Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Educating for Freedom

-

Why I Became a Firefighter

-

The School that Escaped to the Alps

-

Does Teaching Literature and Writing Have a Future?

-

Schools for Philosopher-Carpenters

-

Deerassic Park

-

Why We’re Failing to Pass on Christianity

-

For the Love of Public School Teaching

-

Let Children Play

-

The Music on Mount Sinai

-

The Green Paint Incident

-

Reverence for the Child

-

How Math Makes You a Better Person

-

Tell an Old Story for Modern Times

-

Should I Read Scary Fairy Tales to My Child?

-

Lernvergnügenstag: A Day for the Joy of Learning

-

Freedom of Speech Under Threat

-

Poem: “A Meditation on Figs”

-

Poem: “Hearing a Lecture on the Mandelbrot Set”

-

Poem: “On Raphael’s La Disputa del Sacramento”

-

We’re Alone Together

-

Disagreeing Respectfully

-

Life without Magic

-

The Jakob Hutter Story

-

Readers Respond

-

Free Care and Prayer

-

Our Home, Their Castle

-

Sister Penelope in Expectation

-

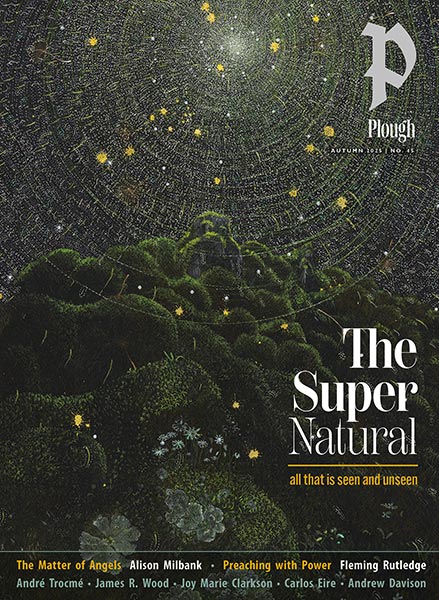

Covering the Cover: Educating Humans

-

The Most Valuable Joads

-

Timber Framing with Teenagers

-

Iron Sharpens Iron

-

Grand Canyon Classroom

The Homeschooling Option

Homeschooling in America has never been more widespread – or more diverse. We checked in on several parents in Detroit.

By Casey Kleczek

November 29, 2024

Available languages: Español

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

Nestled between two major trucking centers and highways 94 and 75 in southwest Detroit, Clayton Street is a flurry of urban chaos on weekday mornings. Trucks rumble off to work, frazzled commuters honk horns, a long line of cars creeps along at the public school drop-off, and raucous backpack-clad children fill the sidewalks. In the middle of this cacophony, on the dandelion-covered lawn of a century-old home, Danna Guzman and her students are also beginning their day. Sitting cross-legged in a circle, they discuss the week’s itinerary – a visit to the post office to learn about stamps, a lesson on film cameras with one of the children’s parents, fishing in the Detroit River, and their city council meeting. Several pick dandelions or study potato bugs while they listen, younger ones fidget, and one older child follows an infant crawling off to the sandbox. But in this corner of the world, where seemingly everyone around them is racing toward some quantitative end, they are a strikingly static anomaly.

The Big Bad Wolf House (as named by the students), a homeschool community born during the Covid pandemic, is a constant source of curiosity in the largely Mexican neighborhood. Some think what the school is doing is irresponsible, at best. Curious passersby peer over the fence, or roll down their windows as they drive by. Guzman is regularly answering the question, “Aren’t you afraid they won’t learn?” But her students continue to defy expectations – and fears – with each traditional benchmark met or surpassed. It’s clear to even the skeptics that something she is doing is working.

Traditional Roots

Danna Guzman didn’t grow up like this. Her parents, Mexican immigrants, were eager to ensure a solid education for her. “My educational path was very traditional,” she explains, “I think a lot of immigrants believe that education is the path toward the American dream. And so I took that path.” She went to a public school and excelled academically, eventually going on to get her bachelor’s degree in early childhood education and social work.

But despite her applicable degree, homeschooling was never part of her plan, even when she became the mother of three. It was born of necessity. When her oldest daughter reached school age it became clear that traditional schooling was not a good fit. “There was always a battle of trying to get out of the house, trying to get into the vehicle,” Guzman recalls. So she and her husband experimented, enrolling her in different types of schools – a Waldorf school, a Montessori, and others. “We tried all the pedagogical pathways.” The watershed moment came when their daughter tried to jump out of a moving vehicle on the way to school. When schools closed during the pandemic, it was an opportunity for Guzman to “test homeschooling.”

Jonathan Gladding, Two Children, Late Afternoon, Oil on canvas, 2021. Used by permission.

“We got into self-directed education,” explains Guzman, referring to an approach that is led by the students’ interests and curiosities as opposed to a defined curriculum. Once she and her children got in a rhythm, she opened up her doors to other families in the area and formed a pandemic pod of seven students. The pod grew as word about Danna Guzman’s unusual school spread through the neighborhood. What was initially a Band-Aid fix to hold them over during school closures became a compelling alternative to traditional school. So when schools reopened, the families wanted her to continue.

Guzman moved her family to a larger multifamily home surrounded by several empty lots she saw brimming with potential. Today, the Guzman family occupies the upstairs apartment while the main floor is for the Big Bad Wolf House. A formerly stuffy dining room is now the gathering space for lessons and arts and crafts, with a rotating series of finger paintings covering the walls. Bright plush rugs were laid on the hardwood floors to warm up the drafty space. Outside, students helped create a mud kitchen, build a sandbox, and plant a garden to combat pollution. Guzman’s parents moved in next door and put up a jungle gym. Some students’ parents have been working on a straw bale tunnel. In three years, the school has grown to sixteen students, with full-time and part-time options and summer camps. To the inquisitive neighbors peering over the fence, the school is a regular reminder that traditional education is not the only option.

New Trends

Far from an anomaly, Guzman’s story is part of a larger trend of parents pioneering homeschooling for their children. Today, homeschooling is the fastest-growing form of education in the United States by a wide margin. While the pandemic gave homeschooling rates a dramatic boost, the US Census Bureau’s household pulse survey shows that rates of homeschooling have remained well above pre-pandemic levels. Today over 5 percent of students are homeschooled (pre-pandemic it was 3 percent). The number of homeschooled students increased 51 percent over the past six school years, far outpacing the 7 percent growth in private school enrollment. Furthermore, it’s increasing across every social, political, geographical, and ethnic demographic. In 2022, 32 percent of homeschooling families in the United States were people of color. The rate of black families homeschooling kids increased by five times in 2020. What was formerly a fringe mode of education attributed to religious zealots or outliers has become a significant feature of the American educational system.

The modern homeschooling movement is, in part, the fruit of an unlikely friendship between educational theorists John Holt, a radical school reformer behind the unschooling movement of the 1970s, and Raymond Moore, a devout Christian who advocated delaying formal schooling. Together they advocated for families – both religious and secular – to leave the rigidity of traditional school systems and pursue child-centered curriculums by fighting legal battles and petitioning state legislatures to accommodate homeschoolers. The 1980s brought what one education historian calls, “the changing of the guard,” a new wave of homeschoolers, largely evangelical and fundamentalist Christians who saw homeschooling as a tool for educating their children in their fundamentalist theology and safeguarding them from other cultural worldviews.

But today’s families are pursuing homeschooling for a broad range of pedagogical and pragmatic reasons that have recently eclipsed religious concerns as the primary motivator. The National Household Education Survey Program found that 25 percent of parents cited concern about the school environment and 15 percent cited bad academic quality, with only 13 percent citing a desire to provide religious instruction. Other reasons included health problems, special needs, a desire to provide nontraditional education, and an emphasis on family. Parents who were forced to homeschool during the pandemic suddenly realized the feasibility of teaching from home, a choice they previously would never have considered.

Different Motivations

Growing up, Syreeta Faria knew about two educational options. “I didn’t know anybody who was homeschooled, I didn’t even know that was something people did. People either went to public school or private school. That was really all I knew about educational options.” When she got married and had two children, she went from working full-time to part-time so she could be home with her kids.

“But once they were old enough to go to school, my thought was, ‘You guys are going back to school and I’m going back to work, and we’re just going to do life as normal.’ I’ve got two degrees. Homeschooling was not a thought on my mind at all.”

When the time came to enroll her oldest in preschool, Faria did extensive research. She looked at licensing reports, references, and accreditation and did countless tours, before finding the school she felt really good about. But her daughter – not so much. What started as a couple of teary days turned into weeks and months, and finally, as Covid outbreaks continued to cancel school, Faria decided she would temporarily keep her daughter home, and they would “regroup when we get to kindergarten.”

The time at home was a wake-up call for her. Getting good marks on tests at school was one thing, but seeing the reality of your child’s progress at home was something that couldn’t be ignored. “I’m a black woman. I live in Detroit. Our schools don’t fare well on the academic indices that they use to rate public schools. I realized that what I wanted for my children academically was not what we were going to get from a traditional school.”

Syreeta Faria wasn’t the only one feeling this way. Many families in her neighborhood were unsettled by the quality of education their children were receiving. “Covid-19 was a wake-up call for black and brown families in Detroit, and an alarming one. A lot of parents started questioning the educational system, wondering why they were sending their children to a place for eight hours a day when they were still not doing well. A lot of parents started saying, ‘Fine, if nobody else can do this for my child, I can do this for my child. We’ll just leave and create what we need at home.’ Families in my community are getting very creative to try to figure that piece out.”

This motivated Faria to make her “temporary” decision to homeschool a permanent arrangement, but she didn’t want to do it alone. Two years ago, she formed a group, Detroit Discoverers, that meets once a week at the Detroit Public Library for story time, science experiments, group projects, and then field trips. It has eight families and sixteen students ages preschool through third grade, as well as a couple of tagalong siblings.

With the creation of her group, Faria has found herself in the position of regularly counseling parents who are considering homeschooling for their children. Many of the parents who come to her had never heard of homeschooling before Covid, and are daunted by the obligations.

“I just try to tell them not to be afraid to try what’s in their heart to do. It’s a big shift – I have moments myself where I wonder what I’m doing – but I think it’s like any other piece of parenting. As parents, especially as moms, we’ve taught our children so much already. We were the ones to read to them, talk to them, or sing to them. We were the ones to potty train them and introduce them to food. We’ve been educating our children their entire lives, and just as you were able to get them to figure out those challenges of getting them to eat peas or getting them to ride their bike, you can figure out the challenges of homeschooling them as well.”

A Desire for Community

A mother of two in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, Melissa Nichols started educating her two daughters at home after moving from California to Michigan and failing to find a school that welcomed the parental involvement she was used to. Her daughters’ old school in San Diego had been a small independent school with ample time outdoors, a large focus on the arts, and parents volunteering in the classroom. The new school her daughters attended, a public school in her area, hit her like a ton of bricks.

“All the doors are locked. You can’t go in. You can’t volunteer in the classroom. And you drop them off and pick them up at the door. I saw what her classroom looked like in August and I never saw it again. And I didn’t like that,” explains Nichols, “I really like being involved in my kids’ education. I think it’s such a big part of their lives.”

Much of what she was experiencing is the heightened school security as a response to school shootings. “A lot of schools have heightened security, which is good in a sense,” Nichols admits. “But then on the flip side, even the well-meaning parents and volunteers can’t get in. And we’ve lost the community experience of a school.”

She wasn’t finding a school that worked for her family, trapped between the choice of the expensive private schools in her area and the large public schools with “not much in between.” So she made a decision. With a background in teaching, she decided this would be the last school her children attended.

Her family swapped the frantic morning alarms and scarfing down breakfast for the hearty twelve hours of sleep she says her daughters need, and a languorous breakfast together as a family. The extracurriculars they once scrambled to pack into the few hours after school were now welcome diversions punctuating their leisurely afternoons. They hired a teacher to come to their home to teach their daughters academics for an hour – a fraction of the typical eight-hour school day – and enrolled them in virtual classes, a benefit from her job as the COO of a virtual prep school. The afternoons are reserved for forest school, Spanish group, baking, working on art, practicing piano, dance class, martial arts, and of course, play.

“We don’t need kids sitting at a desk for eight hours a day,” says Nichols. “There is so much more to life and living. I don’t want my kids to just live for summer breaks and holiday breaks. I want every day to count. I want every day to be intentional.”

In her ten years running operations for a private virtual school, she’s seen firsthand the damage that high-pressured environments and overscheduling have on kids. When families come to her virtual school, it’s often because they’ve been overextended and the child’s emotional well-being has plummeted.

“I feel like I see everyone around me rushing. Families are rushing through the week and living for the weekends. And we get to really enjoy ourselves every day. I love that I can walk out of my office for my lunch, go see my girls, and drive them to their different activities during the week. I think having ample time for playing and family is really important. One of the biggest reasons for homeschooling is just because I love spending time with my girls. I really can’t imagine at this point sending them off for the entire day. I feel like I know who they are as people because we spend a lot of time together. We’re really close as a family and it’s really special.”

In the years since her daughters started homeschooling, Melissa Nichols has started a homeschool group – Play and Fun Club – in an attempt to regain the community she felt she lost several years ago. “It’s an inclusive group. You can be religious or not. We just like coming together because we care about being intentional with our kids and homeschooling.” Nichols first proposed the idea in a Facebook group for her area several years ago. Since then, they have grown to twenty-five moms and over thirty kids. The social void she felt at a school her daughter was attending daily is now filled by this group. Once a week they don their bright yellow shirts with their logo (created by one of the moms) and head to a museum, garden, nature center, farm, or splash pad, or simply to one of their homes for a pool party.

“I now have fifteen close friends that all live locally,” Melissa gushes. The moms regularly get together without the kids for dinner, and they offer support, seek advice, or just vent in their very active text thread. Any impromptu park date is bound to turn up at least a couple moms and their children. Melissa finally feels like she’s raising her daughters the way she believes it’s supposed to be done – with a village.

“Aren’t You Afraid?”

Homeschooling’s growth hasn’t come without its detractors. Some see it as politically motivated – a way to undercut or weaken the influence of public schools and shield children from liberalism. Others have warned that homeschooling with lax regulation leaves kids vulnerable to abuse and neglect. But the critiques Danna Guzman, Syreeta Faria, and Melissa Nichols hear from people most are more about the ineffectuality of parents teaching their own children, or the recklessness of teaching children outside the established parameters.

“It can be really hard, especially in our era, to hold a space when everyone around you is saying school is the only way you’re going to be successful. A lot of folks in our community still believe that it’s illegal to homeschool,” Guzman explains. Even her parents had their doubts. “In the beginning, my mom was very nervous. And then my daughter learned how to read and then my mom was like, ‘OK, you know what you’re doing.’ She’s trusting me more and more.”

“Aren’t you afraid they won’t learn?” is probably the most common question she gets. But she continues to tell her friends and family, the curious neighbor idling on the street, or her Instagram followers that to educate we need to learn to trust children. “The best thing that we can do for children is believe that they can learn, and trust that they’re capable. Kids have always wanted to learn. Have you ever met one? They are eager to participate in their world! And the more they are able to contribute, to take responsibility for themselves and their learning, the harder it is to stop them!”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Joyce Laird

There's a new-ish phenomenon happening in groups with a religious identity: the hybrid homeschool. The children attend a physical campus a couple of times a week for a few hours. The rest of the time is spent at home. Specialist teachers in mathematics, sciences, etc are available at the physical campus. It gives the children an opportunity to work in social groups as well as at home. Here's an example of one of the hybrid schools. St. John Bosco Academy in Cumming GA and Shiloh GA is an example of a private hybrid school.