Subtotal: $

Checkout-

The School that Escaped to the Alps

-

Does Teaching Literature and Writing Have a Future?

-

Schools for Philosopher-Carpenters

-

Deerassic Park

-

Why We’re Failing to Pass on Christianity

-

For the Love of Public School Teaching

-

Let Children Play

-

The Music on Mount Sinai

-

The Green Paint Incident

-

Reverence for the Child

-

How Math Makes You a Better Person

-

Tell an Old Story for Modern Times

-

Should I Read Scary Fairy Tales to My Child?

-

Lernvergnügenstag: A Day for the Joy of Learning

-

Freedom of Speech Under Threat

-

Poem: “A Meditation on Figs”

-

Poem: “Hearing a Lecture on the Mandelbrot Set”

-

Poem: “On Raphael’s La Disputa del Sacramento”

-

We’re Alone Together

-

Disagreeing Respectfully

-

Life without Magic

-

The Jakob Hutter Story

-

Readers Respond

-

Free Care and Prayer

-

Our Home, Their Castle

-

Sister Penelope in Expectation

-

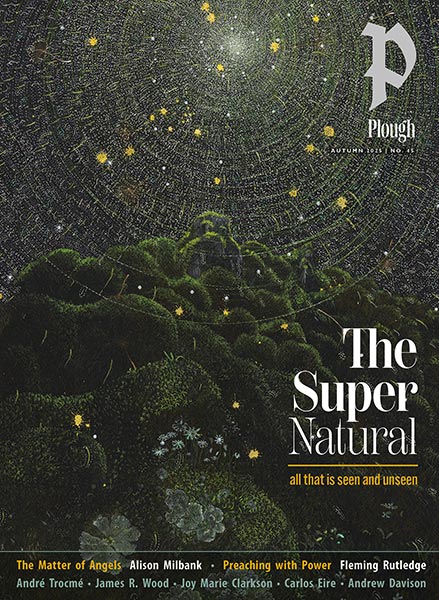

Covering the Cover: Educating Humans

-

The Most Valuable Joads

-

Timber Framing with Teenagers

-

Iron Sharpens Iron

-

Grand Canyon Classroom

-

The Homeschooling Option

-

Teaching the One Percent

-

Educating for Freedom

Why I Became a Firefighter

A priest joins her local volunteer fire department.

By Brit Frazier

December 5, 2024

Available languages: Deutsch

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

On an autumn evening in Sister Bay, Wisconsin, an instructor from the Northeast Wisconsin Technical College stands at the front of the multipurpose room of our village fire station. “You can probably survive third-degree burns,” he muses. “Maybe a fall. But not complete asphyxiation. In the event of flashover, you can try to jump out a window. But you could still die.” He pauses, looking at each of us. “Something to think about.” Our discussion about flashover – “a transition phase in the development of a compartment fire in which surfaces exposed to thermal radiation reach ignition temperature more or less simultaneously” – has mostly been a discussion about how to avoid death. This instructor is gifted in his matter-of-fact descriptions of potential catastrophe followed by a shrug and the invitation: “Something to think about.”

We’ve been given several somethings to think about by this point, about halfway through our state-mandated sixty hours of training to serve as volunteer firefighters. My class of fifteen students has assembled from the villages and unincorporated rural hamlets of Door County to make official what many of us have been doing for months or years as emergency response personnel. They’re local guys, mostly. A few maintenance workers, a mason, a painter, an electrician, a dairy farmer. And me, the only woman, a priest at the local Episcopal church. At thirty-five, I am about fifteen years older than the rest of the class.

The statistics vary slightly by origin, but the National Volunteer Fire Council affirms that of the over one million firefighters in the United States, more than 65 percent of us serve at departments staffed completely by volunteers. The “volunteer” designation is not always consistent from place to place. In general, we are paid: by call or by the hour, depending on the department, and departments maintain various levels of expectation regarding availability. Volunteer firefighters are trained to levels specified by state and local jurisdictions and to the guidelines of the National Fire Protection Association. These training levels are consistent with training for full-time career firefighters, though most volunteers work in other professions throughout their time of service. In recent years, news coverage regarding all departments – career, volunteer, and those with a mix of both – has been a litany of stories about shortage. Economic realities have resulted in fewer people who are able to step away from full-time jobs to respond to emergency calls. The necessity of multiple incomes to care for a family makes it notably harder for a spouse or parent to tend to additional obligations. When calls come in, there are fewer trained personnel with the ability to drop everything and show up.

The author (second from right) with other volunteeer firefighters. All photographs courtesy of the author.

It all started about a year ago, when I visited the fire station to inquire about an upcoming renewal course for my long-expired CPR certification. An officer was there, and he invited me inside.

“So you’re looking to do CPR?”

“Yes.”

“Are you in good health?”

“I think so?”

“Can you lift sixty pounds?”

“Yes,” I replied, guessing, but fairly certain.

“Would you like to become a firefighter?”

I assumed the department must have been desperate or fully committed to a half-comedic bit. But as the question crossed the officer’s desk, the picture emerged in my mind, fully formed and alive, with a clear sense of urgency and purpose. Suddenly it seemed to me to be the most natural thing in the world. Of course I wanted to be a firefighter. I was ready to begin at the very beginning.

That first day, the fire chief took my phone and entered the necessary credentials to secure my access to the app through which calls coming in to our department are dispatched. “When a call comes in, just come to the station,” he told me. I wasn’t convinced that he had heard me when I’d stated that I didn’t have any relevant experience at all. “Just come,” he assured me. “Just come to the station and do what we tell you. You’ll be fine.” My apprenticeship as a department probationer (“probie”) had begun.

Firefighter training in a rural volunteer department begins with instruction on the job. As a firefighter becomes more experienced, the individual may show capacity for leadership and be appointed an officer, and it is these more senior firefighters who shepherd the probies throughout the first awkward months of tagging along. It didn’t take much time for me to realize that even for a probie, I was behind. The young guys had grown up fixing propane tanks, building cars, and negotiating the other practical realities of rural life. I grew up in the suburbs, reading historical fiction and pretending to say Mass. When someone sent me to the toolbox to bring them a 5/16-inch nut driver, it wasn’t initially clear to me whether this was a tool or I was being hazed.

As with most things, information about firefighting comes from books, and wisdom comes from spending time with one’s feet on the ground. My first call came in on a summer afternoon as I sat alone in my parish office, polishing my Sunday sermon. I stared at my newly issued pager bleating and jumping around the desk as it vibrated with its summons. The dispatcher’s voice emerged: “Sister Bay Fire respond to …” with an address and a report of a runaway brushfire. Within moments, I’d locked the church and driven the three blocks over to the fire station, where a half dozen pickup trucks were heaving onto the back lawn. I pulled in behind them, unclear about precisely what came next. I didn’t have a locker. I didn’t have gear. Thanks to years of ministry, it was not the first time I’d been launched into something high-stakes and strange for which I had no previous experience or preparation. I ran into the apparatus bay and hollered at the first guy I saw: “I’m new! How can I help?” He wasted no time. “Get your shit and get on the truck.” With no shit to collect, I got on the truck.

One of the youngest firefighters tossed me a helmet, some extra pants, and a wildland firefighting shirt. I put them on as best I could, tucking the long pants into the tops of ill-fitting boots. It is often the case that eager volunteers come forward professing themselves fully committed to serving in the department, but far fewer stay on. A firefighter must stick around for a bit before the department will invest in personally sized gear just for you. The newest probies make do with borrowed gear – most of it decent, if not properly sized. This presents a considerable challenge if you, like me, are built more like an ice skater than an average-sized man.

We arrived on scene to find a sheepish-looking man in his sixties standing on the lawn with a pitifully spitting garden hose. Behind him, a half-acre of yard was burning, the flames jumping a crude perimeter fence and licking the lower two feet of a row of hedges. The spring season was dry this year, and a prohibited leaf burn had escalated quickly.

“Get the booster!” someone yelled behind me, and a firefighter began unraveling a long stretch of bright yellow one-inch fire hose from the side of the truck. I tried to help keep the hose from catching on obstructions in the yard. “What do I do now?” I asked one of the older officers standing nearby. He looked at me, not unkindly, and replied, “You put the fire out.” And so we did.

In July, we were called out to a search for a missing person, an older man with acute dementia. We searched throughout the night, running an ATV through corn fields and following canine tracking teams through the woods. Over eight hours into the search, a firefighter asked an officer, “When do we go home?” The officer snapped, “We go home when we’re done.”

It occurred to me that this was the first time it actually mattered if I stopped doing something. It was fifteen hours before we located the missing man, injured but stable, sleeping beneath an old bat trap and a pile of leaves.

Every week, the department gathers on Thursday evenings for a few hours of meetings and training. Topics vary by month: brush firefighting in July, ropes and technical rescue in August, medical emergencies in September, and so on. I dutifully show up every Thursday, exhilarated by my newfound usefulness, and a few months in, the chief asks if I’m interested in enrolling in the official firefighter training courses through the local technical college. I don’t tell him that I’ve had the dates on my calendar for months.

Our small northern station is lucky to have secured an instructor who will come all the way up the peninsula to lead the course. When I ask how much it will cost, I am informed that not only will the department pay for the program, we students will also be paid for every hour we spend in instruction: sixty hours of Entry-Level Firefighter, thirty more for our Firefighter I state certification, another twenty hours for Hazardous Materials Response and Operations. I wonder at why no one ever asked my seventeen-year-old novel-reading self whether she might like running into things that are on fire. I am grateful that my thirty-five-year-old self has not missed the chance.

Our lectures take place on Monday and Wednesday evenings from 6:30 p.m. to 9:30 p.m. We begin with some basic chemistry, the composition and behavior of fire, and the history of the fire service itself. Our 1,500-page textbook leads us through modules on fire attack, forcible entry, water supply systems, communications, search and rescue, personal protective equipment, and firefighter survival. On Saturdays, we depart the station at six in the morning to drive the hour and forty-five minutes down to the technical college campus in Green Bay. We learn to assemble and don our turnout gear and self-contained breathing apparatus in under two minutes. We run search and rescue drills in the three-story burn tower. The instructors light things on fire, and we work together to rescue dummies from smoke-filled bedrooms with walls that can be changed to surprise us from drill to drill. We put out car fires, we put out dumpster fires, we put out hay fires. One Saturday, we enter the flashover chamber, a trailer specially designed to permit firefighters to experience a fire as close to deadly as one can safely manipulate in training. We crawl into a pitch-black metal box, and the instructors light it up. Smoke descends from the ceiling, nearly to the ground, and when oxygen is introduced, the smoke layers explode with volcanic velocity. From somewhere in the haze, the instructor cackles, “Heh, heh, heh! You’re all my little biscuits in the oven!” One firefighter’s mask fills with smoke, and he dives headfirst out of the trailer. The rest of us press our faces to the floor.

In winter, fire departments in Wisconsin battle ice as often as fire. Snowstorms topple power lines onto trees and roofs, and the roads are slick with invisible ice. Motor vehicle accidents are called in with reliable regularity. The paramedics are mobilized too, but we often beat them to the scene. A truck crashes headlong into a tree in the early evening one Sunday in November, and within minutes, a team of four of us pulls out of the station in the rescue truck. We arrive on scene to find one female victim pinned against the steering wheel but responsive. The officer in charge deploys the massive hydraulic spreading tool to separate the door from the crushed vehicle. We gently ease her out of the truck and onto a cot, stabilizing her neck and shoulders against the fiberglass. The senior firefighters deal with the leaking diesel. I pick broken glass from the victim’s hair and hold her hand.

Later that weekend, the snow comes, unrelenting. Calls for downed trees and wires come so fast that we’re no longer receiving them from dispatch, but from our fellow firefighters in other apparatus at other scenes. “When you’re done at Woodcrest, head to Beach.” “When you’re done at Ridgeline, head to Green.” We pass cars in ditches along the way, stopping to assist as many as we can. The evening hours stretch into early morning, and our crew is sent to bring a generator to run an oxygen pump for a man without power. Just ten months ago, I knew almost nothing about the fire service, but now I know where the tools are. I know how to melt ice off the hose couplings using the exhaust pipe. I know how to chain tires and revive a frozen fire hydrant and pull a broken sump pump from a flooding basement.

I know how to laugh at two in the morning when the snow keeps coming and the 5/16-inch nut driver keeps falling out of our frozen hands. It occurs to me that this is how ministry would feel in a perfect world: high stakes, humble hearts, undergirded by an urgent mutual trust. We’ll go home when we’re done.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Nancy Piggott

Sounds remarkably similar to my years as a hospital chaplain. Facing reality calls for courage, compassion, humor and a transcendent love that is beyond human capacity.

DeVonna Allison

Ma’am, I tip my hat to you and thank you for being bold and inventive enough to enter into this newfound calling. You have my respect and your community’s gratitude.

Christa Von Zychlin

Beautiful, laugh out loud funny, and true. Thank you Mother Brit!