Subtotal: $

Checkout-

From Scrolls to Scrolling in Synagogue

-

Computers Can’t Do Math

-

The Tech of Prison Parenting

-

Will There Be an AI Apocalypse?

-

Taming Tech in Community

-

Tech Cities of the Bible

-

Give Me a Place

-

Send Us Your Surplus

-

Masters of Our Tools

-

ChatGPT Goes to Church

-

Poem: “Blackberry Hush in Memory Lane”

-

Poem: “A Lindisfarne Cross”

-

Poem “Fingered Forgiveness”

-

God’s Grandeur: A Poetry Comic

-

Birding Can Change You

-

Disability in The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store

-

In Praise of Excess

-

A Church in Ukraine Spreads Hope in Wartime

-

Toward a Gift Economy

-

Readers Respond

-

Loving the University

-

Locals Know Best

-

A Word of Appreciation

-

Gerhard Lohfink: Champion of Community

-

When a Bruderhof Is Born

-

Peter Waldo, the First Protestant?

-

Humans Are Magnificent

-

Who Needs a Car?

-

Covering the Cover: The Good of Tech

-

Jacques Ellul, Prophet of the Tech Age

-

It’s Getting Harder to Die

-

In Defense of Human Doctors

When I took my son and a bunch of his cousins swimming at the lake one afternoon last summer, I didn’t plan to lose a piece of someone’s pancreas. The boys were practicing flips off the dock. After an hour, their daring grew to the point that I called time. As they straggled onto the beach, I noticed that my nephew, whom I’ll call Tristan, was missing his smartphone, which he’d stuffed into a waterproof case. While the loss would be bad news for anyone, for Tristan it was far worse: the device is part of the management system for his type 1 diabetes, a condition in which the pancreas stops producing insulin. Until the 1920s, when scientists discovered how to extract insulin from dogs, type 1 diabetes was fatal in the short term. Even for decades afterward, a diagnosis meant a regimented life with daily glucose tests, exactly timed insulin injections, and a harshly restricted diet; despite all that, the disease still drastically reduced life expectancy and came with a high risk of side effects including blindness, heart and kidney failure, and limb loss.

Today, technology enables Tristan to live much like any other energetic twelve-year-old. Starting in 1978, scientists developed more sophisticated forms of insulin (synthetic, no dogs needed). In 1999, medical technology companies started producing continuous glucose monitoring systems (CGMs) that could track blood sugars using a probe placed under the skin. Then in 2017, easily portable CGMs became widely available. These give real-time readings on blood glucose levels. Today’s CGM talks via Bluetooth to a pump that delivers calibrated doses of insulin via a cannula. A cellphone controls the system and provides data to the user. This multi-component system is sometimes called an “artificial pancreas” for its ability to mimic the natural organ’s function.

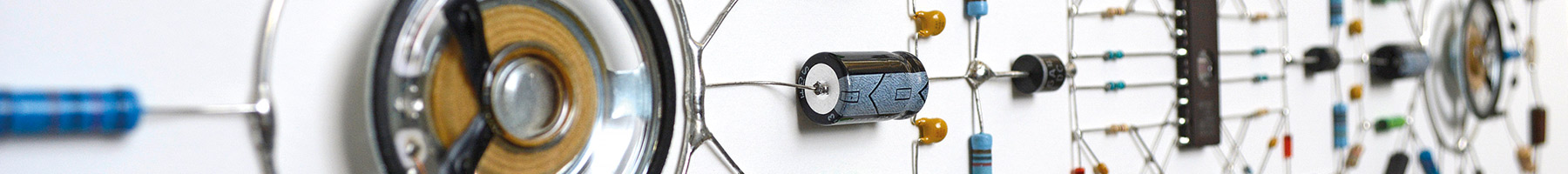

Leonard Ulian, Technological Mandala 83, electronic components, copper wire, and speakers on paper, 2015. All artwork used by permission,

It’s not the same as a natural pancreas, of course – the technology is glitchy and the human body is endlessly variable, so people with type 1 diabetes still struggle to maintain healthy glucose levels, knowing that high levels are unhealthy and lows can be life-threatening. Manual inputs are needed for every carbohydrate eaten, and both the sensor and pump need changing out every few days, making those affected not only dependent for their very lives on insulin but also, for good management, on the manufacturers of the cellphone, pump, CGM, and various other consumables. (That’s aside from the weird precarity and expense of insulin supply in the United States, where people with the condition regularly beg strangers for emergency doses on Reddit or die from attempts to ration their supply.) All the same, for someone with type 1 diabetes, this technology promises the chance at a greatly, if imperfectly, liberated life.

That is, until a piece of the system sinks to the bottom of a lake. From a check of Tristan’s wristband, it looked as if a cheap plastic clip had popped open when he swam to shore. This was a big deal: I knew from his parents that the system was new, having been finally approved by their health insurer, which, in addition, doesn’t cover the smartphone. For half an hour, we dove to search for the thing, but at a twelve-foot depth, the water was too murky to see much. All that remained was to hike home to confess to his parents, unsure what the loss meant. This time, luck was with us: they hadn’t thrown out the replaced older model yet. The artificial pancreas was soon working again, and we celebrated with glucose-heavy ice cream.

This is a happy story about the good of technology, the kind that can transform a kid’s life. It’s a technophile parable in which an artificial system that combines mobile software and automated hardware literally plugs into a human body, helping it to thrive in a way it wouldn’t if left to nature. The fact that such a technology exists in the first place is a testimony to the real achievements of Silicon Valley and its “Californian ideology,” which merged freewheeling innovation and entrepreneurial capitalism in a mission to change the world.

We seem to be on the cusp of a technological transition that may, once again, revolutionize our lives for good or ill.

In many quarters today, the promises of the Californian ideology have come to seem suspect. Contrary to the hopes of its early enthusiasts, the internet didn’t bring all of humanity together in the 1990s; neither did smartphone-enabled social media in the 2000s. In Washington, London, and Brussels, political leaders have long since stopped associating tech with utopian visions of global harmony, instead blaming it for distraction, polarization, addictions to porn and gambling, the trivialization of culture, loss of privacy and work-life balance, and fears that automation may push millions out of a job.

Growing skepticism has done little to stop the acceleration of change. Advances in artificial intelligence seem poised to bring us to the next technological watershed – very soon. That’s at least what AI’s cheerleaders promise, and its critics fear. “Generative” artificial general intelligence based on large language models – for example, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude, and Meta’s Llama – are rapidly increasing in power from version to version. Industry leaders such as Anthropic’s Dario Amodei believe that well-developed “agentic” AI may be just around the corner: that is, AI that can take actions in the real world, such as booking a vacation or planning a wedding.

Meanwhile, specialized versions of AI are transforming any number of industries. In pharmaceuticals, an AI breakthrough this year has solved a fifty-year-old problem of molecular biology by enabling scientists to quickly model the shape of proteins in three dimensions; other AI applications promise greatly accelerated drug development and testing. In healthcare, AI algorithms can detect cancers at early stages with high accuracy, often outperforming experienced radiologists. In retail, AI helps manage inventory and predict demand patterns, improving the efficiency of supply chains. And in the automotive industry, while fully autonomous vehicles still remain a future goal, AI systems in cars are already improving driver safety.

Leonardo Ulian, Technological Mandala 83, electronic components, copper wire, and speakers on paper, 2015.

Other developments are more unsettling. Several nations are already fine-tuning autonomous weapons systems – that is, killer robots – for use on the battlefield. In human genetic engineering, AI is accelerating genomics research, and so bringing forward the day when it will be possible to create designer babies. And then, of course, there’s the apocalypse: some AI experts worry that the technology could become powerful enough to cause human extinction, and the Pentagon seems to be taking seriously the risk that AI might somehow trigger nuclear war.

We seem to be on the cusp of a transition that may, once again, revolutionize our lives for good or ill. It’s a good time to ask how we should respond.

In 1992, just as the Californian ideology was picking up steam, Neil Postman published Technopoly, a classic work of cultural criticism that explores the relationship between humans and our tools. The book opens by quoting Plato’s account of the myth of Thamus, an Egyptian Pharaoh. The king is approached by the god Theuth, who presents various inventions, including writing. Theuth suggests that writing will improve both the wisdom and memory of the Egyptians. Thamus, however, objects:

This invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them. You have invented an elixir not of memory, but of reminding; and you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many things without instruction and will therefore seem to know many things, when they are for the most part ignorant and hard to get along with, since they are not wise, but only appear wise.

Reflecting on the myth, Postman observes that “every technology is both a burden and a blessing; not either-or, but this-and-that.” The very tool that promises to expand humans’ knowledge also robs them of their oral tradition. It makes new winners – adepts of the written word – and new losers: the elders who had been memory’s guardians. To update Postman’s telling, Theuth was setting in motion a chain of discoveries that would, in due course, transform words and images to digital tokens, and so give rise to ChatGPT.

Postman argues that digital technology, which reduces all meaning to symbols that a machine can compute, tends to change our view of nature and ourselves. We come to regard nature as mere information to be processed, and human beings as mere processors of that information. To the extent we allow the machine’s logic to become our own, we’ll become “tools of our tools,” in Thoreau’s phrase.

The real-life Postman practiced what he preached, eschewing digital tools such as word processors and cruise control. He chose to remain in an analog world that was vanishing as he wrote. In surveying the technological revolutions of the past, he’s always glancing wistfully backward. (This sometimes gives him blind spots; for example, he makes much of the flaws of modern medicine, while giving short shrift to its achievements.) He’s fascinated by the unpredictability of the effects of innovation, noting how the invention of the printing press by the pious Johannes Gutenberg had the unintended consequence of destroying the unity of Western Christendom. With each such shift, a world ends:

Technological change is neither additive nor subtractive. It is ecological. I mean “ecological” in the same sense as the word is used by environmental scientists. One significant change generates total change.… A new technology does not add or subtract something. It changes everything.

Just as introducing or eliminating one species can change a forest ecosystem, so a new technology can remake the whole fabric of our lives.

That’s the kind of ecological change that Jonathan Haidt chronicles in his new book, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. A social psychologist at New York University, Haidt compiles evidence of a surge in an array of ills that began around 2010, just when smartphones and Like-button-powered social media became part of childhood and adolescence. Over that period, he finds a spike among US teens in reported rates of anxiety, depression, and loneliness. Since 2010, suicide rates have risen 91 percent for American boys and 167 percent for girls, while emergency room visits for self-harm have risen 48 percent for boys and 188 percent for girls.

Provocatively, Haidt argues that this “surge of suffering” not only coincides with the advent of smartphones, but results from it. According to his findings, constant access to social media exacerbates girls’ image-consciousness and vulnerabilities, while internet-connected devices enable boys to retreat into virtual experiences to escape the challenges of the real world.

Some critics dispute Haidt’s interpretation of these trends. But practically, as a parent with three teenagers, I don’t have years to wait for scientific certainty, nor do other parents. We’re left with weighing up what evidence there is, and trusting our own eyes. It doesn’t take big data sets to see how rapidly and deeply childhood and adolescence have been transformed over the past decade and a half. But it does take a considerable amount of go-against-the-flow to act on what we see.

Leonardo Ulian, Techno Atlas 017(W) – Speak to Me, electronic components and copper wire on mdf and paper, 2022.

The impacts aren’t limited to mental illness rates. Consider the sheer amount of time kids spend on electronic media. In the early 1990s, US teens spent a little less than three hours a day looking at screens, mostly televisions. Today that number has gone up to six to eight hours a day, even more for those from low-income households (that’s just counting leisure time, not school-related use). There’s little mystery as to why. Multinational tech giants, armed with algorithms and vast amounts of data, have gotten ever better at keeping adolescents engaged with their products. That’s lucrative for them, but comes at a massive opportunity cost to kids, who are enticed to surrender vast chunks of their teenage days and years to screens.

It’s not enough, then, just to ask what teens are doing online, and whether some of it might be harmful. An equally important question is: what are all the things they aren’t doing offline? Drawing on Allie Conti’s reporting, Haidt tells the story of Luca, a young man from North Carolina:

Luca suffered from anxiety in middle school. His mother withdrew him when he was 12 and allowed him to study online from his bedroom. Boys of past generations who retreated to their bedrooms would have been confronted by boredom and almost unimaginable loneliness – conditions that would compel most homebound adolescents to change their ways or find help. Luca, however, found an online world just vivid enough to keep his mind from starving. Ten years later, he still plays video games and surfs the web all night. He sleeps all day.

Luca’s story is an extreme version of behavior that most parents of adolescent boys will recognize. As Postman would point out, it’s a playing-out of a dynamic that’s built into the technology, one that grows more powerful as the online experience becomes more immersive. Unless counterbalanced by offline interests, work, and friendships, the virtual world can swallow up a life.

Luca seems to be far from alone. There are substantial online communities for NEETs (“not in education, employment, or training”) and hikikomori, a Japanese term for young people who spend their lives as digital hermits in their bedrooms. One Reddit user explained when asked why he became a NEET: “Growing up I had zero friends and would just skip school to stay at home and play video games. Nothing much has changed now, except I dont go to school ofc.”

A strong communal culture can push back against pressure from technologies to shape humans in anti-human ways.

In Technopoly, Postman warns of the coming of a “totalitarian technocracy.” He seems to have meant an actual political takeover, in which tech elites control the rest of the population with powerful tools that secure their dominance. Thirty-two years after his book appeared, this dystopia has not materialized, despite the continuous exponential growth in computing power that has led to vastly more potent machines. Today’s tech moguls wield immense influence, yet are far more likely to face antitrust investigations than they are to seize dictatorial power.

While Technopoly focuses on society and systems, the deeper threat from technology today may be its effect on the individual soul. As virtual reality improves and AI chatbots grow more credible as friends and romantic partners, our tools are getting better at hacking our deepest human needs for love, purpose, and adventure. If we let them, they will offer us ever-more-convincing simulacra of what we desire, while holding us back – through distraction, habit, and lack of self-mastery – from experiencing the real thing.

But this isn’t as inevitable as Postman feared; we need not be at the mercy of our tools, nor despair of our capacity to control them. Clearly, it’s necessary to be mindful of the ways in which technology can shape us – of how (borrowing Marshall McLuhan’s famous phrase) the medium can become the message. But those maxims capture only part of the truth. It is equally true that human beings are free to use our creativity for good. So long as we do so, our species’ inventiveness is a feature, not a bug.

That’s most obviously true in the case of medical technologies such as Tristan’s CGM, which allows him to enjoy exactly the kind of “play-based” childhood that Haidt urges as the antidote to a “phone-based” one. A certain strain of conservative critique likes to draw the line between good and bad tech around medical uses, applauding progress in treating disease while seeing only the dangers of technical acceleration in other areas. Yet that tidy distinction breaks down in practice. After all, Tristan can practice risky flips at the lake thanks, in part, to the widespread availability of affordable smartphones, the very thing that drives the harmful trends Haidt highlights. The same large language model technologies that fuel worries about AI hold out the promise of even better treatments for future people with diabetes. We can’t get the good without running the risk of the bad.

How, then, can we live well with tech? For starters, by doubling down on the analog version of the very thing that tech products so often promise: community. Both Postman and Haidt, in different ways, help us to see that the challenge of tech is collective. Our response, too, must be collective; lonely acts of defiance, while often necessary, only get you so far. If, as seems likely, we’re facing another round of Postman’s “ecological” change, we must become all the more active in nurturing flesh-and-blood communities that are robust enough to keep technology in its place. That can be as simple as a network of parents setting common norms for their families. Or it can be a circle of friends, a school, a company, a church, or a commonwealth. Whatever the form, a strong communal culture can push back against pressure from technologies to shape humans in antihuman ways.

Leonardo Ulian, Technological Mandala 59 – 1+1=3, electronic components and copper wire on paper, 2015.

That’s what my own community, the Bruderhof, is trying to do on a small scale. We embrace forms of technology that we believe help foster the flourishing of individuals and our common life, while acting together to set boundaries on forms that do not. To take the specific example of tech’s impact on childhood, we practice a beefed-up interpretation of the guidelines that Haidt proposes in his book: Keep phones out of schools. Don’t give smartphones to kids until they’re at least old enough to drive (Tristan is the obvious exception here, but his older brother is still phone-free, and Tristan’s phone is stripped down to essential functions). Keep kids off social media until they’re old enough to vote, and in the case of adults, use it only when needed as a tool for work, study, or creative endeavors.

The same kind of boundary-setting is possible for society at large. In France, a panel commissioned by President Emmanuel Macron has recently proposed banning smartphones for kids under age thirteen and social media for kids under age fifteen. In regard to AI, even industry leaders agree on the need for more vigorous regulation than was typical in the early years of the internet and social media.

Communities with healthy cultures of solidarity matter then, at both micro and macro levels. Crucially, so do a community’s goals in using the technology it has. The Book of Genesis, though written in an ancient context, sheds light on this. According to its first chapters, humankind is created “in the image” of the Creator – endowed with creative ingenuity like that of God himself, and commissioned to act as his representatives in the world. God sets the first human beings over the rest of nature as its stewards and caretakers, commanding them to “fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the heavens and over every living thing that moves on the earth.”

After the first humans leave paradise, they set about doing just that, using their ingenuity to make tools, create structures, and develop organizations. When they use these technologies to build rightly, acting in fulfillment of their divine vocation, their work can end up saving both humankind and other species from catastrophe; that’s what Noah does in constructing the ark. But if they build in order to become independent of God, in violation of his commission to care for the world in his stead, their projects end in social breakdown. That’s what happens to the builders of the Tower of Babel.

How can we live out our vocation as stewards of creation in the way we use technology? There are quite practical ways. Drawing again on what my community has learned, we need not just disciplines and restrictions, but also (even more importantly) positive guides for living. Crowd out the virtual with the real; be present in the physical world. Give the bulk of your attention to the people who are near you in person. Spend time outdoors; watch sunsets and moonrises. Plant vegetables, go birdwatching or fishing or hunting. Raise puppies and rabbits and pigs.

A strong communal culture can push back against pressure from technologies to shape humans in anti-human ways.

Thamus was right; with each technological revolution, a world ends. But a world also begins. Theuth’s invention of writing brought the loss of oral traditions, while also making possible the composition of the Bible, not to mention the works of Plato, Dante, and Shakespeare. Seventy millennia ago, a world ended and another began with the invention of the bow and arrow; no doubt the same will happen again when the next technological frontier is broken.

That’s nothing to be afraid of, so long as we remember to proudly assert the freedom that belongs to humankind by right. We must remain the masters of our tools. For that, we need strong communities of the sort that many people around the world are striving to foster (some feature in this magazine). And we need to shape and use our tools in service of our human vocation, so that we can build, not Babels, but arks.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Jim Tung

Dear Mr. Mommsen: I very much enjoyed reading your article "The Artificial Pancreas" in the latest issue of Plough. It is fascinating to think about the good and the ill that technology can do. As a person* who works in the pharmaceutical manufacturing space, I do wish to make a comment about this passage in your essay: "In pharmaceuticals, an AI breakthrough this year has solved a fifty-year-old problem of molecular biology by enabling scientists to quickly model the shape of proteins in three dimensions" Your statement is not quite accurate; if it were up to me to edit this sentence, I would have struck "solved" for "advanced" and thought about adding the word "but not with 100% accuracy" to the "quickly" sentence. While Google AlphaFold is indeed a helpful advancement, I think most protein crystallographers view it has a helpful starting point and definitely not an end-all/be-all solution to structural biology. This point aside, I genuinely appreciated the essay and am pleased to be a Plough subscriber. Best wishes, Jim Tung *My credentials: I have a PhD in organic chemistry from the University of Notre Dame, and I have been working in and around the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry since 2007, and have done my best to keep current with advancements in the field. You probably have enough places to get your biomedical news, but Derek Lowe's blog In The Pipeline at Science Magazine is a great way to keep up with pharma, especially with Derek's very good writing style.

Larry Smith

Thank you, Peter, for this wonderfully balanced essay and for your thoughtful example — to which I would like to add one public policy recommendation: We would do well to drastically reduce or eliminate the ability of tech companies to use the free information and services they provide to profile and track us, then to monetize that information. Companies used to target us by fairly general parameters — gender, age, interests, etc. — and choose media that reached those demographics. So mothers were reached with soap operas, men with Sports Illustrated, businesspeople with the Wall Street Journal, and handymen with Popular Mechanics. We were targeted as members of groups. Now we are specifically targeted based on items we buy from Amazon, interests evident in our web surfing, images that appeal to us on Instagram, the range of our email contacts on gmail, our politics as revealed in our news sources — and we can then be reached individually by advertisers through those media and by direct solicitation. Our personal data, all that free content we consume, is monetized. What if those who offer all that free content were forbidden from retaining our individual data? What if our personal data remained our own? We would be required to pay for some valuable services; e.g., a Google or Facebook subscription. But how much fake news would remain if the eyes watching it could not be monetized? How many people would view Pornhub if they had to provide a credit card? Emphasis on community, as at the Bruderhof, is a beautiful lesson from which I/we can all learn, but as a defensive move it seems inadequate. The missiles of tech will keep finding their way to us and to our children and grandchildren because we incent them to do so. I fear that we are fighting a losing battle and need to cut off the aggressors at the source by depriving them of the personal data that fuels their attack.