd as refusal to sacrifice to the gods once was. But it could also, he speculates, begin a “religious renaissance” in the world of the machine.

In 1959, speaking to the first-ever students to study computer science at Munich University, Guardini expressed a similar hope for the future. It was far too late to stop the change that was the end of the modern world, he thought, but it didn’t have to be a change for the worse. Moral agency could reassert itself over the technological order, in the life of individuals and of humanity as a whole. Guardini suggested a “spiritual council of the nations, in which the best from all political areas would consider these questions together.” He told the students that “it is time for a new virtue” to meet the challenge. “A living consciousness of humanity” could enable them to comprehend the “whole of our existence, with a truly sovereign objectivity.” A restoration of the lost “topsoil” of human life, a spiritual development on the scale of our scientific progress, an ethic to constrain and correct technique: this may sound like a utopia, Guardini granted. And in history, “the creative and unifying forces work more slowly than the one-sided violent ones.” Nevertheless, he maintained, utopias have often enough become reality. And all things are possible through God.

Pessimism about technology’s role in human life pervades our society as much as technology itself does: Silicon Valley’s contemporary fear of an AI-initiated cataclysm is a stark contrast to the arcadia the Valley’s founders imagined they’d create. But although McLuhan and Guardini counseled caution to the hopeful, they’d suggest realism in place of fear. Rather than rushing to find the right answers, they’d say we should try to find the right questions. There’s more to technology than what we perceive on the surface, good and bad. There’s more to human beings too. And it’s only when we understand the second that we can comprehend the first.

If McLuhan and Guardini were correct about technologies reshaping human sensibility, it seems fair to say that we are only at the beginning of the transition from an electric age to a digital age. It took centuries for medieval man to become modern man, and the shift from electric humanity to digital humanity is perhaps the most rapid and sweeping change we have ever undergone. Our response to this, as individuals and as a church, must be not to search for enemies – robotic or otherwise – but to look instead to the ways, old and new, that God is making himself known to us through the world he has made. The combined memorative power of all the world’s networked computers, equipped with hundreds of billions of sensors, with the interpretative power of code painstakingly laboring to make concrete all manner of human bias, as we live today, stands in literal comparison to six words uttered at a table in Jerusalem two thousand years ago: “Do this in memory of me.” Only one of these remains when the power goes out. Explaining why he called himself an apocalyptic, McLuhan noted that both optimism and pessimism are secular states of mind. “Apocalypse is not gloom,” he said. “It’s salvation.”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Miranda Haslem

I appreciate the way that Plough articles really stretch my mind with a relatively small amount of writing, in a phase of my life where I don’t have as much time to read as I would like, they are invaluable. Peter Berkman’s ‘Machine Apocalypse’ took me a while to digest and left me feeling challenged to keep attempting to unveil the realities under the surface of everyday life. As a youth worker it felt overwhelming to realise that the young people I work with have been born into a different ‘context / reality / metaphysics’ to me. And also that the need for them to be able to discern the mechanics of this reality, and find ways of developing an ethic to keep up with it's power will only increase with time. As always I can only find hope and ideas when I focus on the real people ‘in front of my face’ and what I am left with is the desire to create spaces where young people can become the artists and saints they already are by God’s design together, a prophecy collective. Also I love the idea of a ‘spiritual counsel of the nations’, but leaving initiatives like these to the adults has it’s pitfalls. I’m imagining a small group of young people eating takeaway Nandos and discussing ‘does technology change us from human beings into human doings?’