Subtotal: $

Checkout-

Tell an Old Story for Modern Times

-

Should I Read Scary Fairy Tales to My Child?

-

Lernvergnügenstag: A Day for the Joy of Learning

-

Freedom of Speech Under Threat

-

Poem: “A Meditation on Figs”

-

Poem: “Hearing a Lecture on the Mandelbrot Set”

-

Poem: “On Raphael’s La Disputa del Sacramento”

-

We’re Alone Together

-

Disagreeing Respectfully

-

Life without Magic

-

The Jakob Hutter Story

-

Readers Respond

-

Free Care and Prayer

-

Our Home, Their Castle

-

Sister Penelope in Expectation

-

Covering the Cover: Educating Humans

-

The Most Valuable Joads

-

Timber Framing with Teenagers

-

Iron Sharpens Iron

-

Grand Canyon Classroom

-

The Homeschooling Option

-

Teaching the One Percent

-

Educating for Freedom

-

Why I Became a Firefighter

-

The School that Escaped to the Alps

-

Does Teaching Literature and Writing Have a Future?

-

Schools for Philosopher-Carpenters

-

Deerassic Park

-

Why We’re Failing to Pass on Christianity

-

For the Love of Public School Teaching

-

Let Children Play

-

The Music on Mount Sinai

-

The Green Paint Incident

-

Reverence for the Child

How Math Makes You a Better Person

Across cultures, I found that math can be more than mere problem-solving.

By Frederick K. S. Leung

December 16, 2024

Next Article:

Explore Other Articles:

Professor Frederick K. S. Leung, president of the International Commission on Mathematical Instruction, speaks with Joy Clarkson, Plough’s books and culture editor, about math education and the subject’s connections with nature, truth, and beauty.

Plough: Your work has taken you all over the world to study how mathematics is taught. How does culture shape the way teachers teach and students learn mathematics? What influences success?

Frederick K. S. Leung: Many people consider mathematics to be a culturally neutral subject, and that whether or not a child learns it well depends only on the quality of classroom teaching and the talent of the child. But since the late 1980s, increased attention has been given to the sociocultural factors that influence the teaching and learning of the subject. Some scholars call this change in perspective the sociocultural turn in mathematics education. Then, in the mid-1990s, there were a number of international studies on student achievements that caught the attention of educators, policymakers, and the public. One surprising finding of these studies was that students in a cluster of East Asian countries and systems consistently performed very well in mathematics. These included Singapore, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, among others, all of which share what has come to be termed Confucian Heritage Culture.

This was when I, as someone who grew up in Chinese culture and yet received a basically Western education, started to utilize the lens of Confucian Heritage Culture in interpreting mathematics teaching, learning, and student achievement. In my research, I found that Confucian Heritage values such as a collectivistic orientation (in contrast to a Western individualistic one), an emphasis on the importance of education, attributions of success and failure, the place of effort and memorization in the learning process, and the image of the teacher as a reverenced scholar all have an impact on mathematics learning and achievement.

For example, one of my research projects involved observing classroom teaching in London and Beijing, and then interviewing teachers and parents. When I asked parents why their children struggled in mathematics, a typical answer from London parents was that their children were not gifted in mathematics – their children might do well in other spheres, but not in mathematics. In contrast, a common response from Beijing parents was that their children were lazy – if their children tried harder, they would have done better in mathematics. I find these different attributions of failure (and success) in mathematics intriguing.

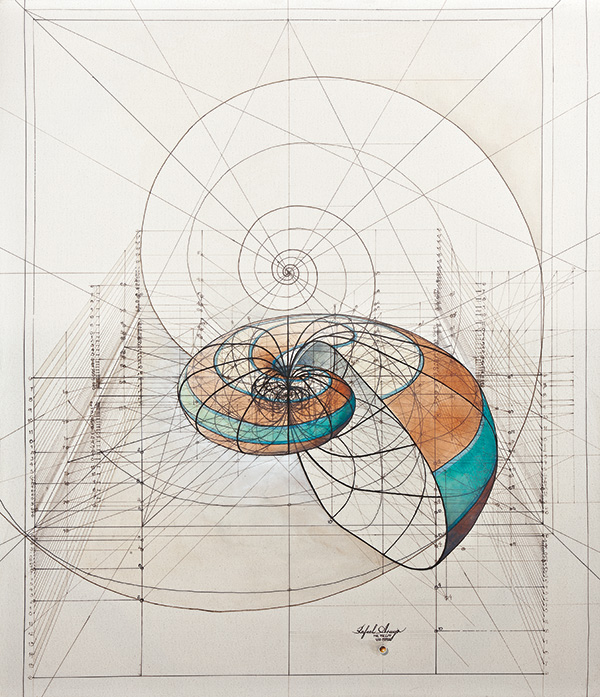

Rafael Araujo, Nautilus, ink and acrylic on canvas, 2011. Artwork by Rafael Araujo. Used by permission.

Cultural differences also influence the motivation to learn: in my research I found that many more students in the West were willing to learn mathematics because they found it interesting (we call this intrinsic motivation), but children brought up within a Confucian Heritage Culture were more likely to study hard in mathematics in order to get good grades, fulfill parental expectations, and bring honor to their family (extrinsic motivations). A mixture of both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation can help students thrive, and awareness of cultural differences can help teachers navigate this.

Why is math education important? How would you approach an unmotivated student?

Many people stress the instrumental value of mathematics and claim that it is a useful subject. But when you think about it, most of the mathematics that we learned in school seems rather useless – have you ever encountered a situation that required you to set up a quadratic equation in order to solve a problem? I am sure you learned quadratic equations in school, but you may have already forgotten what they are – and why do they matter, if you do not need to solve any real-life problems using quadratic equations anyway?

For me, the value of mathematics lies not in its usefulness in solving everyday problems, but in inculcating in students a sense of curiosity and in developing the capacity and habit of systematic, clear, precise, logical, and critical thinking. In this era of misinformation and fake news, this is all the more important. And being able to discern truth from falsehood is part of living a good life. Mathematics is about seeking truth, and being rigorous or truthful in the process. Of course, to achieve this, the teacher needs to teach mathematics in a way that instills these attributes, not treating mathematics merely as a skill to be imitated or a collection of facts to be memorized. The essence of mathematics lies in the process that fosters these attributes, rather than in the product such as algebra and geometry. It is in this sense that I consider mathematics the most useful and valuable subject (together with the subject of language, perhaps) in the school curriculum.

If you want to cultivate this outlook in a student, encourage her to look for mathematics around her. Look for mathematics in nature and in the manmade environment. Look for beautiful figures, look for regularities, patterns of shapes and numbers. Play games with her that involve mathematics and reasoning. Try to ignite her curiosity, encouraging her to explore where the patterns are and to ask why. Bring home the idea that mathematics does not just come from the textbook. Then maybe one day she will grow to love mathematics, even textbook mathematics!

How has your work in mathematics education influenced your life?

I’m a mathematics teacher but I also strive to be a good student of mathematics. I have learned that mathematics is about truth – seeking truth and sticking to the truth. Being a student of mathematics has shaped how I live my life, how I seek truth. When making decisions, I try not to be swayed by my emotions and predilections, but remind myself to stay objective and critical, always questioning my own assumptions and possible biases. Approaching mathematical truth is approaching truth in nature, and is similar to approaching truth in God. Mathematics has taught me to approach truth with scrupulousness and sincerity, in awe. As I grew to love math, I began to find it beautiful too.

As the hymn “For the Beauty of the Earth” puts it, life is not just about achievement in math, but the beauty manifested by “the beauty of the earth” and “the beauty of the skies.” Life is also about human relationships – kindness to one another, and the love of peace and justice and fairness; about “the joy of human love,” and “the love which, from our birth, over and around us lies.” Mathematics has taught me to be attuned to this truth and beauty hidden throughout creation. As Augustine puts it, “Look upon the heavens, the earth, and the sea, and at everything in them.… They have forms because they have numbers. Take the latter away from them and they will be nothing. What is the source of their existence, then, if not the source of the existence of numbers? After all, they have being precisely to the extent that they are full of numbers.”

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Try 3 months of unlimited access. Start your FREE TRIAL today. Cancel anytime.

Allan Long

Yes! I am not a natural at math. In college (engineering), I had to take a brute force approach to calculus and only made it through by sheer determination. Since then, I have grown an appreciation for the subtle beauty of math. Often in nature, the beauty is best viewed on a grand scale. I think that can also apply to math and seeing beauty in the order and infinite. Thanks for this unique and under appreciated discipline.